In Hawaiian religion, Pele (pronounced [ˈpɛlɛ]) is the goddess of volcanoes and fire and the creator of the Hawaiian Islands. Often referred to as "Madame Pele" or "Tūtū Pele" as a sign of respect, she is a well-known deity within Hawaiian mythology and is notable for her contemporary presence and cultural influence as an enduring figure from ancient Hawaii.[1] Epithets of the goddess include Pele-honua-mea ('Pele of the sacred land') and Ka wahine ʻai honua ('The earth-eating woman').[2]

| Pele | |

|---|---|

Goddess of Volcanoes and Fire | |

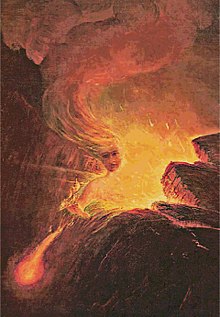

Pele by D. Howard Hitchcock, c. 1929 | |

| Abode | Halemaʻumaʻu |

| Symbol | fire, volcano |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | Haumea Ku-waha-ilo |

| Siblings | Hiʻiaka Nāmaka Kapo Kamohoalii Kāne Milohai |

In different stories talking about the goddess Pele, she was born from the female spirit named Haumea, a descendant of Papa, or Earth Mother, and Wakea, Sky Father, both descendants of the supreme beings. Pele is also known as "She who shapes the sacred land," known to be said in ancient Hawaiian chants.[3][4] The first published stories about Pele were written down by William Ellis.[5]: 5

Legends

editKīlauea is a currently active volcano that is located on the island of Hawaiʻi and is still being extensively studied.[6] Many Hawaiians believe Kilauea to be inhabited by a "family of fire gods," one of the sisters being Pele who is believed to govern Kilauea and is responsible for controlling its lava flows.[7] There are several traditional legends associated with Pele in Hawaiian mythology. In addition to being recognized as the goddess of volcanoes, Pele is also known for her power, passion, jealousy, and capriciousness. She has numerous siblings, including Kāne Milohai, Kamohoaliʻi, Nāmaka, and numerous sisters named Hiʻiaka, the most famous being Hiʻiakaikapoliopele (Hiʻiaka in the bosom of Pele). They are usually considered to be the offspring of Haumea. Pele's siblings include deities of various types of wind, rain, fire, ocean wave forms, and cloud forms. Her home is believed to be the fire pit called Halemaʻumaʻu at the summit caldera of Kīlauea, one of the Earth's most active volcanoes, but her domain encompasses all volcanic activity on the Big Island of Hawaiʻi.[8]

Pele shares features similar to other malignant deities inhabiting volcanoes, as in the case of the devil Guayota of Guanche Mythology in the Canary Islands, living on the volcano Teide and considered by the aboriginal Guanches as responsible for the eruptions of the volcano.[9]

Legend told that Pele herself journeyed on her canoe from the island of Tahiti to Hawaiʻi. When on her journey, it was said she tried to create her fires on different islands, but her sister, Nāmaka, was chasing her, wanting to put an end to her. In the end, the two sisters fought each other and Pele was killed. With this happening, her body was destroyed but her spirit lives in Halemaʻumaʻu on Kilauea. They say, "Her body is the lava and steam that comes from the volcano. She can also change form, appearing as a white dog, old woman, or beautiful young woman."[10]

In addition to her role as goddess of fire and her strong association with volcanoes, Pele is also regarded as the "goddess of the hula."[11] She is a significant figure in the history of hula because of her sister Hiʻiaka, who is believed to be the first person to dance hula.[12] As a result of Pele's significance in hula, there have been many hula dances and chants dedicated to her and her family. With hula being dedicated to Pele, the dance is often performed in a way that represents her intense personality and the movement of volcanoes.[13]

Expulsion version

editIn one version of the story, Pele is the daughter of Kanehoalani and Haumea in the mystical land of Kuaihelani, a floating free land like Fata Morgana. Kuaihelani was in the region of Kahiki (Kukulu o Kahiki). She stays close to her mother's fireplace with the fire-keeper Lono-makua. Her older sister Nā-maka-o-Kahaʻi, a sea goddess, fears that Pele's ambition would smother the homeland and drives Pele away. Kamohoali'i takes Pele south in a canoe called Honua-i-a-kea, along with her younger sister Hiʻiaka and with her brothers Kamohoaliʻi, Kane-milo-hai, Kane-apua, arriving at the islets above Hawaii. There Kane-milo-hai is left on Mokupapapa, just a reef, to build it up in fitness for human residence. On Nihoa, 800 feet above the ocean, Pele leaves Kane-apua after her visit to Lehua and after crowning a wreath of kau-no'a. Pele feels sorry for her younger brother and picks him up again. Pele used the divining rod, Pa‘oa, to pick a new home. A group of chants tells of a pursuit by Namakaokahaʻi, who tears Pele apart. Her bones, KaiwioPele, form a hill on Kahikinui, while her spirit escaped to the island of Hawaiʻi.[14]

Flood version

editIn another version, Pele comes from a land said to be "close to the clouds," with parents Kane-hoa-lani and Ka-hina-liʻi, and brothers Ka-moho-aliʻi and Kahuila-o-ka-lani. From her husband Wahieloa (also called Wahialoa) she has a daughter, Laka, and a son Menehune. Pele-kumu-honua entices her husband and Pele travels in search of him. The sea pours from her head over the land of Kanaloa (perhaps the island now known as Kahoʻolawe) and her brothers say:

O the sea, the great sea!

Forth bursts the sea:

Behold, it bursts on Kanaloa!

The sea floods the land, then recedes; this flooding is called Kai a Kahinalii ("The sea of Ka-hina-liʻi"), as Pele's connection to the sea was passed down from her mother Kahinalii.[14][15][16]

Pele and Poliʻahu

editPele is considered to be a rival of the Hawaiian goddess of snow, Poliʻahu, and her sisters Lilinoe (a goddess of fine rain), Waiau (goddess of Lake Waiau), and Kahoupokane (a kapa-maker whose kapa-making activities create thunder, rain, and lightning). All except Kahoupokane reside on Mauna Kea. The kapa-maker lives on Hualalai.

One myth tells that Poliʻahu had come from Mauna Kea with her friends to attend sled races down the grassy hills south of Hamakua. Pele came disguised as a beautiful stranger and was greeted by Poliʻahu. However, Pele became jealously enraged at the goddess of Mauna Kea. She opened the caverns of Mauna Kea and threw fire from them towards Poliʻahu, with the snow goddess fleeing towards the summit. Poliʻahu was finally able to grab her now-burning snow mantle and throw it over the mountain. Earthquakes shook the island as the snow mantle unfolded until it reached the fire fountains, chilling and hardening the lava. The rivers of lava were driven back to Mauna Loa and Kīlauea. Later battles also led to the defeat of Pele and confirmed the supremacy of the snow goddesses in the northern portion of the island, and Pele in the southern portion.[17]

Pele, Hiʻiaka, and Lohiʻau

editIn one account of the Pele myths, she is banished from her home in Tahiti for creating hot spots by her older sister, Namakaokahaʻi, who also convinced the rest of her family that Pele would burn them all. Then, Pele travels on the canoe Honuaiakea to find a new home with her brother Kamohoaliʻi. Her mother gave her an egg to take care of and it later hatches into a baby girl whom Pele names Hiʻiaka-i-ka-poli-o-pele (Hiʻiaka in the Bosom of Pele) or Hiʻiaka for short. She is her favorite sister and encouraged her to befriend the people of Puna. However, when Hiʻiaka became best friends with a girl named Hōpoe, Pele became jealous of their friendship. Pele saw Lohiʻau, a chief of Kauaʻi, in a dream, sending Hiʻiaka to bring him to her in forty days or else she would punish them. When Hiʻiaka seeks out Lohiʻau, she discovers he is dead but she calls upon the power of the sorcery goddess Uli to revive him.[18] As Hiʻiaka is on her journey, Pele grows impatient and sends a lava flow to Hōpoe's home before the forty days were up. When Hiʻiaka returns to Hawaiʻi with Lohiʻau, she saw Hōpoe covered in stone and knew Pele was behind this. Hiʻiaka spitefully embraced Lohiʻau in Pele's view, which further angered Pele, who then covered Lohiʻau with lava as well. The sisters saw that their anger led to the death of the two people who meant the most to them, so Pele apologetically brought Lohiʻau back to life and let him decide whom he would choose. Unfortunately for Pele, Lohiʻau ended up choosing Hiʻiaka, yet Pele gave them both her blessing.[19]

In another version of the myth, Pele hears the beating of drums and chanting coming from Kauaʻi while she is sleeping and travels there in her spirit form. She disguises herself as a beautiful young woman and meets Lohiʻau in this way. After three days of making love together, Pele goes back to Hawaiʻi and Lohiʻau dies from a broken heart.[20]

Modern times

editBelief in Pele continued after the old religion was officially abolished in 1819. In the summer of 1823 English missionary William Ellis toured the island to determine locations for mission stations.[21]: 236 After a long journey to the volcano Kīlauea with little food, Ellis eagerly ate the wild berries he found growing there.[21]: 128 The berries of the ʻōhelo (Vaccinium reticulatum) plant are considered sacred to Pele. Traditionally prayers and offerings to Pele were always made before eating the berries. The volcano crater was an active lava lake, which the natives feared was a sign that Pele was not pleased with the violation.[21]: 143 Although wood carvings and thatched temples were easily destroyed, the volcano was a natural monument to the goddess.

In December 1824 the High Chiefess Kapiʻolani descended into Halemaʻumaʻu after reciting a Christian prayer instead of the traditional Hawaiian one to Pele. As it was predicted, she survived and this story was often told by missionaries to show the superiority of their faith.[22] Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892) wrote a poem about the incident in 1892.[23]

An urban legend states that Pele herself occasionally warns locals of impending eruptions. Appearing in the form of either a beautiful young woman or an elderly woman with white hair, sometimes accompanied by a small white dog, and always dressed in a red muumuu, Pele is said to walk along the roads near Kīlauea, but will vanish if passersby stop to help her, similar to the Resurrection Mary or vanishing hitchhiker legend. The passerby is then obliged to warn others or suffer misfortune in the next eruption. Another legend, Pele's Curse, states that Pele's wrath will fall on anyone who removes items from her island. Every year numerous small natural items are returned by post to the National Park Service by tourists seeking Pele's forgiveness. It is believed Pele's Curse was invented in the mid-20th century to deter tourist depredation.[24]

When businessman George Lycurgus ran a hotel at the rim of Kīlauea, called the Volcano House from 1904 through 1921, he would often "pray" to Pele for the sake of the tourists. Park officials frowned upon his practices of tossing items, such as gin bottles (after drinking their contents), into the crater.[25]

William Hyde Rice included an 11-page summary of the legends of Pele in his 1923 collection of Hawaiian legends, a reprint of which is available online from the Bernice P. Bishop Museum's Special Publications section.[26]

In 2003 the Volcano Art Center had a special competition for Pele paintings to replace one done in the early 20th century by D. Howard Hitchcock displayed in the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park visitors center. The existing portrait of what looked like a blond Caucasian as the Hawaiian goddess had been criticized by many Native Hawaiians.[27] Over 140 paintings were submitted, and finalists were displayed at sites within the park.[28] The winner of the contest was artist Arthur Johnsen of Puna.[29] This version shows the goddess in shades of red, with her digging staff Pāʻoa in her left hand, and an embryonic form of her sister goddess Hiʻiaka in her right hand.[30] The painting is now on display at the Kilauea Visitor Center.[31]

The religious group Love Has Won briefly moved to Hawaii and sparked violent protests from locals after claiming their founder Amy Carlson was Pele. [32]

Pele is among the gods and goddesses depicted in Walt Disney's Enchanted Tiki Room at the Disney Parks. She is voiced by Ginny Tyler.

Relatives

editPele's other prominent relatives are:

- Ai-kanaka, friend[18]

- Ahu-i-maiʻa-pa-kanaloa, brother, name translates to "banana bunch of Kanaloa's field"[18]

- Haumea (mythology), mother of Pele

- Hiʻiaka or Hiʻiaka-i-ka-pua-ʻena-ʻena, sister, spirit of the dance, lei maker, healer[18]

- Hina-alii, mother and takes different forms

- Ka-maiau, war god, relative to Pele and Hiʻiaka[18]

- Kā-moho-aliʻi, a shark god and the keeper of the water of life

- Kane-ʻapua, demigod younger brother[18]

- Kamapuaʻa, a shapeshifting kupua and a recurring figure in Hawaiian folklore, sometimes described as the consort of Pele

- Kane-Hekili, spirit of the thunder (a hunchback)

- Kane-hoa-lani, father and division with fire

- Kaʻōhelo, a mortal sister

- Kapo, a goddess of fertility

- Ka-poho-i-kahi-ola, spirit of explosions

- Ke-ō-ahi-kama-kaua, the spirit of lava fountains (a hunchback)

- Ke-ua-a-ke-pō, spirit of the rain and fire

- Nāmaka, appeared as a sea goddess or water spirit in pele cycle sister of Pele

- Tama-ehu, brother, god of salamanders and fire in Tahitian[18]

- Ulupoka, enemy from Polynesian Mythology

- Wahieloa, husband which she fathered sons Laka and Menehune[18]

Chants

edit Lapakū ka wahine a‘o Pele i Kahiki |

Pele is active in Tahiti |

| —[33] |

Mai ka Lua a‘u i hele mai nei, mai Kīlauea, |

From the crater I’ve come, from Kīlauea, |

| —[33] |

Both of the chants above were performed at Halemaʻumaʻu, where it is said Pele currently resides.

Other data

editPele shares features similar to other malignant deities inhabiting volcanoes, as in the case of the devil Guayota of Guanche Mythology in Canary Islands (Spain), living on the volcano Teide and was considered by the aboriginal Guanches as responsible for the eruptions of the volcano.[34]

In geology

editSeveral phenomena connected to volcanism have been named after her, including Pele's hair, Pele's tears, and Limu o Pele (Pele's seaweed). A volcano on the Jovian moon Io is also named Pele.[35]

Myths about Pele encode dateable natural events.[36]: 22 The chronology of Pele’s journey corresponds with the geological age of the Hawaiian islands.[5]: 19

In 2006, one volcanologist suggested the battle between Pele and Hiʻiaka was inspired by geological events around 1500 AD.[5]: 49

See also

edit- Painting of Pele

- Ti'iti'i, god of fire in Samoan mythology.

- Mahuika, goddess of fire in Māori mythology.

- Rūaumoko, god of earthquakes, volcanoes and seasons in Māori mythology.

- Vulcan, ancient Roman god of fire

- Aganju, god of volcanoes in the Lucumi/santeria religion

References

edit- ^ 'Iolana, Patricia (2006). "TuTu Pele: The Living Goddess of Hawaiʻi's Volcanoes". Sacred History.

- ^ H. Arlo Nimmo (2011). Pele, Volcano Goddess of Hawai'i: A History. McFarland. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-7864-6347-3.

- ^ Wong, Alia (11 May 2018). "Madame Pele's Grip on Hawaii". The Atlantic. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ "Pele – Goddess of Fire" Archived 2017-03-26 at the Wayback Machine. Coffee Times, retrieved on 8 April 2018.

- ^ a b c Nimmo, H. Arlo (2011-10-14). Pele, Volcano Goddess of Hawai'i: A History. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-8653-3.

- ^ Donald A. Swanson, "Hawaiian oral tradition describes 400 years of volcanic activity at Kilauea,"Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal 176 (2008): 427-431. https://pages.mtu.edu/~raman/papers2/SwansonKilaueaMythsJVGR08.pdf. Retrieved on 6-Apr-2018.

- ^ Martha Warren Beckwith, Hawaiian Mythology (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1970).

- ^ William Westervelt (1999). Hawaiian Legends of Volcanoes. Mutual Publishing, originally published 1916 by Ellis Press.

- ^ Ethnografia y anales de la conquista de las Islas Canarias

- ^ "Who is the goddess of Pele and how is she related to the origin of the Hawaiian Islands?" Oregon State University System website, https://volcano.oregonstate.edu/who-goddess-pele-and-how-she-related-origin-hawaiian-islands Archived 2021-04-21 at the Wayback Machine, N/A, retrieved on 9 April 2018.

- ^ H. Arlo Nimmo. "Pele, Ancient Goddess of Contemporary Hawaii," Pacific Studies vol. 9, no. 2 (1986): 158-159. https://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/PacificStudies/id/1232/rec/18. Retrieved on 9 April 2018.

- ^ H. Arlo Nimmo. "Pele, Ancient Goddess of Contemporary Hawaii," Pacific Studies vol. 9, no. 2 (1986): 158-159. https://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/PacificStudies/id/1232/rec/18. Retrieved on 6 April 2018.

- ^ "Ancient Hula Types Database," Hula Preservation Society. Retrieved on 6 April 2018. https://www.hulapreservation.org/hulatype.asp?ID=18 Archived 2021-04-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Martha Warren Beckwith (1940). Hawaiian Mythology. Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1-60506-957-9.

- ^ name="FStS">Nicholson, Henry Whalley (1881). From Sword to Share; Or, A Fortune in Five Years at Hawaii. London, England: W.H. Allen and Co. pp. 39.

Behold, it bursts on Kanaloa!.

- ^ "Pele and the Deluge," Access Genealogy Hawaiian Folk Tales A Collection of Native Legends [1], 1907, Retrieved on 24 October 2012.

- ^ W. D. Westervelt, Hawaiian legends of volcanoes. Boston, G.H. Ellis Press, 1916.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Schrempp, Gregory; Craig, Robert D. (1991). "Dictionary of Polynesian Mythology". The Journal of American Folklore. 104 (412): 231. doi:10.2307/541247. ISSN 0021-8715. JSTOR 541247.

- ^ Varez, Dietrich (1991). Pele, the fire goddess. Bishop Museum Press. ISBN 0930897528. OCLC 25687609.

- ^ Andrade, Carlos. Ha'ena : through the eyes of the ancestors. ISBN 9780824868826. OCLC 986668949.

- ^ a b c William Ellis (1823). A journal of a tour around Hawai'i, the largest of the Sandwidch Islands. Crocker and Brewster, New York, republished 2004, Mutual Publishing, Honolulu. ISBN 1-56647-605-4.

- ^ Penrose C. Morris (1920). "Kapiolani". All About Hawaii: Thrum's Hawaiian Annual and Standard Guide. Thomas G. Thrum, Honolulu: 40–53.

- ^ Alfred Lord Tennyson (1899). Hallam Tennyson (ed.). The life and works of Alfred Lord Tennyson. Vol. 8. Macmillan. pp. 261–263. ISBN 0-665-79092-9.

- ^ Cart, Julie; Times, Los Angeles (17 May 2001). "Hawaii's hot rocks blamed by tourists for bad luck / Goddess said to curse those who take a piece of her island". SFGate. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ "The Volcano House". Hawaii Nature Notes. 5 (2). National Park Service. 1953.

- ^ William Hyde Rice, preface by Edith J. K. Rice (1923). "Hawaiian Legends" (PDF). Bulletin 3. Bernice P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- ^ Rod Thompson (July 13, 2003). "Rendering Pele: Artists gather paints and canvas in effort to be chosen as Pele's portrait maker". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- ^ "Visions of Pele, the Hawaiian Volcano Deity" (PDF). Press release on Volcano Art Center Gallery web site. August 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-05. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- ^ "Fresh face put on volcano park". The Honolulu Advertiser. August 16, 2003. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ Nimmo, H. Arlo (2011). Pele, Volcano Goddess of Hawai'i: A History. McFarland. p. 170. ISBN 9780786486533.

- ^ "Arthur Johnsen: Painter". Arthur Johnsen Gallery web site. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ Sam Tabachnik (11 September 2020). ""Cult-like" Colorado spiritual group met with violent protests during Hawaiian sojourn". Denver Post. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ a b Hoomanawanui, kuualoha (2014). Voices of fire : reweaving the literary lei of Pele and Hi'iaka. ISBN 9780816679225. OCLC 913842694.

- ^ Ethnografia y anales de la conquista de las Islas Canarias

- ^ Radebaugh, J.; et al. (2004). "Observations and temperatures of Io's Pele Patera from Cassini and Galileo spacecraft images". Icarus. 169 (1): 65–79. Bibcode:2004Icar..169...65R. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2003.10.019.

- ^ Piccardi, Luigi; Masse, W. Bruce (2007). Myth and Geology. Geological Society of London. ISBN 978-1-86239-216-8.