J. Edgar Hoover Building

| J. Edgar Hoover Building | |

|---|---|

The J. Edgar Hoover Building | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Brutalist |

| Address | 935 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Town or city | Washington, D.C. |

| Country | U.S. |

| Coordinates | 38°53′42.7″N 77°1′30.0″W / 38.895194°N 77.025000°W |

| Current tenants | Federal Bureau of Investigation |

| Construction started | March 1965 |

| Completed | September 1975 |

| Inaugurated | September 30, 1975 |

| Landlord | General Services Administration |

| Height | 160 feet (49 m) (E Street NW side) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 11 (E Street NW side) 8 (Pennsylvania Avenue NW side) |

| Floor area | 2,800,876 square feet (260,209.9 m2) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architecture firm | Charles F. Murphy and Associates |

| Other information | |

| Public transit access | |

The J. Edgar Hoover Building is a low-rise office building located at 935 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., in the United States. It is the headquarters of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

Planning for the building began in 1962, and a site was formally selected in January 1963. Design work, focusing on avoiding the blocky, monolithic structure typical of most federal architecture at the time, began in 1963 and was largely complete by 1964, though final approval did not occur until 1967. Land clearance and excavation of the foundation began in March 1965; delays in obtaining congressional funding meant that only the three-story substructure was complete by 1970. Work on the superstructure began in May 1971. These delays meant that the cost of the project grew from $60 million to $126.108 million. Construction finished in September 1975, and President Gerald Ford dedicated the structure on September 30, 1975.

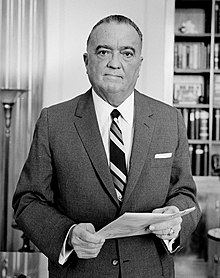

The building is named after former FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. President Richard Nixon directed federal agencies to refer to the structure as the J. Edgar Hoover FBI Building on May 4, 1972, two days after Hoover's death, but the order did not have the force of law. The U.S. Congress enacted legislation formally naming the structure on October 14, 1972, and President Nixon signed it on October 33.

The J. Edgar Hoover Building has 2,800,876 square feet (260,210 m2) of internal space, numerous amenities, and a special, secure system of elevators and corridors to keep public tours separate from the rest of the building. The building has three floors below-ground, and an underground parking garage. The structure is eight stories high on the Pennsylvania Avenue NW side, and 11 stories high on the E Street NW side. Two wings connect the two main buildings, forming an open-air, trapezoidal courtyard. The exterior is buff-colored precast and cast-in-place concrete with repetitive, square, bronze-tinted windows set deep in concrete frames.

Critical reaction to the J. Edgar Hoover Building ranged from strong praise to strong disapproval when it opened.[1] More recently, it has been widely condemned on aesthetic and urban planning grounds.[2]

Plans have been made to relocate the FBI's headquarters elsewhere, but those plans were abandoned in 2017 due to a lack of funding for a new headquarters building.[3][4]

Design and construction

[edit]Planning

[edit]Since 1935, as an element of the United States Department of Justice, the FBI had been headquartered in the Department of Justice Building. In March 1962, the Kennedy administration proposed spending $60 million to construct a headquarters for the FBI on the north side of Pennsylvania Avenue NW opposite the Justice Department. The administration argued that the FBI, which had offices in the Justice Department building as well as 16 other sites in the capital, was too dispersed to function effectively.[5] Initially, prospects for the new building seemed good. A House committee approved the budget request on April 11,[6] and a Senate committee approved it a day later.[7] But the United States House of Representatives deleted the funds when the budget reached the House floor. A budget conference committee then voted in September to restore enough funds for site selection, planning, and preliminary design.[8]

The site selection process for the new FBI headquarters was largely driven by factors unrelated to organizational efficiency. By 1960, Pennsylvania Avenue was marked by deteriorating homes, shops, and office buildings on the north side and the monumental Neoclassical federal office buildings of Federal Triangle on the south side.[9][10] Kennedy noticed the dilapidated condition of the street when his inaugural procession traversed Pennsylvania Avenue in January 1961.[11][12][13] At a cabinet meeting on August 4, 1961,[14] Kennedy established the Ad Hoc Committee on Federal Office Space to recommend new structures to accommodate the growing federal government (which had constructed almost no new office buildings in the city since the Great Depression).[13][15] Assistant Secretary of Labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan was assigned to help staff the committee.[16] In the Ad Hoc Committee's final report, Moynihan proposed (in part) that Pennsylvania Avenue be redeveloped using the powers of the federal government. The report suggested razing every block north of Pennsylvania Avenue from the United States Capitol to 15th Street NW, and building a mixture of cultural buildings (such as museums and theaters), government buildings, hotels, office buildings, restaurants, and retail on these blocks.[10][13][17] Kennedy approved the report on June 1, 1962,[14] and established an informal "President's Council on Pennsylvania Avenue" to draw up a plan to redevelop Pennsylvania Avenue.[11][18]

The site selected by GSA on January 3, 1963, for the new FBI headquarters were two city blocks bounded by Pennsylvania Avenue NW, 9th Street NW, E Street NW, and 10th Street NW. GSA administrator Bernard Boutin said the site was selected after informal consultation with the President's Council on Pennsylvania Avenue and the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC; which had statutory power to approve any major construction in the D.C. metropolitan area). Boutin said construction of the new FBI building would help revitalize the Pennsylvania Avenue area as suggested by both the Ad Hoc Committee on Federal Office Space and the President's Council on Pennsylvania Avenue. Boutin emphasized that the design of the new structure would be in harmony with other buildings planned by the President's Council on Pennsylvania Avenue, and would necessitate the closing of a short section of D Street NW between 9th and 10th Streets NW.[19] More than 100 small retail businesses were to be evicted.[20]

Design

[edit]The early consensus was that the new FBI building would avoid the block-filling style of box-like architecture advocated by the General Services Administration. Staff at the NCPC advocated an aggregation of smaller, interconnected buildings, while President's Council on Pennsylvania Avenue architectural consultant Nathaniel A. Owings suggested that small retail shops be incorporated into the ground floor of the building.[21] Staff at the President's Council on Pennsylvania Avenue said the council would "blow its top" if the FBI headquarters design was monolithic.[22]

In January 1963, GSA estimated that construction on the building would begin in 1964, and be complete in 1967.[19] In June 1963, GSA hired the firm of Charles F. Murphy and Associates to assist with the design.[23][24] Stanislaw Z. Gladych was the chief architect,[25] and Carter H. Manny, Jr. was the partner in charge.[26] Murphy and Associates struggled to meld competing views of what the building should be. The President's Council on Pennsylvania Avenue wanted a building with a pedestrian arcade on Pennsylvania Avenue side, and retail shops on the ground level on the other three sides. But the FBI rejected this view, instead advocating a structure which was bomb-proof on the first few stories and which had but a few, tightly secured access points elsewhere. Murphy and Associates initially designed a monumental building. This approach was rejected by GSA for wasting space and because it would draw criticism for its apparent misuse of taxpayer dollars on lavishness. Murphy and Associates next designed a "Chicago school" structure. This was a rectangular building whose front was aligned along an east–west axis rather than Pennsylvania Avenue. This created a strong setback on Pennsylvania Avenue, which the architects turned into a pedestrian plaza. Although this design was largely accepted, the setback was not and the building's south side was again aligned with the avenue. Although the FBI was not extensively interested in the building's architectural design, mid- and low-level managers meddled extensively in the building's details (even while working drawings were being completed).[26]

With design work still incomplete by April 1964, GSA pushed back the start of construction to 1966.[27] On April 22, GSA announced that, after consulting informally with the NCPC, the FBI building would have two levels. The Pennsylvania Avenue façade would be four to six stories high, while the E Street side would rise to eight or nine stories. The goal was to avoid creating a solid front of monolithic office buildings along Pennsylvania Avenue NW.[28]

On October 1, 1964, the NCPC approved the preliminary design of the FBI building.[23] During the design phase, the architects discovered that the NCPC supported the FBI's desire for a highly secure building, and this influenced the structure's design significantly.[26][29] The plans by Murphy and Associates called for an eight-story structure on Pennsylvania Avenue and a 12-story building along E Street. The two buildings were connected by wings along 9th and 10th Streets NW, forming an open-air courtyard in the interior. A portion of these wings would push underground into the hill which rose behind Pennsylvania Avenue. The building was set back 70 feet (21 m) from Pennsylvania Avenue. It also had underground parking accessible from 9th and 10th streets.[23] An open deck, designed to allow pedestrians to enter on E Street and stroll along the second floor of the building, existed on the east and west sides of the FBI building.[26] The architects noted that this deck could be extended on the south (Pennsylvania Avenue) side.[23] The NCPC voiced only one concern. It worried that the "penthouses" atop the building (which were designed to conceal the HVAC and elevator equipment) were illegal. The penthouses raised the building's height to 172 feet (52 m)—12 feet (3.7 m) higher than permitted by law.[23]

The United States Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) reviewed the plans on October 21, 1964.[25][30] GSA and Murphy and Associates had declined to make the FBI building's plans public prior to this meeting.[23] During informal discussions with CFA staff in the initial design phase, the architects learned that the CFA wanted the FBI building to have a powerful base which appeared to anchor it to the earth.[26] Although this was in direct conflict with the open architecture advocated by the President's Council on Pennsylvania Avenue, it was more in line with what the NCPC and FBI wanted. Since it was not clear whether the proposed design that had met with NCPC approval would be accepted by the CFA, the design was confidential so that changes could still be made without the appearance that they had been forced on the architects. The still-incomplete designs unveiled during the CFA meeting now showed a massive, three-story roof deck overhanging the main building on E Street, with glass curtain wall-enclosed walkways connecting the Pennsylvania Avenue building to the 9th and 10th street wings. The trapezoidal interior courtyard was designed to hold sculpture and accommodate public exhibits about the FBI. The façade now exhibited repetitive, angular concrete elements similar to those used by Le Corbusier in the Punjab and Haryana High Court in Chandigarh, India; Paul Rudolph in his Brutalist Yale Art and Architecture Building at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut; and Gyo Obata in the final design for the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.[25]

Funding and construction

[edit]Although the Commission of Fine Arts did not approve the FBI building's final design until November 1967,[31] the first contract for land clearance and excavation was awarded in March 1965.[24] GSA also moved ahead with funding requests for construction in 1965. But securing that funding proved elusive. A Johnson administration request for $45.8 million in initial funding was denied by the House Appropriations Committee in May.[32] Although both administration and FBI officials expressed confidence that the money would be restored,[33] a House–Senate budget conference committee in August declined to include the funds in the fiscal 1966 budget.[34]

The funding request fared better in 1966. Once again, the House Appropriations Committee cut the administration's $45.7 million funding request in May.[35] But with the land for the structure almost completely cleared, GSA would be left holding an empty lot if funding was not forthcoming. This prompted Congress to act. In October, a House–Senate budget conference committee recommended spending $11.3 million to excavate and build the foundation and to pour the first floor's concrete slab. Both chambers of Congress approved this expenditure late in the month.[36]

Design issues continued to plague the project, however. Throughout 1966, private developers fought with the General Services Administration in hearings before the NCPC, which was closing in on a decision to give final approval to the project. At issue were the 20-foot (6.1 m) high equipment penthouses atop the building. Private developers demanded that they be given the right to raise their buildings by the additional height as well, while other government agencies argued that giving the FBI building a height waiver would set a bad precedent and weaken government height restrictions along Pennsylvania Avenue. With the overhanging roof deck of the FBI building already having lost one of its three stories,[37] the NCPC agreed to the waiver on December 1, 1966.[38] Meanwhile, the President's Council on Pennsylvania Avenue was still pushing for an arcade on the ground level along Pennsylvania Avenue NW. The Council argued that all buildings along Pennsylvania Avenue should include an arcade so that pedestrians could walk along the street somewhat protected from the elements. The FBI and private developers both opposed the arcade requirement. The Council believed that if the FBI were given an exemption from the requirement, it would be unable to enforce it with other builders. The FBI won the day by arguing that rapists and muggers would hide in the arcades, making Pennsylvania Avenue unsafe for pedestrians and workers. The NCPC agreed, and voted in favor of an exemption on September 14, 1967.[39]

Congress appropriated a total of $20.5 million in fiscal 1968, 1969, and 1970 to complete work on the substructure. The first contract for construction of the three-story substructure was awarded in November 1967.[40] By October 1969, construction of the substructure was under way.[41] By June 1970, however, the cost for the FBI building had ballooned to $102.5 million. GSA officials blamed inflation for the cost increase. At the same time, GSA said that the contract for construction of the third story of the substructure was due to be awarded in March 1971.[40] That contract went to Blake Construction.[42] Construction of the eight-story Pennsylvania Avenue building, 11-story E Street building, and wings was estimated in June 1970 to begin in late 1973 or early 1974.[40]

Bids for work on the $68 million superstructure were opened in May 1971, and the job again awarded to Blake Construction.[42] In December 1971, GSA announced that the cost of the building had risen by $7 million in the past year (to $109 million) due to inflation, a major design change, and the cost of the building's unusual features. The design change added 15,800 square feet (1,470 m2) of office space,[24] but also included special blast-proof paving around the building.[29] Just a month later, in January 1972, GSA reported that the cost of the building had risen to $126.108 million. A new completion date of July 1974 was also announced.[29] GSA later capped the building's cost at $126.108 million in August 1972. The agency blamed the cost increase on inflation; the use of different contracts for excavation, substructure construction, and superstructure construction; the construction of a pneumatic tube system, reinforced flooring, and a special fire detection and suppression system; and the unique requirements of the areas for the fingerprinting bureau. The agency also said that NCPC and CFA alterations increased the cost by $7.465 million.[43]

By August 1972, the substructure was complete; the floor, columns, and roof of the first floor installed; and second floor columns poured. Although Congress had authorized $126.108 million for the FBI building, it had yet to appropriate the money.[43]

The FBI building neared completion in 1974. The first FBI personnel began moving into the building in October 1974, and FBI Director Clarence M. Kelley moved into his office in May 1975. By June 1975, the structure was 45 percent occupied. Construction on the building was due to end in September 1975, with the final personnel arriving in November 1975.[44]

President Gerald Ford dedicated the J. Edgar Hoover Building on September 30, 1975.[45]

Naming

[edit]

Although the FBI building originally had no name, there were expectations that it would, in time, be dedicated to J. Edgar Hoover. Washington Post reporter Walter Pincus speculated in June 1971 that Hoover's name would be eventually attached to the building.[42] Reporter Abbott Combs made the same claim in December 1971.[24]

J. Edgar Hoover died on May 2, 1972. On May 3, the day after Hoover's death, the United States Senate passed a resolution asking that the incomplete FBI building be named for Hoover.[46] The following day, President Richard Nixon directed the General Services Administration to designate the structure as the J. Edgar Hoover Building.[47][48] Neither the Senate resolution nor Nixon's order had the force of law, however.

On May 25, 1972, as part of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial Bicentennial Civic Center Act, the Senate passed legislation (S. 3943) legally designating the FBI building as the J. Edgar Hoover Building.[49][50] A similar bill in the United States House of Representatives (H.R. 16645) was also moving forward. The House bill was amended several times.[50] The House subsequently passed S. 3943 on October 3, after amending it to include the amended language of H.R. 16645.[51] The Senate agreed to the House amendments on October 14.[50] Nixon signed the legislation into law as Public Law 92–520 on October 21, 1972.[52][53]

Architecture

[edit]At the time it was completed, the J. Edgar Hoover building was reported to have 2.4 million square feet (220,000 m2)[42] to 2.535 million square feet (235,500 m2)[29] of interior space, of which 1 million square feet (93,000 m2) were usable office space.[42] According to more current information provided by the FBI, the building contained 2,800,876 square feet (260,209.9 m2) of interior space in 2010.[54] Its internal amenities included:[24][29][42][55]

- An amphitheater

- A 162-seat auditorium

- An automobile repair shop

- A two-story basketball court

- An eighth-floor cafeteria, with access to a roof garden

- Classrooms

- Cryptographic vault

- Developing laboratories for both still photography and motion pictures

- Exercise rooms

- A film library

- A firing range

- 80,000 square feet (7,400 m2) of laboratory space

- A medical clinic

- Morgue

- A printing plant

- A test pattern and ballistics range

- A 700-seat theater

The structure has three floors below ground. Originally only two below-ground floors were planned, but a third was added during the review process.[29] The top two floors of the northern (E Street) structure housed the fingerprint bureau.[42] Special features of the building included a pneumatic tube system and a conveyor belt system for handling mail and files.[24] A special, reinforced, extra-thick "protection slab" existed beneath the second floor to help protect the building from street-level explosions.[29] A gravel-filled dry moat ran along the building on E Street NW.[56]

The building's corner piers contained the mechanical services (elevators, HVAC, etc.). A dual elevator system was installed, one for use by the public and one for use by staff. A dual set of hallways also existed in portions of the buildings. The smaller set of dual hallways was for public use. The public elevators connected only to the public hallways, isolating the public from FBI workers.[29] Several portions of the public hallway contained glass partitions through which the public could see FBI personnel at work.[55]

The J. Edgar Hoover Building is in an architectural style known as Brutalism.[57][58] The term is derived from the French term béton brut ("raw concrete"); in Brutalist structures, unprocessed concrete surfaces are commonly used to create "rugged, dramatic surfaces and monumental sculptural forms."[59] The concrete of the Hoover Building shows the marks from the rough wood forms into which the liquid concrete was poured. The exterior is constructed of buff-colored precast and cast-in-place concrete.[29][60] The intent was to attach sheets of polished concrete or granite to the exterior. The exterior walls were built to accommodate these attachments, but this plan was abandoned as the building neared completion.[55] The windows were of bronze-tinted glass.[45] The cornice line is 160 feet (49 m) high on the E Street side.[61] The interior, as built, consisted of white vinyl floor tiles, and polished concrete ceilings and floors painted white.[60] The open-air courtyard was paved with grayish-beige stone, and contained an arcade to shelter employees as they moved around its edge.[60]

Critical reception

[edit]

The J. Edgar Hoover Building was widely praised when first erected. Washington Post architectural critic Wolf Von Eckardt called it "gutsy" and "bold" architecture in 1964. It was, he asserted, "...masculine, no-nonsense architecture appropriate for a national police headquarters. It is a promising beginning for the new Pennsylvania Avenue."[25] Chicago Tribune critic Paul Gapp was more equivocal. Writing in 1978, he felt the uneven cornice line gave "the taller facades of the building a rather intimidating, temple-like look vaguely reminiscent of an old Cecil B. Dé Mille set". He also criticized the open second deck for having a dark, cavernous look and the interior for being "Federal drab". But on balance, Gapp wrote, while the FBI building "falls considerably below C.F. Murphy's general level of design excellence[,] ...it is not the visual disaster some of its detractors have made it out to be." He declared it mediocre architecture, but not worse than any other federal building built in Washington, D.C., the past decade.[26] New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable was also less enthusiastic. Although she enumerated several of the building's flaws, she nonetheless felt the design did a "superior job" in reconciling numerous problems facing the site and the uses to which the structure would be put.[29]

Von Eckardt's views on the FBI building changed radically between his initial assessment in 1964 and the structure's completion in 1975.[1] At its dedication, he called the building Orwellian, "alien to the spirit of the capital", and an "overly dramatic and utterly miscarried play of forms". He criticized the interior as "a drab factory with harsh light, endless corridors, hard floors and no visual relief". Von Eckardt did not blame the architects for the building's design, but rather the CFA.[56] Paul Goldberger, writing for the New York Times, echoed Von Eckardt's harsh assessment. He felt the design banal and dull, "an arrogant, overbearing concrete form that dares the visitor to come close." He noted that the high, strong massing on E Street was reminiscent of a similar rear massing on Le Courbousier's Priory at Sainte Marie de La Tourette, but lacked the dramatic hill behind it to give the massing a counterpoint. "This building," he concluded, "turns its back on the city and substitutes for responsible architecture a pompous, empty monumentality that is, in the end, not so much a symbol as a symptom—a symptom of something wrong in government and just as wrong in architecture."[60]

More recently, the J. Edgar Hoover Building has been strongly criticized for its aesthetics and impact on the urban life in the city. In 2005, D.C. architect Arthur Cotton Moore harshly condemned the building for creating a dead space in the heart of the nation's capital. "It creates a void along Pennsylvania Avenue. Given its elephantine size and harshness, it creates a black hole. Its concrete wall, with no windows or life to it, is an urban sin. People should be strolling down America's main street. Nobody strolls in front of the FBI Building."[62] The following year, Gerard Moeller and Christopher Weeks wrote in the AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D.C. that the FBI building was the "swaggering bully of the neighborhood...ungainly, ill-mannered..." They also blamed the structure's poor design for undermining the redevelopment of Pennsylvania Avenue: "the impenetrable base, the shadowy courtyard, and looming upper stories bespeak security and surveillance. The prototype for the Pennsylvania Avenue redevelopment plan devised under the direction of Nathanial Owings, it helped to ensure that the full plan would never be realized."[63] Five years later, in 2011, Washington City Paper reporter Lydia DePillis noted that the building has "long been maligned as downtown D.C.'s ugliest edifice".[64] Architecture for Dummies author Deborah K. Dietsch said in April 2012 that it was "disastrous", "insensitive", and "hostile", and that it and the James V. Forrestal Building topped the list of the city's ugliest buildings.[65] A list compiled by Trippy.com and Reuters declared the J. Edgar Hoover Building the world's ugliest building, and found it to be a "dreary 1970s behemoth".[66] Los Angeles Times travel writer Christopher Reynolds remarked that the Hoover building is "so ugly, local historians say, that it scared authorities into setting higher standards for pedestrian friendliness among buildings along [Pennsylvania Avenue]".[67]

Perhaps the most critical—and most important—criticism has come from the National Capital Planning Commission and the Commission of Fine Arts themselves. In 2009, the two agencies released a major new strategic study and plan for the future of the city of Washington, D.C., the Monumental Core Framework Plan. Although the two agencies stopped short of asking the federal government to tear the J. Edgar Hoover Building down, the two agencies were trenchant in their criticism:

- ...the FBI's security requirements have prevented street-level public uses around the entire block of the J. Edgar Hoover Building between 9th and 10th Streets. The building's fortress-like presence is exacerbated by security installations, the moat that surrounds three sides of the building, the scale of its architectural features, and the absence of street-level activity. ...[R]edevelopment of the J. Edgar Hoover Building site with cultural, hospitality, commercial, and office uses can bring new urban vitality to Pennsylvania Avenue.[68]

Artwork

[edit]The courtyard of the building includes the sculpture Fidelity, Bravery, Integrity by Frederick Charles Shrady. In January 1975, the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI passed a resolution to create a memorial to J. Edgar Hoover. The memorial, which cost $125,000, was funded through contributions. The artist was selected through a design contest, and the sculpture dedicated on October 13, 1979. The piece, made of bronze (15 feet 7 inches (4.75 m) wide and 5 feet 7 inches (1.70 m) deep), shows three figures which represent Fidelity, Bravery, and Integrity. The figures are placed against a backdrop of a large United States flag, which appears to wave in the breeze. Fidelity, a female, is on the right, seated on the ground and looking up at a male figure of Bravery. To the left of Bravery is Integrity, a male figure who kneels on one knee, with his left hand on his heart. He looks towards Bravery, who stands flanked by the two other figures. The figures are simple with little detail. The sculpture rests on a rectangular base 2 feet 6 inches (0.76 m) by 10 feet 3 inches (3.12 m) by 7 feet 4 inches (2.24 m) made of slabs of black marble and mortar. The front of the base is carved and painted with the words "Fidelity, Bravery, and Integrity". In 1993, the piece was surveyed as part of the Smithsonian Institution's Save Outdoor Sculpture! and was described as needing conservation treatment.[69]

Decay and potential replacement

[edit]The FBI immediately closed the second-story pedestrian observation deck for security reasons when the building opened in 1975.[26] It has not been reopened to the public since. The agency suspended public tours of the J. Edgar Hoover Building in the wake of the September 11 attacks.[70] The tours remained suspended as of April 3, 2019.[71]

Structural problems with the J. Edgar Hoover Building became apparent around 2001. That year, an engineering consultant found that the building was deteriorating due to deferred maintenance and because many building systems (HVAC, elevators, etc.) were nearing the end of their life-cycle. The consultant rated the building as in "poor condition" and said it was not at an "industry-acceptable level".[72]

Additional studies of the building were made over the next several years. In 2005, a real estate consultant reported that the FBI's scattered workforce (then housed in the Hoover building and 16 other leased sites throughout the D.C. metropolitan area) and the Hoover building's inefficient interior layout were creating workforce inefficiencies for the FBI. Security upgrades, building systems replacements, and other renovations were suggested. At this time, GSA estimated that it would take three years to develop a replacement headquarters and identify a site, and another three years for design, construction, and move-in.[73] The FBI began studying the costs and logistics of moving its headquarters later that year.[74]

In 2006, GSA estimated the costs of renovating the Hoover Building at between $850 million to $1.1 billion.[75] Additional problems also became apparent that same year. A piece of the concrete façade came loose and fell onto the sidewalk on busy Pennsylvania Avenue NW. A contractor was hired to remove loose concrete from the exterior. Construction netting was hung around the upper floors to prevent additional pieces of concrete from crashing to the ground. The total cost of the concrete removal and safety netting installation was $5.9 million.[76] In 2007, an architectural design and planning consultant reported that the cost of these renovations and the disruption to FBI work and staff were not justifiable. The consultant recommended building a new FBI headquarters.[77]

In 2008, a real estate appraisal firm was hired by GSA to further evaluate the J. Edgar Hoover building. The firm rated the construction of the building as average and the condition of the building below average. The consultant also said the Hoover building was inferior in both design and construction in comparison to other office buildings built at the same time. The appraiser also said that even if GSA made all $660 million in identified urgent renovations, the J. Edgar Hoover Building would still not be classified as "Class A" office space.[78]

The onset of the Great Recession forced the FBI to suspend its efforts to build a new headquarters.[74] In 2010, GSA downgraded the Hoover building from a "core asset" (a structure whose useful life is longer than 15 years) to "transition asset" (a structure whose useful life is six to 15 years). In making the downgrade, GSA decided to limit renovations to the building.[79]

In 2011, a Government Accountability Office (GAO) inspection of the Hoover Building revealed additional major deterioration. Water seeping from the interior courtyard had corroded the concrete ceiling of the parking garage below.[80] McMullan & Associates, a structural contractor, reported that the parking garage was "severely deteriorated", and that loose pieces of concrete were in "imminent danger of releasing" from the garage roof. McMullan & Associates called the issue life-threatening, and removed loose concrete to mitigate the problem.[76] GSA also reported that the building basement was prone to flooding when it rained.[80] GAO concluded that the building was "aging" and "deteriorating",[81] that the Hoover Building's original design was inefficient, and that the building could not be easily reconfigured to create new workspace or encourage intra-agency cooperation.[82]

The GAO report also identified major security risks to FBI personnel in the D.C. metropolitan area because of the Hoover building's limitations. The Hoover building is surrounded on all sides by busy city streets which are just a few feet from the structure. Additionally, because the Hoover Building is too small to accommodate the FBI's post-9/11 activities, the agency has leased space in 21 locations throughout the metro area,[83] nine of which are in multi-tenant buildings.[84] The FBI admitted its internal security forces are not stationed at these leased spaces, but merely patrol them periodically.[81]

The Government Accountability Office in November 2011 recommended four options for the J. Edgar Hoover Building:[81]

- Do nothing.

- Renovate the Hoover Building over 14 years at a cost of $1.7 billion.

- Demolish the Hoover Building and rebuild at the same site. This would take nine years and cost $850 million.

- Build a new headquarters elsewhere. This would take seven years and cost $1.2 billion.

The FBI, in agreeing with the GAO's report, said its highest priority was to abandon the J. Edgar Hoover Building and to construct a new, larger headquarters capable of bringing the FBI's scattered workforce under one roof, improving intra-agency efficiency, and reducing building operational and maintenance costs.[85]

Following on the heels of the GAO report, in December 2011 the United States Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works voted unanimously to authorize and direct the GSA to identify a firm to build a secure rental facility containing up to 2.1 million square feet (200,000 m2) on a federally owned site of up to 55 acres (22 hectares) within 2 miles (3.2 km) of a Washington Metro rail station to accommodate all FBI headquarters staff in the National Capital Region. Under this scheme, the federal government would provide guarantees to help finance the structure, which would then be leased to the federal government for two decades—after which time the government would take ownership of the building.[74][86] Three suburban counties, Fairfax and Loudoun in Virginia and Prince George's in Maryland, all expressed interest in hosting the new headquarters.[87] In April 2012, the Washington Business Journal speculated that the a new FBI building might be built in a neighborhood of Washington, D.C., in need of revitalization and urban renewal (such as Ward 7 or Ward 8). At that time, GSA's commissioner of the Public Building Service, Bob Peck, said that GSA preferred to sell the Hoover building and its site to a private developer and not specify whether the structure should be maintained or demolished.[65] But the Senate resolution was not adopted by the House of Representatives, and did not become law in the 112th United States Congress. However, on November 29, 2012, the Fairfax Times reported that Fairfax County officials believed Congress would consider this legislation anew in 2013, and the county moved to hire lobbyists to encourage construction of the new FBI headquarters on a government-owned location near the Franconia-Springfield Metro station.[88]

Search for a new headquarters

[edit]Building swap proposal of 2013

[edit]On December 3, 2012, the General Services Administration announced that it would entertain proposals from private-sector developers to swap the J. Edgar Hoover Building for a larger parcel of land outside the city. GSA asked interested developers to offer undeveloped property as well as cash for the Hoover building. GSA Acting Administrator Dan Tangherlini said the agency hoped the cash infusion would enable the FBI to build its new headquarters. A deadline of March 4 was established for proposals.[89] A few weeks later, Montgomery County, Maryland officials said they were soliciting private developers to help them form a bid for the new FBI headquarters as well.[90]

The GSA held an "industry day" on January 17, 2013, to judge interest in the proposal and informally solicit ideas from developers. According to GSA officials, the overflow crowd of 350 people made the event "the largest for any such offering in memory".[91][92] Patrick G. Findlay, FBI assistant director for facilities and logistics services, said that any new FBI headquarters must be at least 2.1 million square feet (200,000 m2) in size, accommodate 11,000 employees, and contain 40 to 55 acres (16 to 22 ha) of land.[92] GSA Acting Administrator Dan Tangherlini affirmed that the GSA still believed it would be too costly to renovate the J. Edgar Hoover Building, or to demolish it and rebuild on the same site. Tangherlini also said the GSA would take into consideration the 2011 Senate resolution's requirements that any new FBI headquarters be located within 2 miles (3.2 km) of a Metrorail station and no more than 2.5 miles (4.0 km) from the Capital Beltway. GSA announced a new deadline of March 24, 2013, for "expressions of interest" and said it was likely to issue a formal request for proposals by the end of 2013.[91]

Before the GSA "industry event" D.C. officials also expressed interest in keeping the FBI headquarters within the city limits.[91] D.C. Mayor Vincent C. Gray said the city would also submit its proposals, and Gray suggested using Poplar Point—a 110-acre (45 ha) parcel of federally owned land bordered by the Anacostia River, South Capitol Street, Interstate 295 (also known as the Anacostia Freeway), and the 11th Street Bridges.[92][93] Gray said on February 26 that, although it had conducted FBI relocation studies before, a new cost-benefit analysis of moving the FBI headquarters to Poplar Point would be complete in 60 days. The Washington Post reported that Gray and D.C. City Council member Tommy Wells appeared to doubt the value of keeping the FBI in the District. "While politics might demand that the District not bow out of the regional derby entirely," reporter Mike DeBonis said, "a sensible look at the city's future growth might also demand concluding that a high-security government compound is not a wise use of a prime development parcel."[94]

The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) also joined the bidding for the new FBI headquarters. WMATA has 78 acres (32 ha) of land near its Greenbelt Metrorail station in Prince George's County. WMATA previously signed an agreement with real estate development company Renard (formerly Metroland Developers) under which the company would develop the empty land (generating property lease income for WMATA). Metro officials proposed amending the agreement to permit Renard and Prince George's County officials to submit the land for consideration by GSA. If the proposal is accepted, Renard would be required to buy the land at market value. Alternatively, Renard could transfer its development rights to Prince George's County, which could then submit a bid. WMATA officials noted that the site is served by Metrorail, and there are 3,700 parking spaces and 17 Metrobus bays at the Greenbelt station. WMATA believed that the federal government would pay to improve Capital Beltway access to (which is currently very limited) and upgrade WMATA facilities at the station (at no cost to the transit agency).[95]

Real estate developer Donald Trump expressed his interest in redeveloping the Hoover building in September 2013. Trump obtained a 60 years lease for the Old Post Office Pavilion across the street in the summer of 2013, and plans to invest $200 million and plans to remodel it in order to convert it into a luxury hotel. Trump estimated that the FBI would not vacate the Hoover Building until 2016.[96]

Formal site selection process

[edit]On November 14, 2013, GSA opened a formal process for selecting the site of a new FBI headquarters. The agency said it received 38 informal proposals from area governments and developers, which demonstrated enough interest from viable projects that it should move ahead with a formal relocation. The agency set a deadline of December 17, 2013, for formal proposals, and said it would choose one or more of locations for additional discussion in early 2014. A single location and development partner was likely to be chosen by mid-2014, and a formal agreement signed in 2015.[97]

GSA said its requirements for a new headquarters site included:[97]

- 50 acres (200,000 m2) of land, or 2.1 million square feet (200,000 m2) of office and parking space.

- Within 2 miles (3.2 km) of a Washington Metro station

- Within 2.5 miles (4.0 km) of the Capital Beltway

- The site must be within the District of Columbia; Montgomery or Prince George's counties in Maryland; Arlington, Fairfax, Loudoun, or Prince William counties in Virginia; or the independent cities of Alexandria, Fairfax, Falls Church, Herndon, Manassas or Vienna in Virginia.

- Level V security, the highest standard required by the federal government.

- Access to public utilities.

Because of their distance from Metrorail and the Beltway, Loudoun and Prince William counties were effectively eliminated from the competition.[97] Victor Hoskins, D.C.'s deputy mayor for planning and economic development, acknowledged that the city's proposed site, Poplar Point, was also eliminated due to the small size and environmental concerns.[98] Several prominent Virginia politicians, including Senators Mark Warner and Tim Kaine, U.S. Representatives Gerry Connolly, Jim Moran, and Frank Wolf, and Governor Terry McAuliffe have come together to lobby for the new site to be built in Springfield after "site-selection guidelines all but eliminated other Northern Virginia locations". The entire Maryland congressional delegation has united to lobby for Prince George's County as the new location.[99]

Environmental impact statement

[edit]In July 2014, GSA announced that the FBI headquarters would relocate from downtown Washington to a suburban campus at a site in Greenbelt or Landover in Maryland or in Springfield, Virginia.[100] In early September 2014, GSA issued a notice of intent to prepare an environmental impact statement (EIS) for the proposed FBI headquarters consolidation and the exchange of the J. Edgar Hoover Building. The notice described the three site alternatives and announced a scoping process that GSA will conduct from September 8 through October 23, 2014. The scoping process is intended to aid in determining the alternatives to be considered and the scope of issues to be addressed, as well as to identify the significant environmental issues that GSA should address during the preparation of a draft EIS. The process includes four open-house type public meetings that GSA will conduct in Maryland, Virginia, and Washington, D.C., during late September and early October 2014 and opportunities for the submission of written comments.[101][102][103]

Recent developments

[edit]In January 2016, the GSA issued Phase II of its Request for Proposals for the project.[104]

The University System of Maryland has bolstered the Maryland sites' bids with its National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism proposing a new Maryland Academy for Innovation and National Security that would be a partnership between the FBI and the University of Maryland, Baltimore and the University of Maryland, College Park.[104]

In October 2016, it was announced that the final site selection for the project, among the three finalist sites of Greenbelt, Maryland; Landover, Maryland; and Springfield, Virginia, would be announced by the end of 2016, although this was subsequently delayed to spring 2017.[104] In July 2017, the GSA announced that it would not proceed with the project, citing lack of adequate funding for the property swap and construction.[4][3]

In October 2018 some members of Congress sent a letter to Emily Murphy, administrator of GSA, attributing the decision to abandon plans to relocate the FBI building to Donald Trump.[105]

In November 2023, the GSA announced that it had selected a site in Greenbelt, Maryland for construction of the new headquarters. However, the following day in an internal message to employees, FBI Director Christopher Wray voiced concerns on the decision due to conflicts of interest in the selection process.[106][107][108]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Von Eckardt, Wolf (August 10, 1975). "America's monument to the FBI". Lewiston Morning Tribune. (Idaho). (Washington Post). p. 5A.

- ^ "Everyone Hates the FBI's J. Edgar Hoover Building. Here's Why Everyone's Completely Wrong". Bloomberg.com. July 30, 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ a b The Associated Press (July 11, 2017). "The FBI Headquarters Is No Longer Moving States". Fortune. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ a b O'Connell, Jonathan; McCartney, Robert; Portnoy, Jenna (July 11, 2017). "Fallout from FBI headquarters decision leaves losers all around". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on December 31, 2017. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ^ Jackson, Luther P. "Two New U.S. Buildings, Renovation of 26 Asked." Washington Post. March 30, 1962.

- ^ "Two U.S. Buildings Here Part of $161 Million Plan." Washington Post. April 11, 1962.

- ^ "Senate Unit Backs New FBI Home." Washington Post. April 12, 1962.

- ^ "Cash for New FBI Home Restored to GSA Budget." Washington Post. September 21, 1962.

- ^ Bednar, p. 24.

- ^ a b Glazer, p. 151.

- ^ a b Schrag, p. 68.

- ^ White, Jean M. "Avenue Grand Design Admired by Goldberg." Washington Post. September 29, 1964; White, Jean M. "Pennsylvania Ave. Designs Must Win Johnson's Support." Washington Post. December 12, 1963.

- ^ a b c Peck, p. 82.

- ^ a b Kennedy, John F. "Memorandum Concerning Improvements in federal Office Space and the Redevelopment of Pennsylvania Avenue." June 1, 1962. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Accessed September 30, 2012.

- ^ Gutheim and Lee, p. 323.

- ^ Schellenberg, p. 132.

- ^ Hess, p. 114-115; Hodgson, p. 79-81; Schellenberg, p. 133.

- ^ Hess, p. 115; Hodgson, p. 80; Von Eckardt, Wolf. "It Could Be a Grand, Glorious Avenue." Washington Post. May 31, 1964.

- ^ a b White, Jean M. "Block to North of Pennsylvania Ave. Selected as Site for New FBI Building." Washington Post. January 3, 1963.

- ^ Bradley, Wendell P. "New FBI Site Will Oust 100 Merchants." Washington Post. January 4, 1963.

- ^ Bradley, Wendell P. "FBI Building May Be Giving Ave. New Life." Washington Post. January 5, 1963.

- ^ Clopton, Willard. "Council Held Confident On FBI Building Plan." Washington Post. January 27, 1963.

- ^ a b c d e f Aarons, Leroy F. "Group Hails Design for FBI Offices." Washington Post. October 2, 1964.

- ^ a b c d e f Combs, Abbott. "FBI Building Costs Set at $109 Million." Washington Post. December 11, 1971.

- ^ a b c d Von Eckardt, Wolf. "New 'Federal' Style Is Emerging For Government Office Buildings." Washington Post. October 22, 1964.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gapp, Paul. "FBI Building—Mediocrity Frames a Macho Image." Chicago Tribune. January 8, 1978.

- ^ "FBI Building Bids Seen in '66." Washington Post. April 21, 1964.

- ^ "Two Heights Planned for FBI's Home." Washington Post. April 23, 1964.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Huxtable, Ada Louise. "The F.B.I. Building: A Study in Soaring Costs and Capital Views On Beauty." New York Times. January 24, 1972.

- ^ Although the CFA is an advisory body, builders rarely proceeded without its approval. Under the Shipstead-Luce Act of 1930, however, CFA approval is required for the erection or alteration of any building on Pennsylvania Avenue NW between the US Capitol and White House and any street abutting it. See: Gutheim and Lee, p. 208.

- ^ The CFA never completely resolved its many concerns with the building. See: Kohler, p. 95-97.

- ^ Eagle, George. "FBI Is Refused $45.8 Million For New Offices." Washington Post. May 7, 1965.

- ^ Clopton, William. "Officials Confident of FBI Office Funds." Washington Post. May 8, 1965.

- ^ "Hill Conferees Drop Funds for New FBI Home, Patent Office." Washington Post. August 5, 1965.

- ^ "Funds for New FBI, Labor Buildings Killed by House Appropriations Unit." Washington Post. May 6, 1966.

- ^ Carper, Elsie. "Funds Assured For FBI Building." Washington Post. October 22, 1966.

- ^ Kohler, p. 97.

- ^ "FBI Building Approved After Penthouse Fight." Washington Post. December 2, 1966.

- ^ Severo, Richard. "Plans Approved for FBI Building." Washington Post. September 15, 1967; Von Eckardt, Wolf. "Avenue Will Have A Missing Tooth." Washington Post. October 22, 1967.

- ^ a b c Hailey, Jean R. "New Home for FBI Expected To Be Costliest U.S. Building." Washington Post. June 19, 1970.

- ^ "A New Start for Pennsylvania Avenue." Washington Post. October 11, 1969.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pincus, Walter. "Hoover's Lasting Monument: New Headquarters for FBI." Washington Post. June 9, 1971.

- ^ a b Donin, Robert. "Halt Claimed to FBI Building Cost Rise." Washington Post. August 12, 1972.

- ^ Robinson, Gail. "FBI Moves After 8 Years, $126 Million." Washington Post. June 21, 1975.

- ^ a b Goshko, John. "Ford Dedicates $126 Million FBI Building." Washington Post. October 1, 1975.

- ^ Graham, Fred. "J. Edgar Hoover, 77, Dies." New York Times. May 3, 1972.

- ^ Nixon, Richard. "Eulogy Delivered at Funeral Services for J. Edgar Hoover." May 4, 1972. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Accessed September 29, 2012.

- ^ "New FBI Building Named for Hoover." Washington Post. August 3, 1972.

- ^ "Washington: For the Record, May 25, 1972." New York Times. May 26, 1972.

- ^ a b c Legislative Reference Service, p. 172.

- ^ Scientific and Technical Information Office, p. 338.

- ^ Scientific and Technical Information Office, p. 358.

- ^ United States Statutes At Large, p. 1021.

- ^ "History of FBI Headquarters". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved October 30, 2010.

- ^ a b c Newton Jones, Linda. "Workers React to New Offices." Washington Post. October 1, 1975.

- ^ a b Von Eckardt, Wolf. "New FBI Building: Perfect Stage Set For Orwell's '1984'." Washington Post. July 12, 1975.

- ^ Tim Weiner (November 1, 2016). "The Long Shadow of J. Edgar Hoover". New York Times.

- ^ Weeks, p. 99.

- ^ Flowers, Benjamin (2011). "Brutalism". The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art. Vol. 1. Oxford University. pp. 356–357. ISBN 9780195335798.

- ^ a b c d Goldberger, Paul. "$126-Million F.B.I. Building, Named For Hoover, Dedicated in Washington." New York Times. October 1, 1975.

- ^ Washington Post reporter Gail Robinson cited the height of the building on E Street as 1,260 feet (380 m). See: Robinson, Gail. "FBI Moves After 8 Years, $126 Million." Washington Post. June 21, 1975. This is clearly inaccurate. A standard reference work on the FBI, as well as real estate datamining company Emporis both list the height at a more believable 160 feet (49 m). Emporis says its data is based on fire insurance maps. See: Theoharis, p. 253; "J. Edgar Hoover Building." Emporis.com. 2012.[usurped] Accessed October 12, 2012.

- ^ Adelman, Ken. "What I've Learned: Arthur Cotten Moore." Washingtonian. October 1, 2005. Accessed October 1, 2012.

- ^ Moeller and Weeks, p. 128.

- ^ DePillis, Lydia. "The FBI Building is a Disaster." Washington City Paper. November 9, 2011. Accessed October 1, 2012.

- ^ a b Dietsch, Deborah K. "Replacing D.C. Eyesores." Washington Business Journal. April 6, 2012. Accessed September 29, 2012.

- ^ Quoted in Austermuhle, Martin. "D.C.'s World-Class Eyesore." Washington Post. May 7, 2012. Accessed October 1, 2012.

- ^ Reynolds, Christopher. "America's Main Street America." Los Angeles Times. April 26, 1992.

- ^ National Capital Planning Commission and Commission of Fine Arts. Monumental Core Framework Plan. Washington, D.C.: NCPC and CFA, 2009, p. 68, 70. Accessed October 1, 2012.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution (1993). "Fidelity, Bravery, Integrity, (sculpture)". Save Outdoor Sculpture, District of Columbia survey. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved December 26, 2010.

- ^ "Update: Tourist Activities and Attractions in Washington, D.C." Washington Post. September 23, 2001.

- ^ "FBI Education Center." FBI.gov. No date. Accessed November 29, 2016.

- ^ "Government Accountability Office, p. 42" (PDF).

- ^ "Government Accountability Office, p. 42-43" (PDF).

- ^ a b c Clark, Charles A. "Plan to Relocate FBI Headquarters Advances." GovExec.com. December 9, 2011. Accessed September 29, 2012.

- ^ "Government Accountability Office, p. 44" (PDF).

- ^ a b "J. Edgar Hoover Building Exterior Emergency Survey, Washington, D.C." McMullan & Associates. www.MCMSE.com. 2012. Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Accessed September 29, 2012.

- ^ "Government Accountability Office, p. 45" (PDF).

- ^ "Government Accountability Office, p. 46" (PDF).

- ^ "Government Accountability Office, p. 23" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Government Accountability Office, p. 22" (PDF).

- ^ a b c O'Keefe, Ed. "FBI J. Edgar Hoover Building 'Deteriorating,' Report Says." Washington Post. November 9, 2011. Accessed September 29, 2012.

- ^ "FBI's Growing Headquarters Needs Work, GAO Says." Federal Daily. November 9, 2011. Accessed September 29, 2012.

- ^ "Government Accountability Office, p. 8" (PDF).

- ^ "Government Accountability Office, p. 12" (PDF).

- ^ "Government Accountability Office, p. 36" (PDF).

- ^ Boxer, Barbara; Inhofe, James M. (December 8, 2014). "Committee Resolution: Federal Bureau of Investigation Consolidated Headquarters: National Capital Region" (PDF). United States Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works: 112th Congress, 1st Session. The Washington Post. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ^ Neibauer, Jonathan. "Fairfax Wants FBI For GSA Warehouse." Washington Business Journal. January 10, 2012. Accessed September 29, 2012.

- ^ Schumitz, Kali. "Fairfax Sets Its Sights on FBI Facility." Archived December 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Fairfax Times. November 29, 2012. Accessed December 1, 2012.

- ^ O'Connell, Jonathan (December 3, 2012). "GSA Proposes Trading Hoover Building for New FBI Campus". The Washington Post. Accessed December 3, 2012.

- ^ Spivack, Miranda S. and Zapana, Victor (December 21, 2012). "Montgomery Bids for New FBI Headquarters, to Dismay of Prince George's Officials". The Washington Post. Accessed December 22, 2012.

- ^ a b c Meyer, Eugene L. "Looking for New F.B.I. Headquarters, the Government Proposes a Trade". The New York Times. January 29, 2013. Accessed January 31, 2013.

- ^ a b c O'Connell, Jonathan. "FBI Lays Out What It Wants in a New Headquarters." The Washington Post. January 20, 2013. Accessed January 31, 2013.

- ^ The D.C. government has long wanted to take title to Poplar Point and turn it into a mixed-use development. However, in 2006, D.C. officials said they would no longer seek to obtain title to Poplar Point until the federal government replaced the aging Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge (also known as the South Capitol Street Bridge). In late December 2012, the city and federal officials announced a ,06 million project to replace and realign that bridge. See: Ackerman, Andrew. "D.C. Agency Plans to Issue Bonds to Redevelop Two Pieces of Land." The Bond Buyer. November 20, 2006; Halsey III, Ashley. "Decaying D.C. Bridge Reflects State of Thousands of Such Structures Nationwide." The Washington Post. December 31, 2012, accessed January 27, 2013; "Rebuilding Bridges in the District." The Washington Post. December 31, 2012, accessed 2013-01-27.

- ^ DeBonis, Mike. "City Will Study Fiscal Impacts of FBI Move." The Washington Post. February 26, 2013. Accessed February 27, 2013.

- ^ O'Connell, Jonathan. "Metro Proposes Land Deal to Lure FBI to Prince George's County." Washington Post. February 12, 2013, accessed February 13, 2013; Sernovitz, Daniel J. "Metro Land Deal for Greenbelt Metro Advances." Washington Business Journal. February 14, 2013, accessed 2013-02-14.

- ^ O'Connell, Jonathan. "Donald and Daughter Ivanka Trump Will Consider Acquiring FBI Headquarters." Washington Post. September 11, 2013. Accessed September 11, 2013.

- ^ a b c O'Connell, Jonathan. "General Services Administration Seeks 50 Acres for New FBI Headquarters Campus." Washington Post. November 15, 2013. Accessed November 16, 2013.

- ^ O'Connell, Jonathan. "D.C. Official Says GSA Criteria Renders District 'Effectively Ineligible' to Retain FBI HQ." Washington Post. December 5, 2013. Accessed December 5, 2013.

- ^ "Virginia politicians pressing for FBI headquarters in Springfield". The Washington Post. December 9, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ O'Connell, Johnathan (July 29, 2014). "List narrows for future FBI headquarters: Greenbelt, Landover or Springfield". Washington Post. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ^ Wright, Mina (September 3, 2014), "Notice of Intent To Prepare an Environmental Impact Statement for the Proposed Federal Bureau of Investigation Headquarters Consolidation and Exchange of the J. Edgar Hoover Building", Federal Register, vol. 79 (published September 8, 2014), pp. 53197–53198, retrieved September 30, 2014

- ^ "GSA Seeks Public Comment on Environmental Impact Statement for Consolidated FBI Headquarters". Washington, D.C.: General Services Administration. September 9, 2014. Archived from the original on September 30, 2014. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ^ "FBI HQ Consolidation: NEPA Public Engagement". Washington, DC: General Services Administration. September 23, 2014. Archived from the original on September 30, 2014. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ^ a b c Scott Baltic, FBI HQ Relocation to Be Announced by Year-End, Commercial Property Executive (October 4, 2016).

- ^ "Read the Democrats' letter and emails about President Trump and the FBI building | CNN Politics". CNN. October 18, 2018.

- ^ Bazail-Eimil, Eric (November 9, 2023). "FBI director, Virginia officials call for reversal of decision to relocate FBI headquarters in Maryland". POLITICO. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ^ Dil, Cuneyt (March 18, 2024). "New FBI headquarters gets funding momentum". Axios.

- ^ "New FBI headquarters will take more than a decade to build, as agency struggles with 'obsolete' space". federalnewsnetwork.com. April 11, 2024. Retrieved July 24, 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bednar, Michael J. L'Enfant's Legacy: Public Open Spaces in Washington. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- Glazer, Nathan. From a Cause to a Style: Modernist Architecture's Encounter With the American City. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Government Accountability Office. Federal Bureau of Investigation: Actions Needed to Document Security Decisions and Address Issues with Condition of Headquarters Buildings. GAO-12-96. Washington, D.C.: Government Accountability Office, November 2011.

- Gutheim, Frederick Albert and Lee, Antoinette Josephine. Worthy of the Nation: Washington, DC, From L'Enfant to the National Capital Planning Commission. 2d ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- Hess, Stephen. "The Federal Executive." In Daniel Patrick Moynihan: The Intellectual in Public Life. Robert A. Katzmann, ed. 2d ed. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2004.

- Hodgson, Godfrey. The Gentleman From New York: Daniel Patrick Moynihan: A Biography. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2000.

- Kohler, Susan A. The Commission of Fine Arts: A Brief History, 1910–1995. Washington, D.C.: Commission of Fine Arts, 1996.

- Legislative Reference Service. Digest of Public General Bills and Resolutions. Part 1. Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1972.

- Moeller, Gerard Martin and Weeks, Christopher. AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D.C. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- Peck, Robert A. "Daniel Patrick Moynihan and the Fall and Rise of Public Works." In Daniel Patrick Moynihan: The Intellectual in Public Life. Robert A. Katzmann, ed. 2d ed. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2004.

- Schellenberg, James A. Searchers, Seers, & Shakers: Masters of Social Science. New York: Transaction Publishers, 2007.

- Schrag, Zachary M. The Great Society Subway: A History of the Washington Metro. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- Scientific and Technical Information Office. Astronautics and Aeronautics, 1972: Chronology on Science Technology and Policy. Science and Technology Division, National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress/NASA, 1974.

- Theoharis, Athan G. The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999.

- United States Statutes At Large. Volume 86. Office of the Federal Register. Washington, D.C.: U.S. government Printing Office, 1973.

- Weeks, Christopher. AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994.

External links

[edit]- 1975 establishments in Washington, D.C.

- Brutalist architecture in Washington, D.C.

- Buildings of the United States government in Washington, D.C.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Government buildings completed in 1975

- Intelligence agency headquarters in the United States

- Landmarks in Washington, D.C.

- Office buildings in Washington, D.C.

- Buildings and structures in Penn Quarter

- Pennsylvania Avenue

- Police headquarters