Corps de ballet

In ballet, the corps de ballet ([kɔʁ də balɛ]; French for "body of the little dance") is the group of dancers who are not principal dancers or soloists. They are a permanent part of the ballet company and often work as a backdrop for the principal dancers.

A corps de ballet works as one, with synchronized movements and corresponding positioning on the stage. Well-known uses of the corps de ballet include the titular swans of Swan Lake and The Nutcracker's snow scene and the Waltz of the Flowers sequence.

Function

[edit]The corps de ballet sets the mood, scene, and nuance of the ballet, builds connection and camaraderie among the members of a ballet company, and creates large stage pictures through ensemble movement an choreography.[1]

The corps de ballet is to a dance troupe as the spine is to the body: It provides framework, support, context, and aesthetic form. - Dance Magazine[2]

Beyond the physical world-building provided by the corps de ballet, it also serves as a vital stepping stone for younger, incoming dancers, where they learn about company life and the structure of classical ballets before possibly being promoted to perform as a soloist or principal.[1]

History

[edit]Some scholars argue the nineteenth-century corps de ballet finds its roots in French revolutionary choral festivities, themselves rooted in festivals from antiquity.[3]

"Le petit rats"

[edit]

Dancers who filled out the Paris Opéra's corps de ballet often included pupils, some as young as 14, affectionately known as les rats or les petit rats.[4] Many etymological explanations exist for the term; among them Emile Littré's suggestion that the term "demoiselles d'opéra" (young lady of the opera) had been shortened simply to "ra", or the belief that the sound the corps de ballet's pointe shoes made on the wooden floors of the rehearsal rooms may be likened to the skittering of rats.[4]

In 1866, Théophile Gautier (author of Giselle), published an essay entitled Le Rat, a fond and humorous description of the habits of these young dancers.[4]

The rat, despite its masculine name ['rat' is a masculine noun in French], is an eminently feminine creature. You will only find them at the Rue le Peletier, at the Royal Academy of Music, or in the Rue Richer, at dance classes; they only exist there; you would search in vain anywhere else in the world. Paris possesses three things that all other capitals envy: the urchin, the grisette and the rat. The rat is a theatre urchin who has all the faults of the street urchin, fewer good qualities, and like the latter is a product of the July Revolution. Rat is what we, at the Paris Opera, call the young girls who are training to become dancers, and who appear in the crowd scenes, the backgrounds, the flights, the set pieces and other situations where their size can be excused by a limited view. The age of the rat varies from eight to fourteen or fifteen; a sixteen year-old rat is a very old rat, a horned rat, a white rat; this is as old as they ever get; at this age their studies are more or less finished, they have had a debut, danced a solo, their name has appeared in capitals on a poster; they have graduated as a 'tiger' and now become first, second, or third class ballerinas or member of the chorus, according to their merits or their patrons.[5]

The role of the corps during the late 1800s at the Paris Opéra Ballet could also include an underside. The foyer de la danse where dancers warmed up before performances also functioned as a kind of men's club, where wealthy male opera subscribers (abonnés) could conduct business, socialize, and proposition the ballerinas. Because many "petit rats" came from working-class backgrounds, and due to the power structures in place, they would have had financial and career incentive to submit to the affections and propositions of these subscribers.[6] However, little surviving contemporary writing on the subject chronicles the experiences or perspectives of le petit rats themselves, often erring instead on the side of gossip.[7]

20th century and beyond

[edit]Ballets like Flames of Paris, which featured an enormous corps of 24-32 dancers, pioneered an active use of the corps de ballet in storytelling.

Throughout the 21st century, the demands on corps dancers have changed, calling for them to be "more versatile and virtuosic as individuals" and causing them to "face more emotional and physical challenges than ever, amplified by heavy work schedules".[2] They are typically among the lowest-paid members of the company, and often not guaranteed year-round employment.[2] Despite the challenges, many corps dancers feel pride and connection with their positions in the corps: as Karin Ellis-Wentz, a now-retired dancer and faculty member at the Joffrey Ballet put it, "people need to know that you can have a fabulous career and stay in the corps."[2]

In media

[edit]

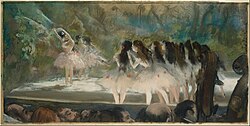

Impressionist painter Edgar Degas often featured the dancers of the Paris Opera Ballet in his works, among them some of his most well-known. In total, approximately 1,500 of his paintings, monotypes, and drawings are dedicated to the ballet, as well as some sculpture.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Hatch, Alex Marshall (7 October 2022). "5 Reasons to Love the Corps de Ballet". Pointe Magazine.

- ^ a b c d Carman, Joseph (24 July 2007). "The Silent Majority: Surviving and Thriving in the Corps de Ballet". Dance Magazine. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Macintosh, Fiona; et al. (19 September 2013). "17". Choruses, Ancient and Modern. Oxford University Press. pp. 309–326. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199670574.003.0018. ISBN 9780191759086. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ a b c "Petit Rat". Opéra national de Paris. Retrieved 2023-06-24.

- ^ Zanotti, Marisa. "The Rats: The Dancers of the Corps-de-Ballet". Glitch/Giselle. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ a b Fiore, Julia (6 January 2021). "The sordid truth behind Degas' ballet dancers". CNN. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Coons, Lorraine (2014). "Artiste or coquette? Les petits rats of the Paris Opera ballet". French Cultural Studies. 25 (2): 140–164. doi:10.1177/0957155814520912. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- Grant, Gail (1982) [1950]. Technical Manual and Dictionary of Classical Ballet (3rd ed.). New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-21843-0.