Mongolian Americans are American citizens who are of full or partial Mongolian ancestry. The term Mongol American is also used to include ethnic Mongol immigrants from groups outside of Mongolia as well, such as Kalmyks, Buryats, and people from the Inner Mongolia autonomous region of China.[8] Some immigrants came from Mongolia to the United States as early as 1949, spurred by religious persecution in their homeland.[7] However, Mongolian American communities today are composed largely of migrants who arrived after restrictions on emigration were lifted after the Mongolian revolution of 1990.[3][9][10]

Mongolian language in the United States | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 51,954 (2023)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 5,493[2] | |

| 4,000[3] | |

| 2,600[4] | |

| 2,000[5] | |

| Languages | |

| Mongolian, American English | |

| Religion | |

| Buddhism,[3] Christianity,[6][7] Tengrism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Kalmyk Americans[7] | |

Migration history and distribution

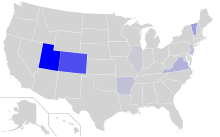

editThe Denver metropolitan area was one of the early focal points for the new wave of Mongolian immigrants.[6] Other communities formed by recent Mongolian immigrants include ones in Chicago, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C.[3] The largest Mongolian-American community in the United States is located in Los Angeles, California.[11]

Colorado

editThe Mongolian community in Denver originated in 1989, when Djab Burchinow, a Kalmyk American engineer, arranged for three junior engineers from Mongolia to study at the Colorado School of Mines. They were followed by four more students the following year; in 1991, Burchinow also began to urge the Economics Institute at the University of Colorado to admit Mongolian international students. By 1996, the Denver campus of the University of Colorado had set up a program specifically aimed at bringing Mongolian students to the state. The rising number of students coincided with an economic boom and labor shortage in and around Denver, influencing many Mongolian students to stay in Colorado after their graduation, though a significant number did return to Mongolia—and in 2003 formed a Mongolian association of former Coloradan students (their influence may be seen in the name of the street on which the United States embassy in Ulaanbaatar stands: "Denver Street").[6][12] As of 2006[update], Colorado's Mongolian population was believed to be about 2,000 people, according to the director of a community-run Mongolian language school established by parents worried about the increasing Americanization of their children.[5]

California

edit5,000 people of Mongolian origin live in the state of California.[2] As many as 3,000 of these live in the San Francisco Bay Area's East Bay cities of Oakland and San Leandro; they began settling in the area only after 2002, and thus their presence was not noted in the 2000 Census. Many live in predominantly Chinese American and Vietnamese American neighborhoods; tensions arose between these recent immigrants and the older immigrant communities, with occasional violence between Mongolian and other Asian American youths.[13] In one major incident, a Mongolian immigrant girl was shot dead in a confrontation between Southeast Asian and Mongolian youths in an Alameda park on Halloween night in 2007.[14][15] Four members of the former group were convicted of first-degree murder: three of the boys were tried in juvenile court and sentenced to seven years in prison in 2008, while the shooter was tried as an adult and sentenced to 50 years to life in state prison in 2010.[16][17]

The Mongolian immigrant population in Los Angeles is estimated at 2,000 people as of 2005[update], according to local community leader Batbold Galsansanjaa (1964 - 2012).[18][19][20] He had immigrated to America in 1999, with his wife and two children. In 2000, Galsansanjaa established the first Los Angeles Mongolian Community, a nonprofit organization, and later guided over 2,000 Mongolian immigrants with advice on obtaining Social Security numbers, driver's licenses, housing, and other concerns. These Mongolians have close ties to the Korean American community in Los Angeles. Most of the Mongolian immigrants live and work in "Koreatown". A Korean who had been a missionary in Mongolia established Los Angeles's only Mongolian-speaking church in Koreatown. And a Mongolian Buddhist congregation gathers for worship at the nearby Korean Buddhist Kwan-Um Temple.[21]

Maryland

editPrior to the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, restrictive covenants were used in the Washington, D.C. suburb of Bethesda, Maryland, to exclude racial and ethnic minorities, including Mongolian Americans and other Asian Americans.[22] A 1938 restrictive covenant in the Bradley Woods subdivision of Bethesda states: "No part of the land hereby conveyed, shall ever be used, or occupied by or sold, demised, transferred, conveyed, unto, or in trust for, leased, or rented, or given to negroes, or any person or persons of negro blood or extraction or to any person of the Semitic Race, blood, or origin, which racial description shall be deemed to include Armenians, Jews, Hebrews, Persians, Syrians, Greeks and Turks, or to any person of the Mongolian Race, blood, or origin, which racial description shall be deemed to include Chinese, Japanese, and Mongolians, except that this paragraph shall not be held to exclude partial occupancy of the premises by domestic servants of the purchaser or purchasers."[23]

Virginia

editThe Mongolian embassy to the United States estimated the Mongolian population in nearby Arlington, Virginia, at 2,600 as of 2006[update]; reportedly, they were attracted to the area by the high quality of public education—resulting in Mongolian becoming the school system's third-most spoken language, after English and Spanish; 219 students of Mongolian background are enrolled in the local school system, making up 1.2% of all students, but often forming a majority in ESL classes. Members of the first generation largely come from university-educated backgrounds in Mongolia, but work at jobs below such qualifications after moving to the United States. Community institutions include an annual children's festival and a weekly newspaper.[4]

Illinois

editThe Chicago metropolitan area's Mongolian American community is estimated at between 3,000 and 4,000 people by local leaders; they are geographically dispersed but possess well-organized mutual support networks. Some have established small businesses, while others work in trades and services, including construction, cleaning, housekeeping, and food service.[3] In 2004, Lama Tsedendamba Chilkhaasuren, an expatriate from Mongolia, came to the Chicago area for a planned stay of one year in an effort to build a temple for the area's Mongolian Buddhist community.[24] As of 2010, nearly 200 Mongolians lived in Skokie, Illinois.

Demographics

edit60% of Mongolians residing in the United States entered the country on student visas, 34% on tourist visas, and only 3% on working visas. 47% live with their family members. The Mongolian Embassy estimates that, up to 2007, only 300 babies have been born to Mongolian parents in the United States. Interest in migration to the United States remains high due to unemployment and low income levels in Mongolia; every day, fifty to seventy Mongolians attend visa interviews at the United States embassy in Ulaanbaatar.[25] From 1991 to 2011, 5,034 people born in Mongolia became permanent residents of the United States, the vast majority in the mid-to-late-2000s; the annual number peaked at 831 in 2009.[26][27]

The Mongolian population has increased from roughly 6,000 in the year 2000 to 18,000 in 2010 and 21,000 in 2015.[28]

In Clark County, Indiana (particularly Jeffersonville) Mongolians are the 5th largest Asian American population according to the 2020 census and possibly number in the hundreds.[29]

As of 2013, there were 1361 international students of Mongolian origin studying in the United States.[30]

Culture and community

editA number of Mongol cultural associations exist across the United States, including but not limited to the Mongolia Society;[31] Mongolian Cultural Association at the University of Michigan.[32]

The Mongol-American Cultural Association (MACA) was created to preserve and promote Mongol culture in the United States. MACA understands the term Mongol to be inclusive of the people and cultures of all regions where Mongol groups have traditionally lived; in addition to Mongolia, it includes the people and cultures of Kalmykia, Buryatia, Tuva and the Mongol regions of China. MACA was founded in 1987 by the late Professor Gombojab Hangin, Indiana University, and Tsorj Lama, former Abbot of the Qorgho Monastery in Western Sunid, Southern Mongolia. Since the death of Professor Hangin in 1989, and of Tsorj Lama in 1991, their students have carried on the work they started. Current board members are Tsagaan Baatar, Chinggeltu Borjiged, Enghe Chimood, Tony Ettinger, Palgi Gyamcho, and Sanj Altan. MACA was formally incorporated as a 501C3 non-profit organization in 1992.

MACA also pursues a humanitarian program. In 1994, MACA sent $10,000 worth of insulin to Mongolia. MACA was an early supporter of the Peace Corps programs in Mongolia with their English language instructional materials needs. In 1995, MACA established the Mongolian-Children's Aid and Development Fund (MCADF) which functioned as the fund raising and executive arm of the various humanitarian initiatives aimed at providing aid to Mongolian children. Former Secretary of State James A. Baker III serves as honorary chairman of the advisory board to the MCADF. The MCADF has provided nutritional aid and clothing to orphanages and provided small stipends to selected orphans. From 2004 to 2008, the MCADF sponsored the Night Clinic operated by the Christina Noble Foundation, which provides medical services to the street children of Ulaanbaatar. MACA is a primary sponsor of the Injannashi Fund, which provides small educational grants to students in Southern Mongolia. MACA also provides small grants from time to time to cultural and educational institutions to support cultural events related to the Mongolias. In 2011, the MCADF provided a grant to assist the Wildlife Conservation Fund with its 'Trunk' program in Mongolia, which aims to educate school age children on the importance of wildlife and environment.

MACA holds a Chinggis Qan ceremony annually, a continuation of the Chinggis Qan memorial held in the Ezen Qoroo region of Ordos. This ritual was started in the United States by teachers Gombojab Hangin and C'orj'i Lama in 1988, and is held annually in late fall. In 1999, to mark the 10th anniversary of the death of Professor Gombojab Hangin, a Chinggis Qan Symposium was held in his memory, which resulted in the publication of the proceedings with articles from scholars from Mongolia, Southern Mongolia, Buryatia, and Kalmykia. In 2012, MACA celebrates 25 years of the ceremony in the United States.

MACA is open to all individuals who share a common belief in the importance of preserving Mongol culture in the United States.

Notable people

edit- Avani Gregg, social media personality[33]

- Diluwa Khutugtu Jamsrangjab

- Alex Borstein, actress[34]

- Oyuna Uranchimeg, wheelchair curler for Team USA at the 2022 Paralympics

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "US Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 21, 2024.

- ^ a b "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Census Summary File 2, Mongolian alone or in any combination (465) & (100-299) or (300, A01-Z99) or (400-999)". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Steffes, Tracy (2005). "Mongolians". The Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- ^ a b Bahrampour, Tara (July 3, 2006). "Mongolians Meld Old, New In Making Arlington Home". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- ^ a b Lowrey, Brandon (August 13, 2006). "Keeping heritage in mind". Denver Post. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- ^ a b c Cayton-Holland, Adam (July 6, 2006). "Among the Mongols: Steppe by steppe, the hordes are descending on Denver". Denver Westword News. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

- ^ a b c Ts., Baatar (1999). "Social and cultural change in the Mongol-American community" (PDF). Anthropology of East Europe Review. 17 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 11, 2004.

- ^ "Mongolian Americans". encyclopedia.com. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ RT UK (August 7, 2015). "Steven Seagal: "I'm a Russian Mongol"". Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ ""Таких храмов, как этот, я не видел никогда в своей жизни" » Сохраним Тибет! - Тибет, Далай-лама, буддизм". savetibet.ru. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Aghajanian, Liana. "Will Mongolia's Boom Cost Los Angeles Its Growing Immigrant Community?". The Atlantic Cities. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- ^ US Embassy in Mongolia - Contact Us Page https://mongolia.usembassy.gov/contact.html

- ^ Murphy, Kate (April 6, 2007). "Recreation center plans party to bridge ethnic gap; Chinese-American attacked by Mongolian youths in Oakland's Chinatown". Oakland Tribune. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Albert, Mark (June 27, 2008). "One Shooter or Two in Iko Slaying? Prosecution stumbles over witness testimony". Alameda Sun. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Lee, Min (December 18, 2007). "Police Accused of Racial Profiling in Alameda Murder Investigation". New American Media. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Lee, Henry K. (January 26, 2008). "3 boys sentenced in Alameda Halloween killing". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ "Gunman Sentenced In Alameda Teen Halloween Slaying". KTVU. August 20, 2010. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Kang, K. Connie (November 26, 2005). "L.A.'s Christian Mongolians Find Home at Church". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ Batbold Galsansanjaa

- ^ "Los Angeles Mongolian Cyber Community - Next Step Шинэ Жилийн Цэнгүүн - IMG_1070". lamongols.com. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ Tang, K. Connie (November 26, 2005). "L.A.'s Christian Mongolians Find Home at Church". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ "Was your home once off-limits to non-Whites? These maps can tell you". Washington Post. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ^ "Bradley Woods, Block 4 (Resubdivision)". Montgomery Planning. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ^ Avila, Oscar (March 19, 2004). "Buddhist priest lights way: City's Mongolians aim to form temple, cultural identity". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Solongo, Algaa (May 25, 2007). Growth of Internal and International Migration in Mongolia (PDF). 8th International Conference of Asia Pacific Migration Research Network. Fujian, China: Fujian Normal University.

- ^ "Table 3: Immigrants admitted by region and country of birth: fiscal years 1989-2001" (Excel spreadsheet). Statistical Yearbook. Immigration and Naturalization Service. 2001. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ^ "Table 3: Persons Obtaining Legal Permanent Resident Status by Region and Country of Birth: Fiscal Years 2002 to 2011" (Excel spreadsheet). Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. 2011. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ^ "Mongolians in the U.S. Fact Sheet". Pew Research Center. 2015. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ "Inside the Diverse and Growing Asian Population in the U.S." The New York Times. August 21, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ TOP 25 PLACES OF ORIGIN OF INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS Institute of International Education

- ^ "The Mongolia Society". Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ "The Mongolian Cultural Association at the University of Michigan". Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Williams, Kori (April 28, 2020). "Here's Everything You Need to Know About TikTok Star Avani Gregg". Seventeen. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Stern, Marlow (November 12, 2013). "'Family Guy' Star Alex Borstein Is Ready for Her HBO Close-Up". The Daily Beast. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

Further reading

edit- Lee, Jonathan H. X.; Nadeau, Kathleen M. (2011). "Mongolian Americans". Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 811–850. ISBN 9780313350665.

- Tsend, Baatar. "Mongolian Americans." Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America, edited by Thomas Riggs, (3rd ed., vol. 3, Gale, 2014), pp. 219–230. online

External links

edit- Mongolia Society

- Mongol American Cultural Association

- Kalmyk American Cultural Association

- Mongolian Immigrant Tries to Find New Life, 1991 article in The New York Times about a homeless Mongolian immigrant in New York