Naqada culture

Extent of Naqada I culture | |

| Geographical range | Egypt |

|---|---|

| Period | Neolithic |

| Dates | c. 4000–3000 BC |

| Type site | Naqada |

| Preceded by | Badarian culture |

| Followed by | Protodynastic Period |

| Chalcolithic Eneolithic, Aeneolithic, or Copper Age |

|---|

|

↑ Stone Age ↑ Neolithic |

|

↓ Bronze Age ↓ Iron Age |

25°57′00″N 32°44′00″E / 25.95000°N 32.73333°E The Naqada culture is an archaeological culture of Chalcolithic Predynastic Egypt (c. 4000–3000 BC), named for the town of Naqada, Qena Governorate. A 2013 Oxford University radiocarbon dating study of the Predynastic period suggests a beginning date sometime between 3,800 and 3,700 BC.[1]

The final phase of the Naqada culture is Naqada III, which is coterminous with the Protodynastic Period (Early Bronze Age c. 3200–3000 BC) in ancient Egypt.

Chronology

William Flinders Petrie

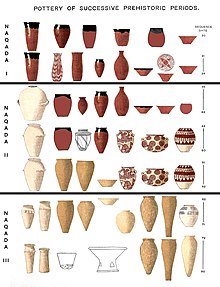

The Naqada period was first divided by the British Egyptologist William Matthew Flinders Petrie, who explored the site in 1894, into three sub-periods:

- Naqada I: Amratian (after the cemetery near El-Amrah, Egypt)

- Naqada II: Gerzean (after the cemetery near Gerzeh)

- Naqada III: Semainean (after the cemetery near Es-Semaina)

Werner Kaiser

Petrie's chronology was superseded by that of Werner Kaiser in 1957. Kaiser's chronology began c. 4000 BC, but the modern version has been adjusted slightly, as follows:[2]

- Naqada I (about 3900–3650 BC)

- black-topped and painted pottery

- trade with Nubia, Western Desert oases, and Eastern Mediterranean[3]

- obsidian from Ethiopia[4]

- Naqada II (about 3650–3300 BC)

- represented throughout Egypt

- first marl pottery, and metalworking

- Naqada III (about 3300–2900 BC)

- more elaborate grave goods, first Pharaohs

- cylindrical jars

- writing

-

Figure of a woman. Naqada II period, 3500–3400 BCE. Brooklyn Museum

-

Pre-dynastic Naqada cooking pot - scientific analysis has shown that this pot once contained a meat stew with honey

-

Incised hippopotamus ivory tusk, an upper canine with four holes around top, from Naqada Tomb 1419, Egypt, Naqada period, The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

-

Spatha shell from Naqada tomb 1539, Egypt, Naqada I period, The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

-

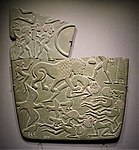

Bull Palette

-

The Battlefield Palette, 3100 B.C.

Monuments and excavations

The Material culture at Naqada sites vary depending on the phase of Naqada Culture. The excavation of pottery at most Naqada sites with each distinct periods of culture having their own defining pottery. The types of pottery that were found at Naqada sites arranged from bowls, small jars, bottles, medium-sized neck jars to wine jars and wavy-handled jars. Most of the pottery excavated from Naqada sites have probably been used for cultural reasons (when having decorations on them) and for storage of food as well as the placing of food on them (for consumption). The various designs that are included in pottery have waves in them and are sometimes accompanied with floral motifs or drawings of people, suggesting that art was strongly expressed during Naqada Cultures.[8] These designs might have also had an early Mesopotamian influence as some animals depicted on pottery during the Naqada II period show griffins and serpent-headed panthers, which are linked to early Uruk period pottery.[9]

-

Naqada D-ware Jar

-

Vase, Amratian, Naqada I.jpg

-

Jar, Late Naqada II (3500-3330 BCE) from Egypt - in Metropolitan Museum

There is evidence that copper harpoons had been manufactured at various Naqada III sites such as Tel El-Farkha and Tel El-Murra. Copper Harpoons in Naqada society were primarily used for hunting Nile Fauna such as the Hippopotamus. The importance of hunting the Hippopotamus is noted to be important among Naqada high class as it was regarded as high social status although the access of copper was more open to the elites rather than the common folk. Harpoons themselves were likely used for protection of trade as evident from an Ancient Egyptian port that signaled that it was used by people of trade caravans as protection. Another use of the Harpoon was in Art as the symbolism of the Harpoon was probably used in religious purposes as possibly referencing a magic-like hunt using these weapons. [10] The small figurines that are found at Naqada type sites are usually made out of materials such as stones and Ivory. They may have been made for everyday use such as children toys or for ritualistic purpose such as for medicine and magic. The figurines may have also played more into religion as speculated that some figurines were made to be worshiped as Fertile idols and helping with the production of farming and crop use. The small figurines may have also been used in mortuary and burial rituals as excavated figurines at Naqada sites have been found close to bodies, suggesting that figurines may have been used in these rituals.[11]

-

Naqada bone figure of woman. British Museum

-

Tusk Figurine of a Man Late Naqada I. Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Figurines of bone and ivory. Predynastic, Naqada I. 4000-3600 BC

Knives and knife handles were common during Naqada Culture. There seems to be a distinct tradition of knife: the Twisted-knife tradition which started in Northern/Lower Egypt and made its way into upper Egypt combining Northern and Southern knife manufacturing styles.[12] The knives that were found during this period appeared to be made out of Flint. Knife handles that are dated back to the Naqada II period show intricate work on knife handles as designs of humans worshiping and scenes from the Nature of Egypt are shown on these knife handles. The knives that were used in Naqada society were used for everyday use such as for cutting food and for hunting and ritualistic purposes. Due to the artwork on some of the knife handles, it can be inferred that knives with designed handles on them were reserved for the upper elites of society.[13] Early forms of Egyptian writing appear in the Naqada culture. Writing itself appears around the Naqada II period and the forms that it took were in the forms of pictograms. There are several artifacts that depict writing on them. Mostly these are found on vessels and the writing usually depicts animals and people and was used to document trade and administrative transactions.[13] With writing being central around the Elites, early writing was used more for documentation of royalty more than everyday life in Naqada Culture as seen in Early Dynastic and Predynastic Egypt.[14]

-

Fishtail Knife dated to Naqada II period. Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

The Gebel el-Arak Knife. The reverse of the handle shows a Master of Animals motif: two confronted lions, flanking a central figure

-

The Gebel el-Arak Knife, Musée du Louvre (3300-3200 BCE).

Multiple buildings were present at Naqada sites. The site at Tel-El Farkha, located 14 km east from El-Simbillawein in Egypt, shows evidence of breweries is found dating back from the Naqada II site. The Breweries themselves were surrounded by wooden fences that would've separated ordinary houses from. The wooden fences themselves were replaced over time by mud brick walls as evident the excavation at Tel-El Farkha. The Brewery located at Tel-EL Farkha has 13 consecutive vats in the building which was probably used for the production of beer.[15] The Beer was usually made in two ways of making part of the grain malted and the other part into Porridge. Then it would be mixed and the liquid would be removed from the mixture via sieving the liquid. This resulted in Beer.[16] Also at the Tel-El Farkha sites is evidence of buildings one of the biggest in the site was built on top of a mound and is surrounded by thick mud brick walls and inside the building is small poorly preserved rooms that were surrounded by 30–40 cm walls. The walls that are made around the structure were probably made for defensive reasons. There have also been jars found in this specific building suggesting that the building was also used as a warehouse.[15] Predynastic Egyptians in the Naqada I period traded with Nubia to the south, the oases of the western desert to the west, and the cultures of the eastern Mediterranean to the east.[17] Trade was most likely conducted by the elites of society.[15] People of the Naqada culture traded with cultures in Lower Nubia most likely the A-culture group. Material evidence that's found of the trade between the Naqada cultures and Nubians is found in the artifacts that are at these sites. Items that are often traded between the two include pottery, clothing, palettes, and stone vessels were most likely exchanged between Nubians and Egyptians. The pottery that was found in Nubia was mostly found in grave sites usually around bodies.[8] Pottery itself was also traded from the Levant as one piece of pottery from the Tel-El Farkha site was found to have been made out of clay that isn't present in the region suggesting that it was made and traded from the Levant.[15] They also imported obsidian from Ethiopia to shape blades and other objects from flakes.[18] Charcoal samples found in the tombs of Nekhen, which were dated to the Naqada I and II periods, have been identified as cedar from Lebanon.[19]

-

Palette in the Shape of a Boat 3700-3600 BCE Naqada I Brooklyn Museum.

-

Double Bird-Head Palette & Fish Palette, Naqada II

Biological anthropological studies

In 1993 a craniofacial study was performed by the anthropologist C. Loring Brace, the report reached the view that "The Predynastic of Upper Egypt and the Late Dynastic of Lower Egypt are more closely related to each other than to any other population", and most similar to modern Egyptians among modern populations, stating "the Egyptians have been in place since back in the Pleistocene and have been largely unaffected by either invasions or migrations." The craniometric analysis of predynastic Naqada human remains found that they were closely related to other Afroasiatic-speaking populations inhabiting North Africa, parts of the Horn of Africa and the Maghreb, as well as to Bronze Age and medieval period Nubians and to specimens from ancient Jericho. The Naqada skeletons were also morphologically proximate to modern osteological series from Europe and the Indian subcontinent. However, the Naqada skeletons and these ancient and recent skeletons were phenotypically distinct from skeletons belonging to modern Niger-Congo-speaking populations inhabiting Sub-Saharan Africa and Tropical Africa, as well as from Mesolithic skeletons excavated at Wadi Halfa in the Nile Valley.[20]

In 2022, the methodology of the Brace study was criticised by biological anthropologist S.O.Y. Keita for "misstating the underlying assumptions of canonical variates and principal component analysis used in others' work". Also, Keita noted that the 1993 study overlooked "the fact that even in their study Egyptians could be found clustering with ancient Nubians and modern Somalis, both tropical African groups".[21]

Hanihara et al. (2003) performed a cranial study on 70 samples from a global database which featured samples from Predynastic Naqada and 12th-13th dynasty Kerma which were collectively classified in the study as "North Africans" and other samples from Somalia along with Nigeria which were classified as "Sub-Saharans", but lacked a specified dating period. The samples from predynastic Naqada and Kerma clustered closely and with European groups, whilst the other samples from Sub-Saharan Africa showed "significant separation from other regions, as well as diversity among themselves".[22]

On the other hand, various biological anthropological studies have found Naqada skeletal remains to have Northeastern African biological affinities.[23][24] In 1996, 53 Naqada crania were measured and characterized by SOY Keita. He concluded that 61-64% were classified as southern series (which shares closest affinities with Kerma Kushites), while 36-41% were more similar to the northern Egyptian pattern (Coastal Maghrebi). In contrast, the set of Badarian crania were largely conforming to the Upper Egyptian-southern series at rates of 90-100%, with 9% possibly displaying northern affinities. This change is mainly attributed to the local migration along the Nile-Valley from northern Egyptians, and/or migration of Near-East populations, which lead to genetic exchange. The Middle Eastern series had some similarities with the early Southern Upper Egyptians and Nubians, which was considered by the researcher probably a reflection of their real presence to some degree, a consideration attested by archeological and historical sources.[25]

The biological anthropologists, Shomarka Keita and A.J. Boyce, have stated that the "studies of crania from southern predynastic Egypt, from the formative period (4000-3100 B.C.), show them usually to be more similar to the crania of ancient Nubians, Kushites, Saharans, or modern groups from the Horn of Africa than to those of dynastic northern Egyptians or ancient or modern southern Europeans". Keita and Boyce further added that the limb proportions of early Nile Valley remains were generally closer to tropical populations. They regarded this as significant because Egypt is not located in the tropical region. The authors suggested that "the Egyptian Nile Valley was not primarily settled by cold-adapted peoples such as Europeans".[26]

In 1996, Lovell and Prowse reported the presence of individuals buried at Naqada in what they interpreted to be elite, high-status tombs, showing them to be an endogamous ruling or elite segment who were significantly different from individuals buried in two other, apparently nonelite cemeteries, and more closely related morphologically to populations in Northern Nubia (A-Group) than to neighbouring populations at Badari and Qena in southern Egypt. Specifically, the authors stated that the Naqada samples were "more similar to the Lower Nubian protodynastic sample than they are to the geographically more proximate Egyptian samples" in Qena and Badari. Although, the samples from Naqada, Badari and Qena were all found to be significantly different from each other and from the protodynastic populations in northern Nubia.[27] Overall, both the elite and nonelite individuals at the Naqada cemeteries were more similar to each other than they were to the samples in northern Nubia or to other predynastic samples in southern Egypt.[28]

In 1999, Lovell summarised the findings of modern skeletal studies which had determined that "in general, the inhabitants of Upper Egypt and Nubia had the greatest biological affinity to people of the Sahara and more southerly areas" but exhibited local variation in an African context. She also wrote that the archaeological and inscriptional evidence for contact between Egypt and Syro-Palestine "suggests that gene flow from these areas was very likely".[29]

In 2018, Godde assessed population relationships in the Nile Valley by comparing crania from 18 Egyptian and Nubian groups, spanning from Lower Egypt to Lower Nubia across 7,400 years. Overall, the results showed that the biological distance matrix demonstrates the smallest biological distances, which indicate a closer affiliation are between Kerma and Gizeh, as well as Kerma and Lisht. The greatest biological distances are assigned to Sayala C-Group and the Pan-Grave sample, along with Sayala C-Group and the Semna South Christian sample.[30] The earliest group, the Mesolithic, demonstrated smaller biological distances with Egyptian Naqada individuals than another Nubian group (Kulubnarti Island) and inline with the Nubian Christian group from Semna South. The northern Lower Nubia and Upper Egypt samples clustered together: A-Group, C-Group, Mesolithic, Sayala C-Group, Coptic, Hesa/ Biga, Badari, and Naqada. Second, the Lower Egypt samples (Gizeh, Cairo, and Lisht) formed a relatively homogeneous grouping. Finally, Semna South (Meroitic, X-Group, Christian), the geographically close Kulubnarti (Christian), Pan-Grave, and Kerma samples also plotted close together. In sum, there was a north–south gradient in the data set.[31]

In 2020, Godde analysed a series of crania, including two Egyptian (predynastic Badarian and Nagada series), a series of A-Group Nubians and a Bronze Age series from Lachish, Palestine. The two pre-dynastic series had strongest affinities, followed by closeness between the Nagada and the Nubian series. Further, the Nubian A-Group plotted nearer to the Egyptians and the Lachish sample placed more closely to Naqada than Badari. According to Godde the spatial-temporal model applied to the pattern of biological distances explains the more distant relationship of Badari to Lachish than Naqada to Lachish as gene flow will cause populations to become more similar over time. Overall, both Egyptian samples were more similar to the Nubian series than to the Lachish series.[32]

In 2023, Christopher Ehret reported that the physical anthropological findings from the "major burial sites of those founding locales of ancient Egypt in the fourth millennium BCE, notably El-Badari as well as Naqada, show no demographic indebtedness to the Levant". Ehret specified that these studies revealed cranial and dental affinities with "closest parallels" to other longtime populations in the surrounding areas of northeastern Africa "such as Nubia and the northern Horn of Africa". He further commented that "members of this population did not migrate from somewhere else but were descendants of the long-term inhabitants of these portions of Africa going back many millennia". Ehret also cited existing, archaeological, linguistic and genetic data which he argued supported the demographic history.[33]

Genetic data on Naqada remains

Several scholars have highlighted a number of methodological limitations with the application of DNA studies to Egyptian mummified remains.[34][35][33] Moreover, Keita and Boyce (1996) noted that DNA studies had not been conducted on the southern predynastic Egyptian skeletons.[36] According to historian William Stiebling and archaeologist Susan N. Helft, conflicting DNA analysis on Egyptian mummies has led to a lack of consensus on the genetic makeup of the ancient Egyptians and their geographic origins.[37]

Although, various DNA studies have found Christian-era and modern Nubians along with modern Afro-Asiatic speaking populations in the Horn of Africa to be descended from a mix of West Eurasian and East African populations.[38][39][40][41]

Relative chronology

See also

- Badarian culture

- Early Dynastic Egypt

- First Dynasty of Egypt

- List of Pharaohs

- Scorpion I

- Scorpion II

- Scorpion Macehead

References

- ^ "Carbon dating shows ancient Egypt's rapid expansion".

- ^ Hendrickx, Stan. "The relative chronology of the Naqada culture: Problems and possibilities". Academia. p. 64.

- ^ Shaw, Ian (2002). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 61. ISBN 0-500-05074-0.

- ^ Barbara G. Aston, James A. Harrell, Ian Shaw (2000). Paul T. Nicholson and Ian Shaw editors. "Stone," in Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology, Cambridge, 5-77, pp. 46-47. Also note: Barbara G. Aston (1994). "Ancient Egyptian Stone Vessels," Studien zur Archäologie und Geschichte Altägyptens 5, Heidelberg, pp. 23-26. (See on-line posts: [1] and [2].)

- ^ "UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology" (PDF).

- ^ "Naqada, ivory carvings". www.ucl.ac.uk.

- ^ Petrie, William Matthew Flinders (1895). Naqada and Ballas. p. 213.

- ^ a b Takamiya, Izumi H. (December 2004). "Egyptian Pottery Distribution in A-Group Cemeteries, Lower Nubia: Towards an Understanding of Exchange Systems between the Naqada Culture and the A-Group Culture". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 90 (1): 35–62. doi:10.1177/030751330409000103. ISSN 0307-5133. S2CID 191702457.

- ^ Joffe, Aleander J. (2000). "Egypt and Syro-Mesopotamia in the 4th millennium: implications of the new chronology". Current Anthropology. 1 (41): 113–123. doi:10.1086/300110. S2CID 11399314 – via University of Chicago Journals.

- ^ "Mining for ancient copper. Essays in memory of Beno Rothenberg | WorldCat.org". www.worldcat.org. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- ^ Ordynat, Ryna (2018-03-31). "Chapter 2:The Study of Predynastic Figurines". Egyptian Predynastic Anthropomorphic Objects: A Study of Their Function and Significance in Predynastic Burial Customs (1 ed.). Archaeopress. pp. 7–16.

- ^ Śliwa, Joachim (2014). "The Nile Delta as a Center of Cultural Interaction Between Upper Egypt and the Southern Levant in the 4th Millennium BC.". Studies in ancient art and civilization (18 ed.). Państw. Wydaw. Naukowe. pp. 25–45. ISBN 978-83-01-10282-1. OCLC 165389017.

- ^ a b Josephson, Jack A.; Dreyer, Gunter (2015). "Naqada IId: The Birth of an Empire Kingship, Writing, Organized Religion". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 51: 165–178. doi:10.5913/jarce.51.2015.a007 (inactive 1 November 2024) – via Academida.edu.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Bard, Kathryn A. (7 January 2015). An introduction to the archaeology of Ancient Egypt. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-89611-2. OCLC 1124521578.

- ^ a b c d Ciałowicz, Krzysztof Marek (2017-08-23). "New Discoveries at Tell el-Farkha and the Beginnings of the Egyptian State". Études et Travaux (30): 231. doi:10.12775/etudtrav.30.011. ISSN 2449-9579.

- ^ Adamski, Bartosz; Rosińska-Balik, Karolina (2014). "Brewing Technology in Early Egypt. Invention of Upper or Lower Egyptians?". Studies in African Archaeology (13): 23–36 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Shaw, Ian (2002). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 61. ISBN 0-500-05074-0.

- ^ Barbara G. Aston, James A. Harrell, Ian Shaw (2000). Paul T. Nicholson and Ian Shaw editors. "Stone," in Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology, Cambridge, 5-77, pp. 46-47. Also note: Barbara G. Aston (1994). "Ancient Egyptian Stone Vessels", Studien zur Archäologie und Geschichte Altägyptens 5, Heidelberg, pp. 23-26. See on-line posts: [3] and [4].

- ^ Parsons, Marie. "Egypt: Hierakonpolis, A Feature Tour Egypt Story". www.touregypt.net. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ^ Brace, C. Loring; et al. (1993). "Clines and clusters versus "race:" a test in ancient Egypt and the case of a death on the Nile". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 36 (S17): 1–31. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330360603. Retrieved 1 November 2017.; also cf. Haddow (2012) for similar dental trait analysis

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y. (September 2022). "Ideas about "Race" in Nile Valley Histories: A Consideration of "Racial" Paradigms in Recent Presentations on Nile Valley Africa, from "Black Pharaohs" to Mummy Genomest". Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections.

- ^ Hanihara, Tsunehiko; Ishida, Hajime; Dodo, Yukio (July 2003). "Characterization of biological diversity through analysis of discrete cranial traits". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 121 (3): 241–251. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10233. PMID 12772212.

- ^ "When Mahalanobis D2 was used,the Naqadan and Badarian Predynastic samples exhibited more similarity to Nubian, Tigrean, and some more southern series than to some mid- to late Dynasticseries from northern Egypt (Mukherjee et al., 1955). The Badarian have been found to be very similar to a Kerma sample (Kushite Sudanese), using both the Penrose statistic (Nutter, 1958) and DFA of males alone (Keita,1990). Furthermore, Keita considered that Badarian males had a southern modal phenotype, and that together with a Naqada sample, they formed a southern Egyptian cluster as tropical variants together with a sample from Kerma". Zakrzewski, Sonia R. (April 2007). "Population continuity or population change: Formation of the ancient Egyptian state". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 132 (4): 501–509. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20569. PMID 17295300.

- ^ Godde, K. (2009). "An examination of Nubian and Egyptian biological distances: support for biological diffusion or in situ development?". Homo: Internationale Zeitschrift für die Vergleichende Forschung am Menschen. 60 (5): 389–404. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2009.08.003. ISSN 1618-1301. PMID 19766993.

- ^ Keita, Shomarka. "Analysis of Naqada Predynastic Crania: a brief report (1996)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-12-05. Retrieved 2022-02-22.

- ^ Keita, Shomarka; Boyce, A.J. (December 1996). "The Geographical Origins and Population Relationships of Early Ancient Egyptians", In Egypt in Africa, Theodore Celenko (ed). Indiana University Press. pp. 20–33. ISBN 978-0-253-33269-1.

- ^ Lovell Nancy and Prowse Tracy (17 December 2012). "Concordance of cranial and dental morphological traits and evidence f..." Archive.ph. Archived from the original on 17 December 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

Table 3 presents the MMD date for Badari, Qena, and Nubia in addition to Naqada and shows that these samples are all significantly different from each other. Since the two nonelite samples from Naqada are not significantly different, they were pooled for the cluster analysis that is presented in Figure 2 and which demonstrates that 1) the Naqada samples are more similar to each other than they are to the samples from the neighbouring Upper Egyptian or Lower Nubian sites and 2) the Naqada samples are more similar to the Lower Nubian protodynastic sample than they are to the geographically more proximate Egyptian samples.

- ^ Lovell Nancy and Prowse Tracy (17 December 2012). "Concordance of cranial and dental morphological traits and evidence f..." Archive.ph. Archived from the original on 17 December 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

the Naqada samples are more similar to each other than they are to the samples from the neighbouring Upper Egyptian or Lower Nubian sites

- ^ Lovell, Nancy C. (1999). "Egyptians, physical anthropology of". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Shubert, Steven Blake (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge. pp. 328–331. ISBN 0-415-18589-0.

- ^ Godde, Kanya (2018-07-01). "A new analysis interpreting Nilotic relationships and peopling of the Nile Valley". HOMO: Journal of Comparative Human Biology. 69 (4): 147–157. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2018.07.002. PMID 30055809.

- ^ Godde, K. (July 2018). "A new analysis interpreting Nilotic relationships and peopling of the Nile Valley". Homo: Internationale Zeitschrift für die Vergleichende Forschung am Menschen. 69 (4): 147–157. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2018.07.002. ISSN 1618-1301. PMID 30055809. S2CID 51865039.

- ^ Godde, Kane. "A biological perspective of the relationship between Egypt, Nubia, and the Near East during the Predynastic period (2020)". Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ a b Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 83–85, 97. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9.

- ^ Eltis, David; Bradley, Keith R.; Perry, Craig; Engerman, Stanley L.; Cartledge, Paul; Richardson, David (12 August 2021). The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 2, AD 500-AD 1420. Cambridge University Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-521-84067-5.

- ^ Candelora Danielle; Ben-Marzouk Nadia; Cooney Kathyln, eds. (31 August 2022). Ancient Egyptian society: challenging assumptions, exploring approaches. Abingdon, Oxon: Taylor & Francis. pp. 101–122. ISBN 978-0-367-43463-2.

- ^ Celenko, Theodore (1996). "The Geographical Origins and Population Relationships of Early Ancient Egyptians" In Egypt in Africa. Indianapolis, Ind.: Indianapolis Museum of Art. pp. 20–33. ISBN 0-936260-64-5.

- ^ Jr, William H. Stiebing; Helft, Susan N. (3 July 2023). Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. Taylor & Francis. pp. 209–212. ISBN 978-1-000-88066-3.

- ^ Sirak, K.A. (2021). "Social stratification without genetic differentiation at the site of Kulubnarti in Christian Period Nubia". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 7283. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.7283S. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-27356-8. PMC 8671435. PMID 34907168.

We find that the Kulubnarti Nubians were admixed with ~43% Nilotic related ancestry on average (individual proportions varied between ~36-54%) and the remaining ancestry reflecting a West Eurasian-related gene pool ultimately deriving from an ancestry pool like that found in the Bronze and Iron Age Levant. ... The Kulubnarti Nubians on average are shifted slightly toward present-day West Eurasians relative to present-day Nubians, who are estimated to have ~40% West Eurasian-related ancestry.

- ^ Hollfelder, Nina (2017). "Northeast African genomic variation shaped by the continuity of indigenous groups and Eurasian migrations". PLOS Genetics. 13 (8): e1006976. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006976. PMC 5587336. PMID 28837655.

All the populations that inhabit the Northeast of Sudan today, including the Nubian, Arab, and Beja groups showed admixture with Eurasian sources and the admixture fractions were very similar. ...Nubians are an admixed group with gene-flow from outside of Africa ... The strongest signal of admixture into Nubian populations came from Eurasian populations and was likely quite extensive: 39.41%-47.73%. ... Nubians can be seen as a group with substantial genetic material relating to Nilotes that later have received much gene-flow from Eurasians.

- ^ Haber, Marc (2017). "Chad Genetic Diversity Reveals an African History Marked by Multiple Holocene Eurasian Migrations". American Journal of Human Genetics. 99 (6): 1316–1324. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.10.012. PMC 5142112. PMID 27889059.

We found that most Ethiopians are a mixture of Africans and Eurasians. ... Eurasian ancestry in Ethiopians ranges from 11%–12% in the Gumuz to 53%–57% in the Amhara.

- ^ Ali, A. A. (2020). "Genome-wide analyses disclose the distinctive HLA architecture and the pharmacogenetic landscape of the Somali population". Scientific Reports. 10 (6): 1316–1324. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.5652A. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-62645-0. PMC 5142112. PMID 27889059.

Principal component analysis showed approximately 60% East African and 40% West Eurasian genes in the Somali population, with a close relation to the Cushitic and Semitic speaking Ethiopian populations.

![Predynastic human figures, Naqada.[5][6][7]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/48/Predynastic_human_figures.jpg/113px-Predynastic_human_figures.jpg)