Ducking stool

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

Ducking stools or cucking stools were chairs formerly used for punishment of disorderly women, scolds, and dishonest tradesmen in medieval Europe[1] and elsewhere at later times.[2] The ducking-stool was a form of wymen pine, or "women's punishment", as referred to in Langland's Piers Plowman (1378). They were instruments of public humiliation and censure both primarily for the offense of scolding or backbiting and less often for sexual offences like bearing an illegitimate child or prostitution.

The stools were technical devices which formed part of the wider method of law enforcement through social humiliation. A common alternative was a court order to recite one's crimes or sins after Mass or in the market place on market day or informal action such as a Skimmington ride. They were usually of local manufacture with no standard design. Most were simply chairs into which the offender could be tied and exposed at her door or the site of her offence. Some were on wheels like a tumbrel that could be dragged around the parish. Some were put on poles so that they could be plunged into water, hence "ducking" stool. Stocks or pillories were similarly used for the punishment of men or women by humiliation.

The term "cucking-stool" is older, with written records dating back to the 13th and 14th centuries. Written records for the name "ducking stool" appear from 1597, and a statement in 1769 relates that "ducking-stool" is a corruption of the term "cucking-stool".[3] Whereas a cucking-stool could be and was used for humiliation with or without dunking the person in water, the name "ducking-stool" came to be used more specifically for those cucking-stools on an oscillating plank which were used to duck the person into water.[4]

Cucking-stools

[edit]A ballad, dating from about 1615, called "The Cucking of a Scold", illustrates the punishment inflicted to women whose behaviour made them be identified as "a Scold":

Then was the Scold herself,

In a wheelbarrow brought,

Stripped naked to the smock,

As in that case she ought:

Neats tongues about her neck

Were hung in open show;

And thus unto the cucking stool

This famous scold did go.[5]

The cucking-stool, or Stool of Repentance, has a long history, and was used by the Saxons, who called it the scealding or scolding stool. It is mentioned in Domesday Book as being in use at Chester, being called cathedra stercoris, a name which seems to confirm the first of the derivations suggested in the footnote below. Tied to this stool the woman—her head and feet bare—was publicly exposed at her door or paraded through the streets amidst the jeers of the crowd.[6]

The term cucking-stool is known to have been in use from about 1215. It means literally "defecation chair", as its name is derived from the old verb cukken and has not quite been rid of in many parts of the English speaking world as "to cack" (defecate) (akin to Dutch kakken and Latin cacāre [same meaning]; cf. Greek κακός/κακή ["bad/evil, vile, ugly, worthless"]), rather than, as popularly believed, from the word cuckold.[citation needed]

Both seem to have become more common in the second half of the sixteenth century. It has been suggested this reflected developing strains in gender relations, but it may simply be a result of the differential survival of records. The cucking-stool appears to have still been in use as late as the mid-18th century, with Poor Robin's Almanack of 1746 observing:

Now, if one cucking-stool was for each scold,

Some towns, I fear, would not their numbers hold.

Ducking-stools

[edit]

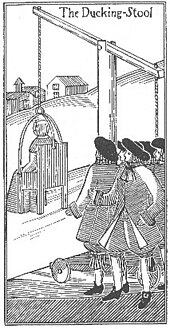

The ducking-stool was a strongly-made wooden armchair (the surviving specimens are of oak) in which the offender was seated, an iron band being placed around them so that they should not fall out during their immersion. The earliest record of the use of such is towards the beginning of the 17th century,[6] with the term being first attested in English in 1597. It was used both in Europe and in the English colonies of North America.[7]

Usually, the chair was fastened to a long wooden beam fixed as a seesaw on the edge of a pond or river. Sometimes, however, the ducking-stool was not a fixture but was mounted on a pair of wooden wheels so that it could be wheeled through the streets, and at the river-edge was hung by a chain from the end of a beam. In sentencing a woman the magistrates ordered the number of duckings she should have. Yet another type of ducking-stool was called a tumbrel. It was a chair on two wheels with two long shafts fixed to the axles. This was pushed into the pond and then the shafts released, thus tipping the chair up backwards. Sometimes the punishment proved fatal and the subject died.[6]

Use in identifying witches

[edit]In medieval times until the early 18th century, ducking was a way used to establish whether a suspect was a witch.[8] The ducking stools were first used for this purpose but ducking was later inflicted without the chair. In this instance the subject's right thumb was bound to her left big toe. A rope was tied around the waist of the accused and she was thrown into a river or deep pond. If she floated, it was deemed that she was in league with the devil, rejecting the baptismal water. If she sank, she was "cleared. And dead".[9][better source needed]

Notable examples

[edit]Surviving examples

[edit]The tumbrel of a ducking stool is in the crypt of the Collegiate Church of St Mary, Warwick. There is also a ducking chair in Canterbury, where the High Street meets the River Stour.[10]

A surviving ducking stool is on public display outside the Criminal Museum (Kriminalmuseum)[11] in Rothenburg ob der Tauber, a well-preserved medieval town in Bavaria, Germany.

Replicas

[edit]

A complete ducking stool is on public display in Leominster Priory, Herefordshire. The town clock, commissioned for the Millennium, features a moving ducking stool depiction.[citation needed]

Christchurch, Dorset, continues to house a replica ducking stool, at the site where punishments were once carried out.[12]

Early mentions

[edit]There is a reference from about 1378 to a ducking stool as wymen pine ("women's punishment"),[13]

In film

[edit]A type of ducking stool can be seen briefly in the film Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975).

In the 1944 Powell and Pressburger film A Canterbury Tale, an American soldier stopping over at the town hall in fictional Chillingbourne (a village near Canterbury), is puzzled by an antique piece of furniture that he spots; the local magistrate informs him that it is a ducking stool.

In the Laurel and Hardy feature film Babes in Toyland, Laurel and Hardy are sentenced to the ducking stool, followed by banishment to Boogeyland, for burgling Barnaby's house.[citation needed]

Demise

[edit]The last recorded cases are those of a Mrs Ganble at Plymouth (1808); Jenny Pipes, a "notorious scold" (1809), and Sarah Leeke (1817), both of Leominster. In the last case, the water in the pond was so low that the offender was merely wheeled around the town in the chair.[6] The common law offence of common scold was extant in New Jersey until struck down in 1972 by Circuit Judge McCann who found it had been subsumed in the provisions of the Disorderly Conduct Act of 1898, was bad for vagueness and offended the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution for sex discrimination. Long before this decision, the punishment of ducking, together with all other forms of corporal punishment, had become unlawful under the provisions of the New Jersey Constitution of 1844 or even as early as 1776.[14]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Underdown, David (1985). "The Taming of the Scold: Enforcement of Patriarchal Authority in Early Modern England". In Fletcher, A.; Stephenson, J. (eds.). Order and Disorder in Early Modern England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 116–136. ISBN 0-521-25294-6. OCLC 17289313. Archived from the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2018-05-31.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary includes dishonest tradesmen as well as disorderly women and scolds as people for whom the cucking-stool was used and cites its use in Vienna and that "The punishment of the ducking stool cannot be inflicted in Pennsylvania." which by implication suggests that it could be used in some other parts of the USA. https://oed.com/view/Entry/58195?redirectedFrom=ducking+stool Archived 2023-06-08 at the Wayback Machine accessed 27 Nov 2012.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. "Cucking-stool" has references in 1215-70 and c.1308, including the use of the cucking-stool for immersion in water (c1308, 1534, 1633). https://oed.com/view/Entry/45498?redirectedFrom=cucking-stool#eid Archived 2018-10-27 at the Wayback Machine and ...ducking-stool accessed 27 Nov 2012.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. https://oed.com/view/Entry/58195?redirectedFrom=ducking+stool Archived 2023-06-08 at the Wayback Machine accessed 27 Nov 2012.

- ^ Rollins, Hyder E. (1971). A Pepysian Garland. Harvard University Press. pp. 72–77. ISBN 0-674-66185-0.

- ^ a b c d One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ducking and Cucking Stools". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 631. Citations:

- W. Andrews, Old Time Punishments (Hull, 1890)

- A. M. Earle, Curious Punishments of Bygone Days (Chicago, 1896)

- W. C. Hazlitt, Faiths and Folklore (London, 1905)

- Llewellynn Jewitt in The Reliquary, vols. i. and ii. (1860–1862)

- ^ Cox, James A. "Bilboes, Brands, and Branks Archived 2019-08-10 at the Wayback Machine: Colonial Crimes and Punishments." Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Spring, 2003. Accessed 30 Sept. 2012.

- ^ Behringer, Wolfgang (2004). Witches and witch-hunts: a global history. Themes in history. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 164. ISBN 0-7456-2718-8.

- ^ Shapira, Ian (July 12, 2006). "After Toil and Trouble, 'Witch' Is Cleared". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2022-02-28. Retrieved 2010-10-22.

- ^ Wright, Joe (12 June 2020). "Canterbury's ducking stool at centre of debate after opponents suggest its removal". KentOnline.co.uk. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ "Home - Mittelalterliches Kriminalmuseum". 2021-07-05. Archived from the original on 2023-06-24. Retrieved 2023-06-19.

- ^ "A ghoulish tour of medieval punishments". BBC News. 2 July 2016. Archived from the original on 2017-09-15. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ^ Langland's Piers Plowman, B.V.29.

- ^ State of New Jersey v. Marion Palendrano, 120 N.J. Super. 336 (1972) McCann JCC (Superior Court of New Jersey, Law Division (Criminal) 13 July 1972).