Polish Americans (Polish: Polonia amerykańska) are Americans who either have total or partial Polish ancestry, or are citizens of the Republic of Poland. There are an estimated 8.81 million self-identified Polish Americans, representing about 2.67% of the U.S. population, according to the 2021 American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau.[3]

Polonia amerykańska | |

|---|---|

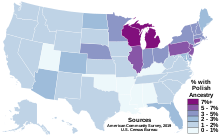

Americans with Polish ancestry by state according to the U.S. Census Bureau's American Community Survey in 2019 | |

| Total population | |

| Alone (one ancestry) 2,686,326 (2020 census)[1] 0.81% of the total US population Alone or in combination 8,599,601 (2020 census)[1] 2.59% of the total US population | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Northeast (New York · New Jersey · Maryland · Connecticut · Massachusetts · Pennsylvania (Luzerne County and Lackawanna County)) Midwest (Michigan · Illinois · Wisconsin · Ohio · Minnesota · Indiana · North Dakota · Nebraska · Iowa (Sioux City) · Some in Kansas · Missouri) · California · Growing in Arizona · Florida · Colorado | |

| Languages | |

| English (American English dialects) · Polish | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholicism · Protestantism · Judaism[2] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Poles • Polish Jews • Texan Silesians • Kashubian Americans • Czech Americans • Slovak Americans • Sorbian Americans |

The first eight Polish immigrants to British America came to the Jamestown colony in 1608, twelve years before the Pilgrims arrived in Massachusetts. Two Polish volunteers, Casimir Pulaski and Tadeusz Kościuszko, aided the Americans in the Revolutionary War. Casimir Pulaski created and led the Pulaski Legion of cavalry. Tadeusz Kosciuszko designed and oversaw the construction of state-of-the-art fortifications, including those at West Point, New York. Both are remembered as American heroes. Overall, around 2.2 million Poles and Polish subjects immigrated into the United States between 1820 and 1914, chiefly after national insurgencies and famine.[4] They included former Polish citizens of Roman Catholic, Protestant, Jewish or other minority descent.

Exact immigration figures are unknown owing to several complicating factors. Many immigrants were classified as "Russian", "German" or "Austrian" by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service as many former territories of Poland were under German, Austrian-Hungarian and Russian occupation between the 1790s and the 1910s. Complicating the U.S. Census figures further is the high proportion of Polish Americans who married people of other national descent. In 1940, about 50 percent married other American ethnics and a study in 1988 found that 54% of Polish Americans were of mixed ancestry from three generations or longer. The Polish American Cultural Center places a figure of Americans who have some Polish ancestry at 19–20 million.

In 2000, 667,414 Americans over five years old reported Polish as the language spoken at home, which is about 1.4% of the census groups who speak a language other than English or 0.25% of the U.S. population.

History

editPolish speakers in the United States

| |

Year

|

Speakers

|

| 1910a | 943,781

|

| 1920a | 1,077,392

|

| 1930a | 965,899

|

| 1940a | 801,680

|

| 1960a | 581,936

|

| 1970a | 419,912

|

| 1980[5] | 820,647

|

| 1990[6] | 723,483

|

| 2000[7] | 667,414

|

| 2011[8] | 607,531

|

| ^a Foreign-born white population only[9] | |

The history of Polish immigration to the United States can be divided into three stages, beginning with the first stage in the colonial era down to 1870, small numbers of Poles and Polish subjects came to America as individuals or in small family groups, and they quickly assimilated and did not form separate communities, with the exception of Panna Maria, Texas founded in the 1850s. For instance, Polish settlers came to the Virginia Colony as skilled craftsmen as early as 1608.[10][11] Some Jews from Poland even assimilated into cities which were Polish (and also other Slavic and sometimes additionally Jewish) bastions to conceal their Jewish identities.[12]

In the second stage from 1870 to 1914, Poles and Polish subjects formed a significant part of the wave of immigration from Germany, Imperial Russia, and Austria Hungary. The Poles, particularly Polish Jews, came in family groups, settled in and/or blended into largely Polish neighborhoods and other Slavic bastions, and aspired to earn wages that were higher than what they could earn back in Europe and so many took the ample job opportunities for unskilled manual labor in industry and mining. The main Ethnically-Polish-American organizations were founded because of high Polish interest in the Catholic church, parochial schools, and local community affairs. Relatively few were politically active.

During the third stage from 1914 to present, the United States has seen mass emigration from Poland, and the coming of age of several generations of fully assimilated Polish Americans. Immigration from Poland has continued into the early 2000s and began to decline after Poland had joined the European Union in 2004. The income levels have gone up from well below average, to above average. Poles became active members of the liberal New Deal Coalition from the 1930s to the 1960s, but since then, many have moved to the suburbs, and have become more conservative and vote less often Democratic.[13] Outside Republican and Democratic politics, politics such as those of Agudath Israel of America have heavily involved Polish-Jewish Americans.

Demographics

edit| Year | Number |

|---|---|

| 1900[14] | |

| 1970[15] | |

| 1980[16] | |

| 1990[17] | |

| 2000[18] | |

| 2010[19] | |

| 2020[3] |

Helena Lopata (1976) argues that Poles differed from most other ethnic groups in America in several ways. They did not plan to remain permanently and become "Americanized." Instead, they came temporarily to earn money, invest, and wait for the right opportunity to return. Their intention was to ensure a desirable social status in the old world for themselves. However, many of the temporary migrants decided to become permanent Americans.

Many found manual labor jobs in the coal mines of Pennsylvania and the heavy industries (steel mills, iron foundries, slaughterhouses, oil and sugar refineries), of the Great Lakes cities of Chicago, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Buffalo, Milwaukee, Cleveland, and Toledo.

The U.S. Census asked Polish immigrants to specify Polish as their native language beginning in Chicago in 1900, allowing the government to enumerate them as an individual nationality when there was no Polish nation-state.[20] No distinction is made in the American census between ethnically Polish Americans and descendants of non-ethnic Poles, such as Jews or Ukrainians, who were born in the territory of Poland and considered themselves Polish nationals. Therefore, some say, of the 10 million Polish Americans, only a certain portion are of Polish ethnic descent. On the other hand, many ethnic Poles when entering the US from 1795 to 1917, when Poland did not exist, did not identify themselves as ethnic Poles and instead identified themselves as either German, Austrian or Russian (this pertained to the nations occupying Poland from 1795 to 1917). Therefore, the actual number of Americans of at least partial Polish ancestry, could be well over 10 million. In the 2011 United States Census Bureau's Population Estimates, there are between 9,365,239 and 9,530,571 Americans of Polish descent, with over 500,000 being foreign-born.[21]

Historically, Polish-Americans have assimilated very quickly to American society. Between 1940 and 1960, only 20 percent of the children of Polish-American ethnic leaders spoke Polish regularly, compared to 50 percent for Ukrainians.[22] In the early 1960s, 3,000 of Detroit's 300,000 Polish-Americans changed their names each year. Language proficiency in Polish is rare in Polish-Americans, as 91.3% speak "English only."[21] In 1979, the 8 million respondents of Polish ancestry reported that only 41.5 percent had single ancestry, whereas 57.3% of Greeks, 52% of Italians and Sicilians, and 44% of Ukrainians had done so (clarification needed). Polish-Americans tended to marry exogamously in the postwar era in high numbers, and tended to marry within the Catholic population, often to persons of German (17%), Italian (10%), East European (8%), Irish (5%), French (4%), Spanish-speaking (2%), Lithuanian (2%), and English (1%) ancestry.[23]

Polish-born population

editPolish-born population in the U.S. since 2010:[24]

| Year | Number |

|---|---|

| 2010 | 475,503 |

| 2011 | 461,618 |

| 2012 | 440,312 |

| 2013 | 432,601 |

| 2014 | 424,460 |

| 2015 | 419,332 |

| 2016 | 424,928 |

| 2017 | 418,775 |

Communities

editThe vast majority of Polish immigrants settled in metropolitan areas, attracted by jobs in industry. The minority, by some estimates, only ten percent, settled in rural areas.

Historian John Bukowczyk noted that Polish immigrants in America were highly mobile, and 40 to 60 percent were likely to move from any given urban neighborhood within 10 years.[25] The reasons for this are very individualistic; Bukowczyk's theory is that many immigrants with agricultural backgrounds were eager to migrate because they were finally freed from the local plots of land they had owned in Poland. Others ventured into business and entrepreneurship, and the majority of them opened small retail shops such as bakeries, butcher shops, saloons, and print shops.[26]

Polish American Heritage Month is an event in October by Polish American communities, first celebrated in 1981.

Chicago

editOne of the most notable in size of the urban Polish American communities is in Chicago and its surrounding suburbs. Chicago is a city sprawling with Polish culture, billing itself as the largest Polish city outside of Poland, with approximately 185,000 Polish speakers,[27] making Polish the third most spoken language in Chicago. The influence of Chicago's Polish community is demonstrated by the numerous Polish-American organizations: the Polish Museum of America, Polish Roman Catholic Union of America (the oldest Polish American fraternal organization in the United States), Polish American Association, Polish American Congress, Polish National Alliance, Polish Falcons, Polish Highlanders Alliance of North America, and the Polish Genealogical Society of America. In addition, Illinois has more than one million people that are of Polish descent, the third largest ethnic group after the German and Irish Americans. The Chicago area has many Polish delis, restaurants, and churches.

Chicago's Polish community was concentrated along the city's Northwest and Southwest Sides, along Milwaukee and Archer Avenues, respectively. Chicago's Taste of Polonia festival is celebrated at the Copernicus Foundation, in Jefferson Park, every Labor Day weekend. Nearly 3 million people of Polish descent live in the area between Chicago and Detroit, including Northern Indiana, a part of the Chicago metropolitan area. The community has played a role as a staunch supporter of the Democratic machine, and has been rewarded with several congressional seats. The leading representative has been Congressman Dan Rostenkowski, one of the most powerful members of Congress (1959 to 1995), especially on issues of taxation, before he went to prison.[28]

New York metropolitan area

editThe New York metropolitan area, including Brooklyn in New York City, and North Jersey, is home to the second-largest community of Polish Americans[29] in the nation, and is now closely behind the Chicago metropolitan area's Polish population. Greenpoint, New York in Brooklyn is home to the Little Poland of New York City, while Williamsburg, Maspeth and Ridgewood also contain vibrant Polish communities. In 2014, the New York metropolitan area surpassed Chicago as the metropolitan area attracting the most new legal immigrants to the United States from Poland.[30][31][32]

Linden, Elizabeth, and Newark, New Jersey

editLinden, New Jersey in Union County, near Newark Liberty International Airport, has become heavily first-generation Polish in recent years.[when?] 15.6% of the residents five years old and above in the city of Linden primarily speak Polish at home and a variety of Polish-speaking establishments may be found by the Linden station, which is a direct line to Manhattan. St. Theresa's Roman Catholic Church offers masses in Polish.[citation needed]

In the early part of the 20th century, up to and immediately following the second World War, Newark, New Jersey and Elizabeth, New Jersey were the primary, historic centers of 'Polonia' as Polish-Americans of that era thought of themselves. Castle Garden and Ellis Island generation immigrants and those that followed them found employment in the industries of these two cities as well as Linden which housed oil refineries and auto manufacturing. Initial settlements were in Newark, primarily the "Ironbound" section, where St. Stanislaw Roman Catholic Church, followed by Casimir's Parish were the first parish churches founded and built by the communities there. In Elizabeth, the first parish serving the Polish community is St. Adalbert's Roman Catholic Church. All these parishes are over 100 years old, dating from the late 1800s, with churches constructed in the early 20th century. Post-war prosperity allowed many Polish Americans to disperse from the original core in New Jersey's industrial areas to the surrounding suburban communities. Documentation of their early history may be found on individual parish websites. Other significant centers of Polish settlement in New Jersey included Garfield, New Jersey, Manville in Somerset County, Trenton, New Jersey, and Camden, New Jersey.[citation needed]

Other areas

editIn Hudson County, New Jersey, Bayonne houses New Jersey's largest Polish American community, while Wallington in Bergen County contains the state's highest percentage of Polish Americans and one of the highest percentages in the United States, at over 40%. However, within New Jersey, Polish populations are additionally increasing rapidly in Clifton, Passaic County as well as in Garfield, Bergen County.

Riverhead, New York, located on eastern Long Island, contains a neighborhood known as Polish Town, where many Polish immigrants have continued to settle since the World War II era; the town has Polish architecture, stores, and St. Isidore's R.C. Church, and Polish Town hosts an annual summer Polish Fair. LOT Polish Airlines provides non-stop flight service between JFK International Airport in the Queens borough of New York City, Newark and Warsaw.[33]

The Kosciuszko Foundation is based in New York.

Wisconsin and Minnesota

editMilwaukee's Polish population has always been overshadowed by the city's more numerous German American inhabitants. Nevertheless, the city's once numerous Polish community built a number of Polish Cathedrals, among them the magnificent Basilica of St. Josaphat and St. Stanislaus Catholic Church. Many Polish residents and businesses are still located in the Lincoln Village neighborhood. The city is also home to Polish Fest, the largest Polish festival in the United States, where Polish Americans from all over Wisconsin and nearby Chicago, come to celebrate Polish Culture, through music, food and entertainment.[34] Polonia in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul is centered on Holy Cross Church in the Northeast Neighborhood of Minneapolis, where a vibrant Polish ministry continues to care for the Polish Roman Catholic Faithful.

Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Nebraska represent a different type of settlement with significant Polish communities having been established in rural areas. Historian John Radzilowski estimates that up to a third of Poles in Minnesota settled in rural areas, where they established 40 communities, that were often centered around a Catholic church.[35] Most of these settlers came from the Polish lands that had been taken by Prussia during the Partitions, with a sub-group coming from Silesia. The Kaszub minority, from Poland's Baltic coast, was also strongly represented among Polish immigrants to Minnesota, most notably in Winona. Despite relative isolation from Poland and larger urban Polonian communities, due to strong community integration these communities continued speaking Polish into the 1970s in some cases and continue to have a strong Polish identity.

Michigan

editMichigan's Polish population of more than 850,000 is the third-largest among U.S. states, behind that of New York and Illinois. Polish Americans make up 8.6% of Michigan's total population. The city of Detroit has a very large Polish community, which historically settled in Poletown and Hamtramck on the east side of Detroit, the neighborhoods along Michigan Avenue from 23rd street into east Dearborn, the west side of Delray, parts of Warrendale and several sections of Wyandotte downriver. The northern part of Poletown was cleared of residents, to make way for the General Motors Detroit/Hamtramck Assembly plant. Today it contains some of the most opulent Polish churches in America like St. Stanislaus, Sweetest Heart of Mary, St. Albertus, St. Josephat and St. Hyacinthe. Michigan as a state has Polish populations throughout. In addition to metropolitan Detroit, Grand Rapids, Bay City, Alpena and the surrounding area, the thumb of Michigan, Manistee, and numerous places in northern lower Michigan and south-central Michigan also have sizable Polish populations.

The Polish influence is still felt throughout the entire metropolitan Detroit area, especially the suburb of Wyandotte, which is slowly emerging as the major center of Polish American activities in the state. An increase in new immigration from Poland is helping to bolster the parish community of Our Lady of Mount Carmel and a host of Polish American civic organizations, located within the city of Wyandotte. Also, the Detroit suburb of Troy is home to the American Polish Cultural Center, where the National Polish-American Sports Hall of Fame has over 200 artifacts on display from over 100 inductees, including Stan Musial and Mike Krzyzewski.[36] St. Mary's Preparatory, a high school in Orchard Lake with historically Polish roots, sponsors a popular annual Polish County Fair that bills itself as "America's Largest High School Fair."

Outside of Metro Detroit, Polish Americans retain a strong presence in Northern Michigan. The town of Cedar in Leelanau County retains a large Polish presence, and is home to a Polish Art Center, as well as an annual polka festival.[37] The counties of Alpena, Presque Isle, and Huron also have a large percentage and population of families of Polish immigrants.

Ohio

editOhio is home to more than 440,000 people of Polish descent, their presence felt most strongly in the Greater Cleveland area, where half of Ohio's Polish population resides.[38] The city of Cleveland, Ohio has a large Polish community, especially in historic Slavic Village, as part of its Warszawa Section. Poles from this part of Cleveland migrated to the suburbs, such as Garfield Heights, Parma and Seven Hills. Parma has even recently been designated a Polish Village commercial district.[39] Farther out, other members of Cleveland's Polish community live in Brecksville, Independence and Broadview Heights. Many of these Poles return to their Polish roots by attending masses at St. Stanislaus Church, on East 65th Street and Baxter Avenue.

Cleveland's other Polish section is in Tremont, located on Cleveland's west side. The home parishes are St. John Cantius and St. John Kanty.

Other Polish language churches in Cleveland city include St. Casimir, St. Barbara, and Immaculate Heart of Mary. Outside of annual church festivals, other major city celebrations include Dyngus Day and the Slavic Village Harvest Festival, celebrating with Polish food, customer, and Polka music.[40] Cleveland is home to the Polka Hall of Fame.

Poles in Cleveland were instrumental in forming the Third Federal Savings and Loan in 1938. After seeing fellow Poles discriminated against by Cleveland's banks, Ben Stefanski formed Third Federal. Today the Stefanski family still controls the bank. Unlike Cleveland's KeyBank and National City Corp., which have their headquarters in Downtown Cleveland, Third Federal is on Broadway Avenue in the Slavic Village neighborhood. Third Federal Savings and Loan is in the top 25 saving and loan institutions in the United States. In 2003, they acquired a Florida banking company and have branches in Florida and Ohio.

Texas

editPanna Maria, Texas, was founded by Upper Silesian settlers on Christmas Eve in 1854. Some people still speak Texas Silesian. Silesian is regarded as either a dialect of Polish, or a distinct language. Cestohowa, Kosciusko, Falls City, Polonia, New Waverly, Brenham, Marlin, Bremond, Anderson, Bryan, and Chappell Hill were either founded or populated by the Poles.[citation needed]

Others

editOther industrial cities with major Polish communities include Buffalo, New York; Boston; Baltimore; New Britain, Connecticut; Dallas, Houston, Portland, Oregon; Minneapolis; Philadelphia; Columbus, Ohio; Erie, Pennsylvania; Rochester, New York; Syracuse, New York; Los Angeles; San Francisco; Seattle; Pittsburgh; South Bend, Indiana; central/western Massachusetts; and Duluth, Minnesota. There is a relatively large Polish population in Kansas City and Saint Louis, Missouri in addition to the area's many German-Americans.

Luzerne County, in northeastern Pennsylvania, is the only county in the United States where a plurality of residents state their ancestry as Polish. (See: Maps of American ancestries) This includes the cities of Wilkes-Barre, Pittston, Hazleton, and Nanticoke. Many of the immigrants were drawn to this area, because of the mining of Anthracite coal in the region. Polish influences are still common today, in the form of church bazaars, polka music, and Polish cuisine. It is widely believed that Boothwyn, Pennsylvania, has one of the fastest growing Polish communities in the United States.

In 2007, at the urging of Attorney Adrian Baron and the local Polonia Business Association, New Britain, Connecticut officially designated its Broad Street neighborhood as Little Poland, where an estimated 30,000 residents claim Polish heritage. Visitors can do an entire day's business completely in Polish including banking, shopping, dining, legal consultations, and even dance lessons. The area has retained its Polish character since 1890. There is also a Polish community in Las Vegas.[41]

By state totals

editAs of the 2021 American Community Survey, the distribution of Polish Americans across the 50 states and DC is as presented in the following table:

| State | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 28,557 | 0.57% |

| Alaska | 13,693 | 1.86% |

| Arizona | 153,023 | 2.16% |

| Arkansas | 22,785 | 0.76% |

| California | 452,019 | 1.15% |

| Colorado | 133,378 | 2.33% |

| Connecticut | 240,390 | 6.67% |

| Delaware | 39,254 | 4.00% |

| District of Columbia | 15,330 | 2.24% |

| Florida | 478,483 | 2.24% |

| Georgia | 108,837 | 1.02% |

| Hawaii | 12,894 | 0.89% |

| Idaho | 21,739 | 1.20% |

| Illinois | 825,037 | 6.43% |

| Indiana | 197,807 | 2.93% |

| Iowa | 38,951 | 1.23% |

| Kansas | 37,188 | 1.27% |

| Kentucky | 40,899 | 0.91% |

| Louisiana | 20,842 | 0.45% |

| Maine | 30,038 | 2.21% |

| Maryland | 172,300 | 2.80% |

| Massachusetts | 283,050 | 4.05% |

| Michigan | 784,200 | 7.79% |

| Minnesota | 236,895 | 4.18% |

| Mississippi | 11,882 | 0.40% |

| Missouri | 97,813 | 1.59% |

| Montana | 18,912 | 1.75% |

| Nebraska | 61,910 | 3.17% |

| Nevada | 52,563 | 1.72% |

| New Hampshire | 53,939 | 3.93% |

| New Jersey | 470,082 | 5.09% |

| New Mexico | 20,065 | 0.95% |

| New York | 866,242 | 4.31% |

| North Carolina | 148,987 | 1.44% |

| North Dakota | 16,032 | 2.07% |

| Ohio | 414,587 | 3.52% |

| Oklahoma | 29,735 | 0.75% |

| Oregon | 68,963 | 1.64% |

| Pennsylvania | 757,627 | 5.84% |

| Rhode Island | 36,411 | 3.33% |

| South Carolina | 74,893 | 1.47% |

| South Dakota | 13,600 | 1.54% |

| Tennessee | 74,289 | 1.08% |

| Texas | 287,928 | 1.00% |

| Utah | 25,477 | 0.79% |

| Vermont | 23,234 | 3.62% |

| Virginia | 151,996 | 1.77% |

| Washington | 126,400 | 1.66% |

| West Virginia | 28,241 | 1.57% |

| Wisconsin | 481,126 | 8.19% |

| Wyoming | 9,752 | 1.69% |

| United States | 8,810,275 | 2.67% |

Religion

editAs in Poland, the majority of Polish immigrants are Roman Catholic. Historically, less than 5% of Americans who identified as Polish would state any other religion but Roman Catholic. Jewish immigrants from Poland, largely without exception, self identified[43] as "Jewish," "German Jewish," "Russian Jewish," or "Austrian Jewish" when inside the United States, and faced a historical trajectory far different from that of the Polish Catholics.[44]

Polish Americans built dozens of Polish Cathedrals in the Great Lakes and New England regions and in the Mid-Atlantic States. Chicago's Poles founded the following churches: St. Stanislaus Kostka, Holy Trinity, St. John Cantius, Holy Innocents, St. Helen, St. Fidelis, St. Mary of the Angels, St. Hedwig, St. Josaphat, St. Francis of Assisi (Humboldt Park), St. Hyacinth Basilica, St. Wenceslaus, Immaculate Heart of Mary, St. Stanislaus B&M, St. James (Cragin), St. Ladislaus, St. Constance, St. Mary of Perpetual Help, St. Barbara, SS. Peter & Paul, St. Joseph (Back of the Yards), Five Holy Martyrs, St. Pancratius, St. Bruno, St. Camillus, St. Michael (South Chicago), Immaculate Conception (South Chicago), St. Mary Magdalene, St. Bronislava, St. Thecla, St. Florian, St. Mary of Częstochowa (Cicero), St. Simeon (Bellwood), St. Blase (Summit), St. Glowienke (Downers Grove), St. John the Fisherman (Lisle), St. Isidore the Farmer (Blue Island), St. Andrew the Apostle (Calumet City) and St. John the Baptist (Harvey), as well as St. Mary of Nazareth Hospital, on the Near West Side.

Poles established approximately 50 Roman Catholic parishes in Minnesota. Among them: St. Wojciech (Adalbert) and St. Kazimierz (Casimir) in St. Paul; Holy Cross, St. Philip, St. Hedwig (Jadwiga Slaska) and All Saints, in Minneapolis; Our Lady Star of the Sea, St. Casimir's, and SS. Peter and Paul in Duluth; and St. Kazimierz (Casimir) and St. Stanislaw Kostka in Winona. A few of the parishes of particular note, founded by Poles elsewhere in Minnesota, include: St. John Cantius in Wilno; St. Jozef (Joseph) in Browerville; St. John the Baptist in Virginia; St. Mary in Częstochowa; St. Wojciech (Adalbert) in Silver Lake; Our Lady of Mount Carmel in Opole; Our Lady of Lourdes in Little Falls; St. Stanislaus B&M in Sobieski; St. Stanislaus Kostka in Bowlus; St. Hedwig in Holdingford; Sacred Heart in Flensburg; Holy Cross in North Prairie; Holy Cross in Harding; and St. Isadore in Moran Township.

Poles in Cleveland established St. Hyacinth's (now closed), Saint Stanislaus Church (1873), Sacred Heart (1888–2010) Immaculate Heart of Mary (1894), St. John Cantius (Westside Poles), St. Barbara (closed), Sts Peter and Paul Church (1927) in Garfield Heights, Saint Therese (1927) Garfield Heights, Marymount Hospital (1948) Garfield Heights, and Saint Monica Church (1952) Garfield Heights. Also, the Polish Community created the Our Lady of Częstochowa Shrine on the campus of Marymount Hospital.[45]

Poles in South Bend, Indiana, founded four parishes: St. Hedwig Parish (1877), St. Casimir Parish (1898), St. Stanislaus Parish (1907), and St. Adalbert Parish, South Bend (1910).

Circa 1897, in Pittsburgh's Polish Hill, Immaculate Heart of Mary, modeled on St. Peter's Basilica in Rome was founded.[46]

Polish Americans preserved their longstanding tradition of venerating the Lady of Czestochowa in the United States. Replicas of the painting are common in Polish American churches and parishes, and many churches and parishes are named in her honor. The veneration of the Virgin Mary in Polish parishes is a significant difference between Polish Catholicism and American Catholicism; Polish nuns in the Felician Order for instance, took to Marianism as the cornerstone of their spiritual development, and Polish churches in the U.S. were seen as "cult-like" in their veneration of Mary.[47] Religious catechism and writings from convents found that Polish nuns in the Felician Sisters and The Sisters of the Holy Family of Nazareth were taught to have "a sound appreciation of Mary's role in the mystery of the Redemption” and “a filial confidence in her patronage," more explicitly, “to be . . . a true daughter to the immaculate Virgin Mary." The Marianism that was taught in Polish parish schools in the United States was done independent of the Catholic Church, and demonstrated autonomy on the part of the nuns who taught Polish American youths. It is notable that there was a concurrent movement in Poland that eventually led to a separatist Catholic church, the Mariavite Church, which greatly expanded the veneration of the Virgin Mary in its doctrine. In Poland, the Virgin Mary was believed to serve as a mother of mercy and salvation for Catholics, and throughout the Middle Ages, Polish knights prayed to her before battle. Polish American churches featured replicas of the Lady of Częstochowa, which was on feature at the Jasna Góra Monastery and holds national and religious significance because of its connection to a victorious military defense in 1655. Several towns in America are named Częstochowa, in commemoration of the town in Poland.[47]

Though the majority of Polish Americans remained loyal to the Catholic Church, a breakaway Catholic church was founded in 1897 in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Polish parishioners founded the church to assert independence from the Catholic Church in America. The split was in rebellion from the church leadership, then dominated by Irish bishops and priests, and lacking Polish speakers and Polish church leaders. It exists today with 25,000 parishioners and remains independent from the authority of the Roman Catholic Church.

Poland is also home to followers of Protestantism and the Eastern Orthodox Church. Small groups of both of these groups also immigrated to the United States. One of the most celebrated painters of religious icons in North America today is a Polish American Eastern Orthodox priest, Fr. Theodore Jurewicz, who singlehandedly painted New Gračanica Monastery in Third Lake, Illinois, over the span of three years.[48]

A small group of Lipka Tatars, originating from the Białystok region, helped co-found the first Muslim organization in Brooklyn, New York, in 1907, and later, a mosque, which is still in use.[49]

Social status

editIn 1969, the median family income was $8,849 for Polish Americans. The median family income for all families in the United States in 1968 was $7,900. Leonard F. Chrobot summarizes the Census data for 1969:[50]

The typical Polish American male was born in the United States, spoke Polish in his home when he was a child, but speaks English now, is 38.7 years old (female: 40.9), and is married to a Polish wife. If he is between 25 and 34 years of age, he completed 12.7 years of school, and if he is over 35, he completed 10.9 years. His median family income is $8,849. The male works as a craftsman, foreman, or kindred occupation, and his wife is employed as a clerical worker.

In 2017, by educational attainment, the U.S. Census estimates that 42.5% have bachelor's degrees or higher, whereas the American population as a whole is 32.0%. However, among other Slavic-American groups, most notably Russian (60.4%) and Ukrainian (52.2%), Americans of Polish descent fall short in educational attainment.[51] The median household income for Americans of Polish descent is estimated by the U.S. Census as $73,452, with no statistically significant differences from other Slavic-American groups, Czech, Slovak, and Ukrainian. The median household income for those of Russian ancestry has been reported as higher on the U.S. Census, at $80,554.[21]

| Ethnicity | Household Income | College degrees (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Russian | $80,554 | 60.4 |

| Polish | $73,452 | 42.5 |

| Czech | $71,663 | 45.4 |

| Serbian | $79,135 | 46.0 |

| Slovak | $73,093 | 44.8 |

| Ukrainian | $75,674 | 52.2 |

| White non-Hispanic | $65,845 | 35.8 |

| Total U.S. Population | $60,336 | 32.0 |

Politics

editPolish-Americans comprise a large voting bloc sought after by both the Democratic and Republican parties. Polish Americans comprise 3.2% of the United States population but are concentrated in several Midwestern swing states that make issues important to Polish-Americans more likely to be heard by presidential candidates. According to John Kromkowski, Polish-Americans make up an "almost archetypical swing vote".[52] The Piast Institute found that Polish Americans are 36% Democrats, 33% Independents, and 26% are Republicans as of 2008. Ideologically, they were categorized as being in the more conservative wing of the Democratic Party, and demonstrated a much stronger inclination for third-party candidates in presidential elections than the American public.[53]

Historically, Polish-American voters have swung from the Democratic and Republican parties depending on economic and social politics. In the 1918 election, Woodrow Wilson courted Poles through his promises of Polish autonomy. They gave strong support to the wet Catholic Al Smith in 1928. They gave even more enthusiastic support to the New Deal Coalition and President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In World War II they were fiercely against Nazi Germany. FDR consistently won over 90% of the Polish vote during his four terms.

Polish-Americans founded the Polish American Congress (PAC) in 1944 to create strong leadership and represent Polish interests during World War II. FDR met with the PAC and assured Poles of a peaceful and independent Poland following the war. When this did not come to fruition, and with the publication of Arthur Bliss Lane's I Saw Poland Betrayed in 1947, Polish-Americans came to feel that they had been betrayed by the United States government.[54] John F. Kennedy won a majority of the Polish vote in 1960, owing in part to his Catholicism and connection to ethnic communities and the labor movement. Since then, Polish voters have been tied to the more conservative wing of the Democratic Party, but shifted away from the Democrats over social issues such as abortion. Poland's liberation from Soviet occupation during the 1980s was championed to Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush, but Bill Clinton seized Polish voters through his expansion of NATO. The relevance of the Polish-American vote has been in question in recent elections, as Americans of Polish descent have assimilated to U.S. society and increased their rate of exogamous marriages.[citation needed]

In modern politics, the Polish-American vote continues to have influence in the United States. The American Polish Advisory Council, a politically involved network of Polish organizations, has created a political platform and convention, and has shared its agenda with politicians, both at the state and federal level.

Anti-Polonism

editThe Polish community was long the subject of anti-Polish sentiment in America. The word Polack has become an ethnic slur. This prejudice was partially associated with anti-Catholicism, and early 20th century worries about being overrun by immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe.

Culture

editThe cultural contributions of Polish Americans span a broad spectrum, including in media, in the publishing industry, in religion, art, food, museums, and festivals.

Media

editAmong the most notable Polish American media groups are Hippocrene Books (founded by Polish American George Blagowidow); TVP Polonia; Polsat 2 International; TVN International; Polvision; TV4U New York; WEUR Radio Chicago; Polish Radio External Service (formerly Radio Polonia); Polonia Today and the Warsaw Voice. There are also Polish American newspapers and magazines, such as the Dziennik Związkowy, PL magazine,[55] Polish Weekly Chicago, the Super Express USA and Nowy Dziennik in New York and Tygodnik Polski and The Polish Times in Detroit, not to mention the Ohio University Press Series in Polish American Studies,[56] Przeglad Polski Online, Polish American Journal,[57] the Polish News Online,[58]Am-Pol Eagle Newspaper,[59] and Progress for Poland,[60] among others.

Cultural identity

editEven in long-integrated communities, remnants of Polish culture and vocabulary remain. Roman Catholic churches built by Polish American communities often serve as a vehicle for cultural retention.

During the 1950s–1970s, the Polish wedding was often an all-day event. Traditional Polish weddings in Chicago metropolitan area, in areas such as the southeast side of Chicago, inner suburbs like Calumet City and Hegewisch, and Northwest Indiana suburbs, such as Whiting, Hammond and East Chicago, always occurred on Saturdays. The receptions were typically held in a large hall, such as a VFW Hall. A polka band of drums, a singer, accordion, and trumpet, entertained the people, as they danced traditional dances, such as the oberek, "Polish Hop" and the waltz. The musicians, as well as the guests, were expected to enjoy ample amounts of both food and drink. Foods, such as Polish sausage, sauerkraut, pierogi and kluski were common. Common drinks were beer, screwdrivers and highballs. Many popular Polish foods became a fixture in the American cuisine of today, including kiełbasa (Polish sausage), babka cake, kaszanka, pierogi, and, especially around the time of Ash Wednesday and the beginning of Lent, pączki doughnuts.

Polish American cultural groups include Polish American Arts Association and the Polish Falcons.

Among the many Polish American writers are a number of poets, such as Hedwig Gorski, John Guzlowski, Cecilia Woloch, and Mark Pawlak (poet and editor), along with novelists Leslie Pietrzyk, Suzanne Strempek Shea[61] and others.

Museums

editAmong the best known Polish American museums are the Polish Museum of America in Chicago's old Polish Downtown; founded in 1935, the largest ethnic museum in the U.S. sponsored by the Polish Roman Catholic Union of America. The Museum Library ranks as one of the best outside of Poland. Equally ambitious is the Polish American Museum located in Port Washington, New York, founded in 1977. It features displays of folk art, costumes, historical artifacts and paintings, as well as bilingual research library with particular focus on achievements of the people of Polish heritage in America.[62][63] There is also the Polish Cultural Institute and Museum of Winona, Minnesota, known informally as "The Polish Museum of Winona." Formally established in 1979 by Father Paul Breza, the Polish Museum of Winona features exhibits pertaining to Winona's Kashubian Polish culture and hosts a wide range of events celebrating America's Polish-American heritage in general.

Festivals

editThere are a number of unique festivals, street parties and parades held by the Polish American community. Polish Fest in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, which is a popular annual festival, takes place at Henry Maier Festival Park. It is also the largest Polish festival in the United States. It attracts Polish Americans from all over Wisconsin and nearby Chicago, who come to celebrate Polish culture through music, food and entertainment. New York City is home to the New York Polish Film Festival, an annual film festival showcasing current and past films of Polish cinema. NYPFF is the only annual presentation of Polish films in New York City and the largest festival promoting and presenting Polish films on the East Coast.[64]

The Polish Festival in Syracuse's Clinton Square has become the largest cultural event in the history of the Polish community in Central New York. There's also the Taste of Polonia festival held in Chicago every Labor Day weekend since 1979 at the Copernicus Cultural and Civic Center in the Jefferson Park area. The Polish Festival in Portland, Oregon is reported to be the largest in the Western United States.[65] One of the newest and most ambitious festivals is the Seattle Polish Film Festival organized in conjunction with the Polish Film Festival in Gdynia, Poland. Kansas City, Kansas is home to a large Polish population and for the last 31 years, All Saints Parish has hosted Polski Day [2]. And last, but not least, there's the Pierogi Fest in Whiting, Indiana with many more attractions other than Polish pierogi, and the Wisconsin Dells Polish Fest.[61]

Holidays

edit- Kosciuszko Day February 4

- Casimir Pulaski Day March (Illinois regional)

- Feast of the Annunciation March 25

- Pączki Day (Fat Tuesday)

- Constitution Day May 3

- Dyngus Day (Easter Monday)

- Feast of Our Lady of Czestochowa August 26

- Dozhinki September

- General Pulaski Memorial Day October 11

- Feast of the Immaculate Conception December 8

- Wigilia December 24

Polish Americans carried on celebrations of Constitution Day throughout their time in the United States without political suppression. In Poland, from 1940 to 1989, the holiday was banned by Nazi and Soviet occupiers.[66]

Contributions to American culture

editPolish-Americans have influenced American culture in various ways. Most prominent among these is that Jefferson drafting the Constitution of the United States was inspired by religious tolerance of the Warsaw Confederation,[67] which guaranteed freedom of conscience.

The Polish culture left also culinary marks in the United States – the inclusion of traditional Polish cuisine such as pierogi, kiełbasa, gołąbki. Some of these Polish foods were tweaked and reinvented in the new American environment, such as Chicago's Maxwell Street Polish Sausage.

Polish Americans have also contributed to altering the physical landscape of the cities they have inhabited, erecting monuments to Polish-American heroes such as Kościuszko and Pulaski. Distinctive cultural phenomena such as Polish flats or the Polish Cathedral style of architecture became part and parcel of the areas where Polish settlement occurred.

Poles' cultural ties to Roman Catholicism have also influenced the adoption of such distinctive rites like the blessing of the baskets before Easter in many areas of the United States by fellow Roman Catholics.

Architectural influence

editEarly Polish immigrants built houses with high-pitched roofs in the United States. The high-pitched roof is necessary in a country subject to snow, and is a common feature in Northern and Eastern European architecture. In Panna Maria, Texas, Poles built brick houses with thick walls and high-pitched roofs. Meteorological and soil data show that region in Texas is subject to less than 1 inch of snow[68] and a meteorological study conducted 1960-1990 found the lowest one-day temperature ever recorded was 5 degrees Fahrenheit on January 21, 1986, highly unlikely to support much snow.[69] The shaded veranda that was created by these roofs was a popular living space for the Polish Texans, who spent much of their time there to escape the hot temperatures of subtropical Texas. The Poles in Texas added porches to these verandas, often in the southward windy side, which is an alteration to traditional folk architecture.[70] According to oral histories recorded from descendants, the verandas were used for "almost all daily activities from preparing meals to dressing animal hides."[70] The Poles in Texas put straw thatching on their roofs until the early 1900s, another European influence. The first house built by a Pole in Panna Maria is the John Gawlik House, constructed in 1858. The building still stands and is visited as a historical attraction in the cultural history of Texas. In 2011, the San Antonio Conservation Society financed a replacement of the building's roof, identifying it as a "historically and architecturally significant building."[71]

Military

editOrganizations like the Polish Legion of American Veterans were organized to memorialize the Polish contribution to the American military.[72] Those who contributed to the Polish military created Polish Army Veterans' Association in America.[73]

See also

edit- European Americans

- Kashubian Americans

- Kashubian Diaspora

- Polish American Football League

- Polish Australians

- Polish Brazilians

- Polish British

- Polish Canadians

- Polish Cathedral style

- Polish-American organized crime

- Polish-American vote

Lists

editCitations

edit- ^ a b "Races and Ethnicities USA 2020". United States census. September 21, 2023. Retrieved October 21, 2023.

- ^ One Nation Under God: Religion in Contemporary American Society, p. 120

- ^ a b c "Table B04006 - People Reporting Ancestry - 2021 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 12, 2022. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ^ Polonia amerykańska, p. 40

- ^ "Appendix Table 2. Languages Spoken at Home: 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2007". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ "Detailed Language Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for Persons 5 Years and Over --50 Languages with Greatest Number of Speakers: United States 1990". United States Census Bureau. 1990. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- ^ "Language Spoken at Home: 2000". United States Bureau of the Census. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ "Detailed Languages Spoken at Home by English-Speaking Ability for the Population 5 Years and Over: 2011" (PDF). census.gov. US Census Bureau. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 September 2019.

- ^ "Mother Tongue of the Foreign-Born Population: 1910 to 1940, 1960, and 1970". United States Census Bureau. March 9, 1999. Archived from the original on September 8, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Waldo, Arthur Leonard (1977). True Heroes of Jamestown. American Institute of Polish Culture. ISBN 978-1-881284-11-6.

- ^ Obst, Peter J. (2012-07-20). "Jamestown 1608 Marker". Poles in America Foundation. Retrieved 2019-08-03.

- ^ See the reference to Anusim. Additionally, refer to the similar case of John Kerry's paternal grandfather, a non-Polish subject who immigrated to Boston and passed for a Czech-Austrian Hungarian Catholic.

- ^ Greene, Victor (1980). "Poles". In Thernstrom, Stephan; Orlov, Ann; Handlin, Oscar (eds.). Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups. Harvard University Press. pp. 787–803. ISBN 0674375122. OCLC 1038430174.

- ^ "Waclaw Kruszka, Historya Polska w Ameryce, Milwaukee 1905, p. 65 (in Polish)" (PDF). The Polish-American Liturgical Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ Polish Americans, Status in an ethnic Community. by Helena Lopata, p. 89

- ^ "Rank of States for Selected Ancestry Groups with 100,00 or more persons: 1980" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population Detailed Ancestry Groups for States" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 18 September 1992. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ "Ancestry: 2000". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ "Total ancestry categories tallied for people with one or more ancestry categories reported 2010 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ "About the Population Census". Flps.newberry.org. Archived from the original on 11 December 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ Bukowczyck, p. 108

- ^ Bukowczyck, p. 109

- ^ "American FactFinder - Results". Archived from the original on 2020-02-14. Retrieved 2018-04-23.

- ^ Bukowczyk, pg. 35.

- ^ Bukowczyk, pg. 36.

- ^ The Polish Community in Metro Chicago:A Community Profile of Strengths and Needs, A Census 2000 Report, published by the Polish American Association June 2004, p. 18

- ^ Tomasz Inglot, and John P. Pelissero. "Ethnic Political Power in a Machine City Chicago's Poles at Rainbow's End." Urban Affairs Review (1993) 28#4 pp: 526-543.

- ^ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2011 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 2012-11-02.

- ^ "Supplemental Table 2. Persons Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident Status by Leading Core Based Statistical Areas (CBSAs) of Residence and Region and Country of Birth: Fiscal Year 2014". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ^ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2013 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ^ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2012 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ^ "POLISH AIRLINES LOT". LOT POLISH AIRLINES. Retrieved 2012-11-17.

- ^ Gauper, Beth (2007-05-27). "Polish for a day". MidwestWeekends.com. St. Paul Pioneer Press. Archived from the original on 2008-08-28. Retrieved 2008-01-11.

- ^ John Radzilowski. Poles in Minnesota. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2005. p. 6

- ^ "National Polish-American Sports Hall of Fame Artifacts on Display at the American Polish Cultural Center". National Polish-American Sports Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2009-02-23. [dead link]

- ^ "Polish Art Center - Contact Us". www.polartcenter.com. Retrieved 2022-03-01.

- ^ Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "American FactFinder - Results". Factfinder2.census.gov. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ "Polish Village In Parma Ohio". Facebook.com. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "The Cleveland Society of Poles | Polish Foundation | Cleveland Ohio". Clevelandsociety.com. Retrieved 2012-09-10.

- ^ Simich, Jerry L.; Wright, Thomas C. (7 March 2005). The Peoples Of Las Vegas: One City, Many Faces. University of Nevada Press. ISBN 9780874176513.

- ^ "Table B04006 - People Reporting Ancestry - 2021 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, All States". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 6, 2023. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ^ See "Jewish Surnames (Supposedly) Explained" in regards to name changes, self-identification, &c. as pertaining to Jewish and other immigrants at Ellis Island.

- ^ Radzilowski, John (2009). "A Social History of Polish-American Catholicism". U.S. Catholic Historian. 27 (3): 21–43. doi:10.1353/cht.0.0018. S2CID 161664866. Project MUSE 364512.

- ^ "Our Lady of Czestochowa Shrine". Marymount Hospital. Archived from the original on 6 October 2010. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ "A History of Polish Hill and the PHCA". Retrieved 2006-12-22.

- ^ a b Mary the Messiah: Polish Immigrant Heresy and the Malleable Ideology of the Roman Catholic Church, 1880-1930. John J. Bukowczyk. Journal of American Ethnic History. Vol. 4, No. 2 (Spring, 1985), pp. 5-32

- ^ "Serbian Monastery of New Gracanica – History". Newgracanica.com. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Religion: Ramadan". Time. 1937-11-15. Archived from the original on November 2, 2007. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ Leonard F. Chrobot, "The Elusive Polish American." Polish American Studies 30#1 (1973), pp. 54-59 at p. 58 online.

- ^ Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "U.S. Census website". Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Romney hopes Polish visit can pay dividends in swing states – Political Hotsheet". CBS News. 2012-08-01. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ "No Polish jokes on Romney's tour". Phillytrib.com. 2012-08-05. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ^ Ubriaco, Robert. Jr. "Giving Credit where credit is due: Cold War political culture, Polish American politics, the Truman Doctrine, and the Victory Thesis." The Polish Review. Vol LI. No. 3-4. 2006; 263-281.

- ^ "PL - polsko-amerykański dwujęzyczny miesięcznik / Polish-American bilingual monthly". Plmagazine.net. Archived from the original on 2012-10-13. Retrieved 2012-09-10.

- ^ "Ohio University Press & Swallow Press". Ohioswallow.com. Retrieved 2012-09-10.

- ^ "Welcome to the Polish American Journal". Polamjournal.com. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Polsko Amerykański portal - Polish American portal". Polishnews.Com. Retrieved 2012-09-10.

- ^ "The Am-Pol Eagle". Ampoleagle.com. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Progress for Poland - Chicago: Fakty, Wiadomości, Opinie..." Progress for Poland. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ a b "Polish American Historical Association - Resources and Supported Links". Polishamericanstudies.org. Archived from the original on 2017-11-25. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ Smithsonian Magazine, Polish American Museum Archived 2008-09-26 at the Wayback Machine at Smithsonian.com

- ^ James Barron, the New York Times, If you're thinking of living in:; Port Washington Published: August 8, 1982

- ^ "Święto polskiego kina w Nowym Jorku" (in Polish). Wirtualna Polska. 6 May 2009. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ "Polish Festival - Press Release". Archived from the original on 2011-12-30. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- ^ "May 3rd Polish Constitution Day". Ampoleagle.com. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Sandra Lapointe. The Golden Age of Polish Philosophy: Kazimierz Twardowski's Philosophical Legacy. Springer. 2009. pp. 2-3. [1]

- ^ "Intellicast - Panna Maria Historic Weather Averages in Texas (78144)". Intellicast.com. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-21. Retrieved 2013-04-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Francis Edward Abernathy (1 August 2000). Publications of the Texas Folklore Society. University of North Texas Press. pp. 132–. ISBN 978-1-57441-092-1. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ^ "mySouTex.com - Grant will replace roof of 1858 Panna Maria house". Mysoutex.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ "PLAV History". Plav.org. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ LACHOWICZ, TEOFIL; Juszczak, Albert (2010). "The Polish Army Veterans Association of America (A Historical Outline)". The Polish Review. 55 (4): 437–439. doi:10.2307/27920674. ISSN 0032-2970. JSTOR 27920674. S2CID 254449436.

Sources and further reading

edit- Bukowczyk, John J. A history of the Polish Americans (2nd ed. Routledge, 2017) online

- first edition published as Bukowczyk, John J. (1986). And My Children Did Not Know Me: A History of the Polish-Americans. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-30701-5. OCLC 59790559.

- Bukowczyk, John J. (1996). Polish Americans and Their History: Community, Culture, and Politics. Pittsburgh, Pa: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 0-8229-3953-3. OCLC 494311843.

- Erdmans, Mary Patrice. "Immigrants and ethnics: Conflict and identity in Chicago Polonia." Sociological Quarterly 36.1 (1995): 175-195. online

- Erdmans, Mary Patrice (1998). Opposite Poles: Immigrants and Ethnics in Polish Chicago, 1976–1990. University Park, Pa: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01735-X. OCLC 37245940.

- Esslinger, Dean R. . Immigrants and the city: Ethnicity and mobility in a nineteenth century Midwestern community (Kennikat Press, 1975); focus on demography and social mobility of Germans, Poles, and other Catholics in South Bend

- PhD version University of Notre Dame ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1972. 7216267.

- Gladsky, Thomas S. (1992). Princes, Peasants, and Other Polish Selves: Ethnicity in American Literature. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 0-87023-775-6. OCLC 24912598. Archived from the original on 2011-01-11. Retrieved 2017-09-08.

- Greene, Victor. "Poles" in Thernstrom, Stephan; Orlov, Ann; Handlin, Oscar, eds. Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups. ISBN 0674375122. (Harvard University Press, 1980) pp 787–803

- Gurnack, Anne M., and James M. Cook. "Polish Americans, Political Partisanship and Presidential Elections Voting: 1972-2020." European Journal of Transformation Studies 9.2 (2021): 30-39. online

- Jackson, David J. (2003). "Just Another Day in a New Polonia: Contemporary Polish-American Polka Music". Popular Music & Society. 26 (4): 529–540. doi:10.1080/0300776032000144986. ISSN 0300-7766. OCLC 363770952. S2CID 194105509.

- Jaroszyńska-Kirchmann, Anna D. The exile mission: The Polish political diaspora and Polish Americans, 1939-1956 (Ohio University Press, 2004).

- Jones, J. Sydney. "Polish Americans." Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America, edited by Thomas Riggs, (3rd ed., vol. 3, Gale, 2014), pp. 477–492.

- Lopata, Helena Znaniecka (1976). Polish Americans: Status Competition in an Ethnic Community. Ethnic groups in American life series. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-686436-8. OCLC 1959615.

- Majewski, Karen (2003). Traitors and True Poles: Narrating a Polish-American Identity, 1880–1939. Ohio University Press Polish and Polish-American studies series. Athens: Ohio University Press. ISBN 0-8214-1470-4. OCLC 51895984.

- Mello, Caitlin. "Polish Immigration to Chicago and the Impact on Local Society and Culture." Language, Culture, Politics. International Journal 1.5 (2020): 183-193. online

- Nowakowski, Jacek (1989). Polish-American Ways. New York: Perennial Library. ISBN 0-06-096336-0. OCLC 20130171.

- Pacyga, Dominic A. "Poles," in Elliott Robert Barkan, ed., A Nation of Peoples: A Sourcebook on America's Multicultural Heritage (1999) pp 428–45

- Pacyga, Dominic A. "To live amongst others: Poles and their neighbors in industrial Chicago, 1865-1930." Journal of American Ethnic History 16#1 (1996): 55-73.online

- Pacyga, Dominic A. Polish immigrants and industrial Chicago: Workers on the south side, 1880-1922 (University of Chicago Press, 2003).

- Pacyga, Dominic A. American Warsaw: the rise, fall, and rebirth of Polish Chicago (University of Chicago Press, 2019).

- Pienkos, Donald E. PNA: A Centennial History of the Polish National Alliance of the United States (Columbia University Press, 1984) online

- Pienkos, Donald E. For your freedom through ours : Polish-American efforts on Poland's behalf, 1863-1991 (1991) online

- Pienkos, Donald E. "Of Patriots and Presidents: America's Polish Diaspora and U.S. Foreign Policy since 1917," Polish American Studies 68 (Spring 2011), 5–17.

- Pula, James S. (1995). Polish Americans: An Ethnic Community. Twayne's immigrant heritage of America series. New York: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-8427-6. OCLC 30544009.

- Pula, James S. (1996). "Image, Status, Mobility and Integration in American Society: The Polish Experience". Journal of American Ethnic History. 16 (1): 74–95. ISSN 0278-5927. OCLC 212041643.

- Pula, James S. "Polish-American Catholicism: A Case Study in Cultural Determinism", U.S. Catholic Historian Volume 27, #3 Summer 2009, pp. 1–19; in Project MUSE

- Radzilowski, John. "A Social History of Polish-American Catholicism", U.S. Catholic Historian – Volume 27, #3 Summer 2009, pp. 21–43 online

- Silverman, Deborah Anders (2000). Polish American Folklore. Urbana: Univ. of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02569-5. OCLC 237414611.

- Sugrue, Thomas. Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (Princeton University Press, 2005). online

- Swastek, Joseph. "The Poles in South Bend to 1914." Polish American Studies 2.3/4 (1945): 79–88.

- Tentler, Leslie Woodcock. “Who Is the Church?: Conflict in a Polish Immigrant Parish in Late Nineteenth-Century Detroit.” Comparative Studies in Society and History vol. 25 (April 1983): 241-276.

- Thomas, William Isaac; Znaniecki, Florian Witold (1996) [1918–1920]. The Polish Peasant in Europe and America: A Classic Work in Immigration History. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06484-4. OCLC 477221814.

- Wrobel, Paul. Our Way: Family, Parish, and Neighborhood in a Polish-American Community (University of Notre Dame Press, 1979).

Memory and historiography

edit- Jaroszynska-Kirchmann, Anna D., "The Polish American Historical Association: Looking Back, Looking Forward," Polish American Studies, 65 (Spring 2008), 57–76.

- Pietrusza, David Too Long Ago: A Childhood Memory. A Vanished World, Scotia (NY): Church and Reid Books, 2020.

- Radzialowski, Thaddeus C. "The View From a Polish Ghetto. Some Observations on the First One Hundred Years in Detroit" Ethnicity 1#2 (July 1974): 125-150. online

- Walaszek, Adam. "Has the" Salt-Water Curtain" Been Raised Up? Globalizing Historiography of Polish America." Polish American Studies 73.1 (2016): 47-67.

- Wytrwal, Joseph Anthony (1969). Poles in American History and Tradition. Detroit: Endurance Press. OCLC 29523.

- Zurawski, Joseph W. "Out of Focus: The Polish American Image in Film," Polish American Studies (2013) 70#1 pp. 5–35 in JSTOR

- Zurawski, Joseph W. (1975). Polish American History and Culture: A Classified Bibliography. Chicago: Polish Museum of America. OCLC 1993061.

External links

edit- PolishMigration.org, immigration records to United States between 1834 through 1897

- Chicago Foreign Language Press Survey: English translations of 120,000 pages of newspaper articles from Chicago's foreign-language press from 1855 to 1938, many from Polish papers