The Haçienda

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2023) |

| |

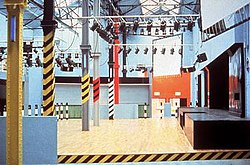

The Haçienda interior prior to opening | |

| Address | Whitworth Street West Manchester England |

|---|---|

| Owner | Factory Records New Order |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 21 May 1982 |

| Closed | 28 June 1997 |

| Demolished | 2002 |

| Architect | Ben Kelly (interior) |

The Haçienda was a nightclub and music venue in Manchester, England, which became famous during the Madchester years of the 1980s and early 1990s.[1][2][3][4] It was run by the record label Factory Records.

The club opened in 1982, eventually fostering the Manchester acid house and rave scene in the late 1980s. The early success of Factory band New Order, particularly with their 1983 dance hit "Blue Monday", helped to subsidise the club even as it lost considerable amounts of money (in part due to clubbers' embrace of the street drug ecstasy, which drove down traditional alcohol sales).

The club's subculture was noted by the Chief Constables of Merseyside and Greater Manchester as reducing football hooliganism. Crime and financial troubles plagued its later years, and it finally closed in 1997. It was subsequently demolished and replaced by apartments.

Creation

[edit]

The former warehouse occupied by the club was at 11–13 Whitworth Street West on the south side of the Rochdale Canal: the frontage was curved and built of red Accrington brick. Before it was turned into a club, the Haçienda was a yacht builder's shop and warehouse.[5]

It was conceived by Rob Gretton, and largely financed by the record label Factory Records, the band New Order, and label boss Tony Wilson. It was on the corner of Whitworth Street West and Albion Street, close to Castlefield, on the edge of the city centre. FAC 51 was its official designation in the Factory catalogue. New Order, Tony Wilson and Howard (Ginger) Jones were directors of the club.

Designed by Ben Kelly, upon recommendation by Factory graphic designer Peter Saville, upstairs consisted of a stage, dance area, bar, cloakroom, cafeteria area and balcony with a DJ booth. Downstairs was a cocktail bar called The Gay Traitor, which referred to Anthony Blunt, a British art historian who spied for the Soviet Union. The two other bars, The Kim Philby and Hicks, were named after Blunt's fellow spies. From 1995 onwards, the lower cellar areas of the venue were converted to create the 5th Man, a smaller music venue. Classics nights and private parties were held in the 5th man and local DJ Roy Baxter from Eccles was a resident warm up DJ handing over to the likes of Nipper and Jon Dasilva.

The sound and lighting design and installation for the Haçienda was done by Martin Disney Associates and later by Eddie Akka from Akwil Ltd.

Name

[edit]The name comes from a slogan of the radical group Situationist International: "The Hacienda Must Be Built", from Formulary for a New Urbanism by Ivan Chtcheglov.[6] A hacienda is a large homestead in a ranch or estate usually in places where Colonial Spanish culture has had architectural influence. Even though the cedilla is not used in Spanish, the spelling "Haçienda" was decided on for the club because the cedilla makes the "çi" resemble "51", the club's catalogue number.[7]

History

[edit]

The Haçienda was opened on 21 May 1982, when the comedian Bernard Manning remarked to the audience, "I've played some shit-holes during my time, but this is really something".[8] His jokes did not go down well with the crowd and he returned his fee.[9]

A wide range of musical acts appeared at the club. One of the earliest was the German EBM band Liaisons Dangereuses, which played there on 7 July 1982. The Smiths performed there three times in 1983. It served as a venue for Madonna on her first performance in the United Kingdom, where the renowned music photographer Kevin Cummins took photos of the evening on 27 January 1984.[10] She was invited to appear as part of a one-off, live television broadcast by Channel 4 music programme The Tube with then-resident Haçienda DJ Greg Wilson live mixing on the show.[11] Madonna performed "Holiday" whilst at the Haçienda and the performance was described by Norman Cook (better known as Fatboy Slim) as one that "mesmerised the crowd".[12]

At one time, the venue also included a hairdressing salon. As well as club nights there were regular concerts, including one in which Einstürzende Neubauten drilled into the walls that surrounded the stage.[6] The venue was instrumental in the careers of Happy Mondays, Oasis, the Stone Roses, 808 State, Chemical Brothers and Sub Sub.[13][14]

In 1986, it became one of the first British clubs to start playing house music, with DJs Hewan Clarke, Greg Wilson and later Mike Pickering (of Quando Quango and M People) and Little Martin (later with Graeme Park) hosting the visionary "Nude" night on Fridays. This night quickly became legendary, and helped to turn around the reputation and fortunes of the Haçienda, which went from making a consistent loss to being full every night of the week by early 1987.[15]

Acid house and rave

[edit]The growth of the 'Madchester' scene[16] had little to do with the healthy house music scene in Manchester at the time but it was boosted by the success of the Haçienda's pioneering Ibiza night, "Hot", an acid house night hosted by Pickering and Jon Dasilva in July 1988.

However, drug use became a problem.[17] On 14 July 1989, the UK's first ecstasy-related death occurred at the club; 16-year-old Clare Leighton collapsed and died after her boyfriend gave her an ecstasy tablet.[18] The police clampdown that followed was opposed by Manchester City Council, which argued that the club contributed to an "active use of the city centre core" in line with the government's policy of regenerating urban areas.[8] The resulting problems caused the club to close for a short period in early 1991,[19] before reopening with increased security later the same year.[20]

Haçienda DJs made regular and guest appearances on radio and TV shows like Granada TV's Juice, Sunset 102 and BBC Radio 1. Between 1994 and 1997 Hacienda FM was a weekly show on Manchester dance station Kiss 102.

Security was frequently a problem, particularly in the club's latter years. There were several shootings inside and outside the club, and relations with the police and licensing authorities became troubled. When local magistrates and police visited the club in 1997, they witnessed a near-fatal assault on a man in the streets outside when 18-year-old Andrew Delahunty was hit over the head from behind with what looked like a metal bar before being pushed into the path of an oncoming car.[21]

Although security failures at the club were one of the contributing factors to the club eventually closing, the most likely cause was its finances. The club simply did not make enough money from the sale of alcohol, and this was mainly because many patrons instead turned to drug use. As a result, the club rarely broke even as alcohol sales are the main source of income for nightclubs.[22] Ultimately, the club's long-term future was crippled and, with spiralling debts, the Haçienda eventually closed definitively in the summer of 1997. Peter Hook stated in 2009 that the Haçienda lost up to £18 million in its latter years.[23]

Legacy

[edit]The Haçienda lost its entertainments licence in June 1997. The last night of the club was 28 June 1997, a club night called "Freak" featuring Elliot Eastwick and Dave Haslam[24] (the final live performance was by Spiritualized on 15 June 1997). The club remained open for a short period as an art gallery before finally going bankrupt and closing for good. After the Haçienda officially closed, it was used as a venue for two free parties organised by the Manchester free party scene. One of the parties ended in a police siege of the building while the party continued inside. These parties resulted in considerable damage and the application of graffiti to the Ben Kelly-designed interior.

Following a number of years standing empty, the Whitworth Street West site was purchased from the receivers by Crosby Homes. They chose to demolish the nightclub, and reuse the site for the construction of apartments. The old name was kept for the new development, with the Haçienda name licensed from Peter Hook, who owns the name and trademark. The nightclub was demolished in 2002—Crosby Homes had acquired the property some time before that and, on 25 November 2000, had held a charity auction of the various fixtures and fittings from the nightclub. Clubgoers and enthusiasts from across the country attended to buy memorabilia ranging from the DJ booth box and radiators to emergency exit lights.[25] The DJ booth was bought by Bobby Langley, ex-Haçienda DJ and Head of Merchandise for Sony Music London for an undisclosed fee.[26]

Crosby Homes were widely criticised for using the Haçienda brand name—and featuring the strapline "Now the party's over...you can come home" in the promotional material. Another controversial feature of the branding campaign was the appropriation of many of the themes which ran through the original building. One of these was the yellow and black hazard stripe motif which was a powerful element in the club's original design, featuring as it did on the club's dominant supporting pillars and later in much of the club's literature and flyers.[27]

Michael Winterbottom's 2002 film 24 Hour Party People starring Steve Coogan as Tony Wilson, tells the story of the Haçienda. The film was shot in 2001, and required reconstructing the Haçienda as a temporary set in a Manchester factory, which was then opened to ticket holders for a night, acting as a full-scale nightclub (except with free bar) as the film shooting took place.[28][29]

The Manchester exhibition centre Urbis hosted an exhibition celebrating the 25th anniversary of the club's opening, which ran from mid-July 2007 until mid-February 2008. Peter Hook and many other of those originally involved contributed or loaned material.[30][31]

The Manchester Museum of Science and Industry now holds a variety of Haçienda and Factory Records artefacts, including the main loading bay doors from the club, and a wide array of posters, fliers and props. Rob Gretton bequeathed his collection of Haçienda memorabilia to the museum.[32]

In October 2009, Peter Hook published his book on his time as co-owner of the Haçienda, How Not to Run a Club. In 2010, Peter Hook had six bass guitars made using wood from the Haçienda's dancefloor.[33][34] The fretboards have been made from dance floor planks, so they have "stiletto marks and cigarette burns".[35]

See also

[edit]- Freaky Dancing, a 1989–1990 fanzine, by Paul 'Fish Kid' Gill and Ste Pickford

- List of electronic dance music venues

References

[edit]- ^ "Legendary Hacienda Club comes to a close" Archived 22 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine, CNN, 8 January 2001

- ^ "Obituary: Tony Wilson", BBC News,10 August 2007

- ^ "UrbanPlanet - Legendary Nightclubs from Days Gone By". 20 February 2012. Archived from the original on 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Hacienda exhibit at D-mop", hongkonghustle.com. 7 October 2007.

- ^ Ahmed, Aneesa (30 May 2022). "The Haçienda was nearly in a warehouse in Castlefield, according to co-founder". Mixmag. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ a b 25 Year Party Palace. BBC. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- ^ "24 Hour Party People". Partypeoplemovie.com. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ a b Glinert, Ed (2008). The Manchester Compendium: A Street-by-Street History of England's Greatest Industrial City. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-102930-6.

- ^ Brewster, Bill; Broughton, Frank (2000). Last night a dj saved my life: the history of the disc jockey. Grove Press. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-8021-3688-6.

- ^ "Kevin Cummins on Manchester music". The Guardian. 19 September 2009. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ Donohue, Simon. Madonna Forgets Haçienda Visit". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- ^ Tim de Lisle (23 November 2005). "She mesmerised the crowd – you could just tell there was a personality there". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ^ "The biggest clubs we've loved and lost - from Fabric and Gatecrasher to the Hacienda". Bbc.co.uk. 7 September 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ Haslam, Dave (19 May 2017). "10 tracks the club built: How the Hacienda inspired an era of dance music". The Vinyl Factory. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ Bourne, Dianne (21 May 2022). "Hacienda at 40 - the highs, lows and £6m losses behind 'greatest club on earth'". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "The Hacienda, Acid House and Madchester | Peter J Walsh". British Culture Archive. 28 November 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ Connors, Rachael (27 July 2015). "Paul Massey death: Who was Salford's Mr Big?". BBC News Online. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ Collin, Matthew; Godfrey, John (1998). Altered state: the story of ecstasy culture and Acid House (2nd ed.). Serpent's Tail. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-85242-604-0.

- ^ Sutcliffe, Phil (5 March 1991). "Stories". Q Magazine. 55: 10.

- ^ Harking back to the Haçienda. BBC News. 6 November 2000.

- ^ "Gangchester", Mixmag, February 1998

- ^ The Hacienda: How Not to Run a Club, p. 158

- ^ "Peter Hook: 'Hacienda lost £18m'". BBC News. 2 October 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ Heward, Emily (28 June 2017). "The Haçienda closed 20 years ago today...here's what it looked like". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ Ward, David (29 August 2002). "Hacienda fans rave at plan for luxury flats". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ Bueno, Claire (26 May 2019). "Do You Own The Dancefloor? Everyman Q&A – PremiereScene.net". Premiere Scene. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ Stuart Aitken (March 2004). "Making a hash of the Haç". mad.co.uk.

- ^ NME (4 March 2001). "24 HOUR PARTY PEOPLE". NME. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ Hoad, Phil (6 February 2023). "'I did my climactic speech – then took half an E': Steve Coogan on making 24 Hour Party People". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "Fac and fiction". Manchester Evening News. 29 August 2007. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "Haçienda 25 The Exhibition: fac 491". The Urbis Archive. 14 January 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ Heward, Emily (14 January 2020). "Unseen Joy Division treasures to feature in new Factory Records exhibition". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "FAC 51 The Hacienda Limited Edition Peter Hook Bass Guitar". Archived from the original on 25 December 2016.

- ^ Ben Turner (12 January 2013). "Peter Hook's gig with bass guitar made from Hacienda floor". manchestereveningnews.

- ^ Rick Bowen (13 June 2013). "Altrincham shop lands rare guitar". messengernewspapers.co.uk.

Bibliography

[edit]- Savage, J. (1992). The Haçienda Must Be Built. International Music Publications. ISBN 0-86359-857-9.

- Wilson, Tony (2002). 24 Hour Party People. Pan MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-7522-2025-3.

- Hook, Peter (2009). The Hacienda: How Not to Run a Club. Simon & Schuster Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84737-135-5.

External links

[edit] Media related to The Haçienda at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Haçienda at Wikimedia Commons- The Haçienda discography at Discogs

- Pride Of Manchester Haçienda memories by Haçienda DJ Dave Haslam

- Haçienda Profile - Profile on the club & more on rave

- Ben Kelly Design - gallery of interior photos of The Haçienda Archived 8 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Fantazia.org.uk - Fantazia/Haçienda flyer from 1992

- The Haçienda Story Archived 8 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- The first Hacienda DJ Booth

- Hacienda DJ Booth Story

53°28′27.55″N 02°14′51.66″W / 53.4743194°N 2.2476833°W

- Nightclubs in Manchester

- Defunct nightclubs in the United Kingdom

- Demolished buildings and structures in Manchester

- History of Manchester

- Madchester

- Music venues in Manchester

- Electronic dance music venues

- Factory Records

- Music venues completed in 1982

- 1982 establishments in England

- 1997 disestablishments in England

- Warehouses in England

- Buildings and structures demolished in 2002