Yamatai

Yamatai Yamatai-koku (邪馬台国) | |

|---|---|

| c. 1st century–c. 3rd century | |

| Capital | Yamato |

| Common languages | Proto-Japonic |

| Government | Monarchy |

| King/Queen | |

• c. 180–c. 248 AD | Queen Himiko |

• c. 248 AD | Unknown king |

• c. 248–? AD | Queen Toyo |

| History | |

• Established | c. 1st century |

• Disestablished | c. 3rd century |

Yamatai or Yamatai-koku (邪馬台国) (c. 1st century – c. 3rd century) is the Sino-Japanese name of an ancient country in Wa (Japan) during the late Yayoi period (c. 1,000 BCE – c. 300 CE). The Chinese text Records of the Three Kingdoms first recorded the name as /*ja-maB-də̂/ (邪馬臺)[1] or /*ja-maB-ʔit/ (邪馬壹) (using reconstructed Eastern Han Chinese pronunciations)[1][2] followed by the character 國 for "country", describing the place as the domain of Priest-Queen Himiko (卑弥呼) (died c. 248 CE). Generations of Japanese historians, linguists, and archeologists have debated where Yamatai was located and whether it was related to the later Yamato (大和国).[3][4][5]

Chinese texts

[edit]

The oldest accounts of Yamatai are found in the official Chinese dynastic Twenty-Four Histories for the 1st- and 2nd-century Eastern Han dynasty, the 3rd-century Wei kingdom, and the 6th-century Sui dynasty.

The c. 297 CE Records of Wèi (traditional Chinese: 魏志), which is part of the Records of the Three Kingdoms (三國志), first mentions the country Yamatai, usually spelled as 邪馬臺 (/*ja-maB-də̂/), written instead with the spelling 邪馬壹 (/*ja-maB-ʔit/), or Yamaichi in modern Japanese pronunciation.[3]

Most Wei Zhi commentators accept the 邪馬臺 (/*ja-maB-də̂/) transcription in later texts and dismiss this initial spelling using 壹 (/ʔit/) meaning "one" (the anti-fraud character variant for 一 'one') as a miscopy, or perhaps a naming taboo avoidance, of 臺 (/dʌi/) meaning "platform; terrace." This history describes ancient Wa based upon detailed reports of 3rd-century Chinese envoys who traveled throughout the Japanese archipelago:

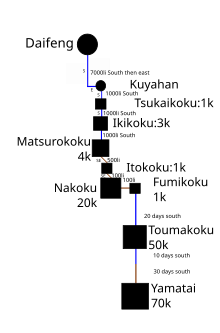

Going south by water for twenty days, one comes to the country of Toma, where the official is called mimi and his lieutenant, miminari. Here there are about fifty thousand households. Then going toward the south, one arrives at the country of Yamadai, where a Queen holds her court. [This journey] takes ten days by water and one month by land. Among the officials there are the ikima and, next in rank, the mimasho; then the mimagushi, then the nakato. There are probably more than seventy thousands households. (115, tr. Tsunoda 1951:9)

The Wei Zhi also records that in 238 CE, Queen Himiko sent an envoy to the court of Wei emperor Cao Rui, who responded favorably:[3]

We confer upon you, therefore, the title 'Queen of Wa Friendly to Wei', together with the decoration of the gold seal with purple ribbon. ...As a special gift, we bestow upon you three pieces of blue brocade with interwoven characters, five pieces of tapestry with delicate floral designs, fifty lengths of white silk, eight taels of gold, two swords five feet long, one hundred bronze mirrors, and fifty catties each of jade and of red beads. (tr. Tsunoda 1951:14-15)

The ca. 432 CE Book of the Later Han (traditional Chinese: 後漢書) says the Wa kings lived in the country of Yamatai (邪馬臺國):[4]

The Wa dwell on mountainous islands southeast of Han [Korea] in the middle of the ocean, forming more than one hundred communities. From the time of the overthrow of Chaoxian [northern Korea] by Emperor Wu (B.C. 140-87), nearly thirty of these communities have held intercourse with the Han [dynasty] court by envoys or scribes. Each community has its king, whose office is hereditary. The King of Great Wa [Yamato] resides in the country of Yamadai. (tr. Tsunoda 1951:1)

The Book of Sui (traditional Chinese: 隋書), finished in 636 CE, records changing the capital's name from the Yamatai recorded in the Book of Wei, to Yamadai (traditional Chinese: 邪靡堆, Middle Chinese: /jia muɑ tuʌi/; interpreted as Yamato (Japanese logographic spelling 大和):

Wa is situated in the middle of the great ocean southeast of Baekje and Silla, three thousand li away by water and land. The people dwell on mountainous islands. ...The capital is Yamadai, known in the Wei history as Yamatai. The old records say that it is altogether twelve thousand li distant from the borders of Lelang and Daifang prefectures, and is situated east of Kuaiji and close to Dan'er. (倭國在百濟・新羅東南、水陸三千里、於大海之中、依山島而居。... 都於邪靡堆、則魏志所謂邪馬臺者也。古云、去樂浪郡境及帶方郡並一萬二千里、在會稽之東、與儋耳相近。) (81, tr. Tsunoda 1951:28)

The History of the Northern Dynasties, completed 643-659 CE, contains a similar record, but transliterates the name Yamadai using a different character with a similar pronunciation (traditional Chinese: 邪摩堆).

Japanese texts

[edit]The first Japanese books, such as the Kojiki or Nihon Shoki, were mainly written in a variant of Classical Chinese called kanbun. The first texts actually in the Japanese language used Chinese characters, called kanji in Japanese, for their phonetic values. This usage is first seen in the 400s or 500s to spell out Japanese names, as on the Eta Funayama Sword or the Inariyama Sword. This gradually formalized over the 600s and 700s into the Man'yōgana system, a rebus-like transcription that uses specific kanji to represent Japanese phonemes. For instance, man'yōgana spells the Japanese mora ka using (among others) the character 加, which means "to add", and was pronounced as /kˠa/ in Middle Chinese and adopted into Japanese with the pronunciation ka. Irregularities within this awkward system led Japanese scribes to develop phonetically regular syllabaries. The new kana were graphic simplifications of Chinese characters. For instance, ka is written か in hiragana and カ in katakana, both of which derive from the Man'yōgana 加 character (hiragana from the cursive form of the kanji, and katakana from a simplification of the kanji).

The c. 712 Kojiki (古事記, "Records of Ancient Matters") is the oldest extant book written in Japan. The "Birth of the Eight Islands" section phonetically transcribes Yamato as 夜麻登, pronounced in Middle Chinese as /jiaH mˠa təŋ/ and used to represent the Old Japanese morae ya ma to2 (see also Man'yōgana#chartable). The Kojiki records the Shintoist creation myth that the god Izanagi and the goddess Izanami gave birth to the Ōyashima (大八州, "Eight Great Islands") of Japan, the last of which was Yamato:

Next they gave birth to Great-Yamato-the-Luxuriant-Island-of-the-Dragon-Fly, another name for which is Heavenly-August-Sky-Luxuriant-Dragon-Fly-Lord-Youth. The name of "Land-of-the-Eight-Great-Islands" therefore originated in these eight islands having been born first. (tr. Chamberlain 1919:23)

Chamberlain (1919:27) notes this poetic name "Island of the Dragon-fly" is associated with legendary Emperor Jimmu, whose honorific name includes "Yamato", as Kamu-yamato Iware-biko.

The 720 Nihon Shoki (日本書紀, "Chronicles of Japan") transcribes Yamato with the Chinese characters 耶麻騰, pronounced in Middle Chinese as /jia mˠa dəŋ/ and in Old Japanese as ya ma to2 or ya ma do2. In this version of the Eight Great Islands myth, Yamato is born second instead of eighth:

Now when the time of birth arrived, first of all the island of Ahaji was reckoned as the placenta, and their minds took no pleasure in it. Therefore it received the name of Ahaji no Shima. Next there was produced the island of Oho-yamato no Toyo-aki-tsu-shima. (tr. Aston 1924 1:13)

The translator Aston notes a literal meaning for the epithet of Toyo-aki-tsu-shima of "rich harvest's" (or "rich autumn's") "island" (i.e. "Island of Bountiful Harvests" or "Island of Bountiful Autumn").

The c. 600-759 Man'yōshū (万葉集, "Myriad Leaves Collection") transcribes various pieces of text using not the phonetic man'yōgana spellings, but rather a logographic style of spelling, based on the pronunciation of the kanji using the native Japanese vocabulary of the same meaning. For instance, the name Yamato is sometimes spelled as 山 (yama, "mountain") + 蹟 (ato, "footprint; track; trace"). Old Japanese pronunciation rules caused the sound yama ato to contract to just yamato.

Government

[edit]According to the Chinese record Twenty-Four Histories, Yamatai was originally ruled by the shamaness Queen Himiko. The other officials of the country were also ranked under the queen, with the highest position called ikima, followed by mimasho, then mimagushi, and the lowest-ranking position of nakato. According to the legends, Himiko lived in a palace with 1,000 female handmaidens and one male servant who would feed her. This palace was most likely located at the site of Makimuku in Nara prefecture. She ruled for most of the known history of Yamatai.

After Queen Himiko died, an unknown king became ruler of the country for a short period, and then Queen Toyo reigned before Yamatai disappears from historical records.

According to Japanese historian Wakai Toshiaki (若井敏明), the Yamato Kingship collapsed Yamatai in 367, killing its last ruler, Queen Taburatsuhime (田油津媛).[6]

Pronunciations

[edit]Modern Japanese Yamato (大和) descends from Old Japanese Yamatö or Yamato2, which has been associated with Yamatai. The latter umlaut or subscript diacritics distinguish two vocalic types within the proposed eight vowels of Nara period (710-794) Old Japanese (a, i, ï, u, e, ë, o, and ö, see Jōdai Tokushu Kanazukai), which merged into the five modern vowels (a, i, u, e, and o).

During the Kofun period (250-538) when kanji were first used in Japan, Yamatö was written with the ateji 倭 for Wa, the name given to "Japan" by Chinese writers using a character meaning "docile, submissive". During the Asuka period (538-710) when Japanese place names were standardized into two-character compounds, the spelling of Yamato was changed to 大倭, adding the prefix 大 ("big; great").

Following the ca. 757 graphic substitution of 和 ("peaceful") for 倭 ("docile"), the name Yamato was spelled 大和 ("great harmony"), using the Classical Chinese expression 大和 (pronounced in Middle Chinese as /dɑH ɦuɑ/, as used in Yijing 1, tr. Wilhelm 1967:371: "each thing receives its true nature and destiny and comes into permanent accord with the Great Harmony.")

The early Japanese texts above give three spellings of Yamato in kanji: 夜麻登 (Kojiki), 耶麻騰 (Nihon Shoki), and 山蹟 (Man'yōshū). The Kojiki and Nihon Shoki use Sino-Japanese on'yomi readings of ya 夜 "night" or ya or ja 耶 (an interrogative sentence-final particle in Chinese), ma 麻 "hemp", and to 登 "rise; mount" or do 騰 "fly; gallop". In contrast, the Man'yōshū uses Japanese kun'yomi readings of yama 山 "mountain" and ato 跡 "track; trace". As noted further above, Old Japanese pronunciation rules caused yama ato to contract to yamato.

The early Chinese histories above give three transcriptions of Yamatai: 邪馬壹 (Wei Zhi), 邪馬臺 (Hou Han Shu), and 邪摩堆 (Sui Shu). The first syllable is consistently written with 邪 "a place name", which was used as a jiajie graphic-loan character for 耶, an interrogative sentence-final particle, and for 邪 "evil; depraved". The second syllable is written with 馬 "horse" or 摩 "rub; friction". The third syllable of Yamatai is written in one variant with 壹 "faithful, committed", which is also financial form of 一, "one", and more commonly using 臺 "platform; terrace" (cf. Taiwan 臺灣) or 堆 "pile; heap". Concerning the transcriptional difference between the 邪馬壹 spelling in the Wei Zhi and the 邪馬臺 in the Hou Han Shu, Hong (1994:248-9) cites Furuta Takehiko that 邪馬壹 was correct. Chen Shou, author of the ca. 297 Wei Zhi, was writing about recent history based on personal observations; Fan Ye, author of the ca. 432 Hou Han Shu, was writing about earlier events based on written sources. Hong says the San Guo Zhi uses 壹 ("one") 86 times and 臺 ("platform") 56 times, without confusing them.

During the Wei period, 臺 was one of their most sacred words, implying a religious-political sanctuary or the emperor's palace. The characters 邪 and 馬 mean "evil; depraved" and "horse", reflecting the contempt Chinese felt for a barbarian country, and it is most unlikely that Chen Shou would have used a sacred word after these two characters. It is equally unlikely that a copyist could have confused the characters, because in their old form they do not look nearly as similar as in their modern printed form. Yamadai was Fan Yeh's creation. (1994:249)

He additionally cites Furuta that the Wei Zhi, Hou Han Shu, and Xin Tang Shu histories use at least 10 Chinese characters to transcribe Japanese to, but 臺 is not one of them.

In historical Chinese phonology, the Modern Chinese pronunciations differ considerably from the original 3rd-7th century transcriptions from a transitional period between Archaic or Old Chinese and Ancient or Middle Chinese. The table below contrasts Modern pronunciations (in Pinyin) with differing reconstructions of Early Middle Chinese (Edwin G. Pulleyblank 1991), "Archaic" Chinese (Bernhard Karlgren 1957), and Middle Chinese (William H. Baxter 1992). Note that Karlgren's "Archaic" is equivalent with "Middle" Chinese, and his "yod" palatal approximant i̯ (which some browsers cannot display) is replaced with the customary IPA j.

| Characters | Mandarin Chinese | Middle Chinese | Early Middle Chinese | "Archaic" Chinese |

| 邪馬臺 | yémǎtái | yæmæXdoj | jiamaɨ'dəj | jama:t'ḁ̂i |

| 邪摩堆 | yémóduī | yæmatwoj | jiamatwəj | jamuâtuḁ̂i |

| 大和 | dàhé | dajHhwaH | dajhɣwah | d'âiɣuâ |

Roy Andrew Miller describes the phonological gap between these Middle Chinese reconstructions and the Old Japanese Yamatö.

The Wei chih account of the Wo people is chiefly concerned with a kingdom which it calls Yeh-ma-t'ai, Middle Chinese i̯a-ma-t'ḁ̂i, which inevitably seems to be a transcription of some early linguistic form allied with the word Yamato. The phonology of this identification raises problems which after generations of study have yet to be settled. The final -ḁ̂i of the Middle Chinese form seems to be a transcription of some early form not otherwise recorded for the final -ö of Yamato. (1967:17-18)

While most scholars interpret 邪馬臺 as a transcription of pre-Old Japanese yamatai, Miyake (2003:41) cites Alexander Vovin that Late Old Chinese ʑ(h)a maaʳq dhəə 邪馬臺 represents a pre-Old Japanese form of Old Japanese yamato2 (*yamatə). Tōdō Akiyasu reconstructs two pronunciations for 䑓 – dai < Middle dǝi < Old *dǝg and yi < yiei < *d̥iǝg – and reads 邪馬臺 as Yamai.[citation needed]

The etymology of Yamato, like those of many Japanese words, remains uncertain. While scholars generally agree that Yama- signifies Japan's numerous yama 山 "mountains", they disagree whether -to < -tö signifies 跡 "track; trace", 門 "gate; door", 戸 "door", 都 "city; capital", or perhaps 所 "place". Bentley (2008) reconstructs underlying Wa's endonym *yama-tǝ(ɨ) as underlying the transcription 邪馬臺's pronunciation *ja-maˀ-dǝ > *-dǝɨ.[7]

Location

[edit]

The location of Yamatai-koku is one of the most contentious topics in Japanese history. Generations of historians have debated "the Yamatai controversy" and have hypothesized numerous localities, some of which are fanciful like Okinawa (Farris 1998:245). General consensus centers around two likely locations of Yamatai, either northern Kyūshū or Yamato Province in the Kinki region of central Honshū. Imamura describes the controversy.

The question of whether the Yamatai Kingdom was located in northern Kyushu or central Kinki prompted the greatest debate over the ancient history of Japan. This debate originated from a puzzling account of the itinerary from Korea to Yamatai in Wei-shu. The northern Kyushu theory doubts the description of distance and the central Kinki theory the direction. This has been a continuing debate over the past 200 years, involving not only professional historians, archeologists and ethnologists, but also many amateurs, and thousands of books and papers have been published. (1996:188)

The location of ancient Yamatai-koku and its relation with the subsequent Kofun-era Yamato polity remains uncertain. In 1989, archeologists discovered a giant Yayoi-era complex at the Yoshinogari site in Saga Prefecture, which was thought to be a possible candidate for the location of Yamatai. While some scholars, most notably Seijo University historian Takehiko Yoshida, interpret Yoshinogari as evidence for the Kyūshū Theory, many others support the Kinki Theory based on Yoshinogari clay vessels and the early development of Kofun (Saeki 2006).

The recent archeological discovery of a large stilt house suggests that Yamatai-koku was located near Makimuku in Sakurai, Nara (Anno. 2009). Makimuku has also revealed wooden tools such as masks and a shield fragment. A large amount of pollen that would have been used to dye clothes was also found at the site of Makimuku. Clay pots and vases were also found at the site of Makimuku similar to ones found in other prefectures of Japan. Another site at Makimuku supporting the theory that Yamatai once existed there is, the possible burial site of Queen Himiko at the Hashihaka burial mound. Himiko was the ruler of Yamatai from c. 180 C.E.- c. 248 C.E.

In popular culture

[edit]- Yamatai, depicted as an isolated island somewhere in the Pacific, is the setting of the 2013 video game Tomb Raider and its 2018 film adaptation. Queen Himiko is a key part of the plot.[8]

- Yamatai appears as historic setting 1990's video game, Legend of Himiko.

- Yamatai and its queen Himiko are the main villains in the Steel Jeeg anime series.

- Yamtaikoku is the setting of the 2020/22 limited time event of the mobile game Fate/Grand Order, prominently featuring Queen Himiko.[9]

- Queen Himiko and the Yamatai Kingdom are the subjects of the song "Himiko" by Japanese EDM group Wednesday Campanella.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Schuessler, Axel (2014). "Phonological Notes on Hàn Period Transcriptions of Foreign Names and Words" in Studies in Chinese and Sino-Tibetan Linguistics: Dialect, Phonology, Transcription and Text. Series: Language and Linguistics Monograph Series. 53 Ed. VanNess Simmons, Richard & Van Auken, Newell Ann. Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan. p. 255, 286

- ^ Schuessler, Axel (2009). Minimal Old Chinese and Later Han Chinese. University of Hawaii Press. p. 298, 299

- ^ a b c Sansom, George Bailey (1958). A history of Japan to 1334. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. pp. 14–16. ISBN 0-8047-0522-4. OCLC 36820223.

- ^ a b Delmer M. Brown, ed. (1988–1999). The Cambridge history of Japan. Vol. 1. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 22. ISBN 0-521-22352-0. OCLC 17483588.

- ^ Huffman, James L. (2010). Japan in world history. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 6–11. ISBN 978-0-19-536808-6. OCLC 323161049.

- ^ 若井敏明 (2010). 邪馬台国の滅亡: 大和王権の征服戦争 (in Japanese). 吉川弘文館. ISBN 978-4-642-05694-6.

- ^ Bentley, John (2008). "The Search for the Language of Yamatai" in Japanese Language and Literature , 42.1, p. 11 of pp. 1-43.

- ^ Pinchefsky, Carol (March 12, 2013). "A Feminist Reviews Tomb Raider's Lara Croft". Forbes.

- ^ "Super Ancient Shinsengumi History GUDAGUDA Yamataikoku 2022".

- ^ "Wednesday Campanella has released the music video for "Himiko," in which Utaha becomes a weather caster and predicts heavy rain".

Sources

[edit]- "Remains of what appears to be Queen Himiko's palace found in Nara", The Japan Times, Nov 11, 2009.

- Aston, William G, tr. 1924. Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to AD 697. 2 vols. Charles E Tuttle reprint 1972.

- Baxter, William H. 1992. A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology. Mouton de Gruyter.

- Chamberlain, Basil Hall, tr. 1919. The Kojiki, Records of Ancient Matters. Charles E Tuttle reprint 1981.

- Edwards, Walter. 1998. "Mirrors to Japanese History", Archeology 51.3.

- Farris, William Wayne. 1998. Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan. University of Hawaiʻi Press.

- Hall, John Whitney. 1988. The Cambridge History of Japan: Volume 1, Ancient Japan. Cambridge University Press.

- Hérail, Francine (1986), Histoire du Japon – des origines à la fin de Meiji [History of Japan – from origins to the end of Meiji] (in French), Publications orientalistes de France.

- Hong, Wontack. 1994. Paekche of Korea and the Origin of Yamato Japan. Kudara International.

- Imamura. Keiji. 1996. Prehistoric Japan: New Perspectives on Insular East Asia. University of Hawaiʻi Press.

- Karlgren, Bernhard. 1957. Grammata Serica Recensa. Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities.

- Kidder, Jonathan Edward. 2007. Himiko and Japan's Elusive Chiefdom of Yamatai. University of Hawaiʻi Press.

- McCullough, Helen Craig. 1985. Brocade by Night: 'Kokin Wakashū' and the Court Style in Japanese Classical Poetry. Stanford University Press.

- Miller, Roy Andrew. 1967. The Japanese Language. University of Chicago Press.

- Miyake, Marc Hideo. 2003. Old Japanese: A Phonetic Reconstruction. Routledge Curzon.

- Philippi, Donald L. (tr.) 1968. Kojiki. University of Tokyo Press.

- Pulleyblank, EG. 1991. "Lexicon of Reconstructed Pronunciation in Early Middle Chinese, Late Middle Chinese, and Early Mandarin". UBC Press.

- Saeki, Arikiyo (2006), 邪馬台国論争 [Yamataikoku ronsō] (in Japanese), Iwanami, ISBN 4-00-430990-5.

- Goodrich, Carrington C, ed. (1951), Japan in the Chinese Dynastic Histories: Later Han Through Ming Dynasties, translated by Tsunoda, Ryusaku, South Pasadena, CA: PD & Ione Perkins.

- Wang Zhenping. 2005. Ambassadors from the Islands of Immortals: China-Japan Relations in the Han-Tang Period. University of Hawaiʻi Press.

- Hakkutsu sareta Nihon rett, 2010. Makimuku: were the huge buildings, neatly lined up, a palace? A discovery enlivens debate over the country Yamatai''.