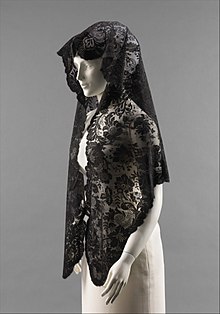

A mantilla is a traditional female liturgical lace or silk veil or shawl worn over the head and shoulders, often over a high hair ornament called a peineta, particularly popular with women in Spain and Latin America.[1] It is also worn by Catholic and Plymouth Brethren women around the world, Mennonite women in Argentina, and without the peineta by Eastern Orthodox women in Russia. When worn by Eastern Orthodox women the mantilla is often white, and is worn with the ends crossed over the neck and draped over the opposite shoulder. The mantilla is worn as a Christian headcovering by women during church services, as well as during special occasions.[2][3] A smaller version of the mantilla is called a toquilla.[4]

Blond mantillina. Valencian Museum of Ethnology. | |

| Type | Headgear |

|---|---|

| Material | Silk lace or tulle |

| Place of origin | Spain |

| Introduced | 16th century |

History

editThe lightweight ornamental mantilla came into use in the warmer regions of Spain towards the end of the 16th century, and ones made of lace became popular with women in the 17th and 18th centuries, being depicted in portraits by Diego Velázquez and Goya. With Spain being largely a Christian country, the mantilla is a Spanish adaption of the Christian practice of women wearing headcoverings during prayer and worship (cf. 1 Corinthians 11:2–10).[3]

As Christian missionaries from Spain entered the Americas, the wearing of the mantilla as a Christian headcovering was brought to the New World.[3] Fray Nicolás García Jerez, who in the 19th century served as the Bishop of Nicaragua and Costa Rica, as well as the Governor of Nicaragua, mandated that mantillas be opaque and not made of transparent lace; women who continued to wear thin mantillas were excommunicated from the Catholic Church.[A][3]

In the 19th century, Queen Isabella II actively encouraged the use of the mantilla. The practice diminished after her abdication in 1870, and by 1900 the use of the mantilla became largely limited to church services, as well as formal occasions such as bullfights, Holy Week and weddings.[2]

In Spain, women still wear mantillas during Holy Week (the week leading to Easter), bullfights and weddings. Also a black mantilla is traditionally worn when a woman has an audience with the Pope and a white mantilla is appropriate for a church wedding, but can be worn at other ceremony occasions as well. In accordance with what is known as the privilège du blanc, only the queen of Spain and selected other Catholic wives of Catholic sovereigns can wear a white mantilla during an audience with the Pope.

In Argentina, many women who are Mennonite Christians wear the mantilla as a Christian headcovering.[2] Traditional Catholic women and Plymouth Brethren women in various parts of the globe use it for the same purpose.[6]

Peineta

editA peineta, similar in appearance to a large comb, is used to hold up a mantilla. This ornamental comb, usually in tortoiseshell color, originated in the 19th century. It consists of a convex body and a set of prongs and is often used in conjunction with the mantilla. It adds the illusion of extra height to the wearer and also holds the hair in place when worn during weddings, processions and dances. It is a consistent element of some regional costumes of Valencia and Andalusia and it is also often found in costumes used in the Moorish and Romani people influenced music and dance called Flamenco.

-

Mexican women wearing the mantilla, painting by Carl Nebel, 1836

-

Raquel Meller, Spanish singer and actress, 1910

-

Raquel Meller with her husband, Enrique Gómez Carrillo, in the painting Venus of Poetry, 1913

-

Mantilla made of white lace, during a Holy Week procession in Spain, 2006.

See also

editReferences

editNotes

edit- ^ The early Christian Church's Apostolic Tradition specified that Christian headcovering is to be observed with an "opaque cloth, not with a veil of thin linen".[5]

Citations

edit- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language; 4th edition. 2000

- ^ a b c Schlabach, Theron F. (2 February 1999). Gospel Versus Gospel: Mission and the Mennonite Church, 1863-1944. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-57910-211-1.

- ^ a b c d Castañeda-Liles, María Del Socorro (2018). Our Lady of Everyday Life: La Virgen de Guadalupe and the Catholic Imagination of Mexican Women in America. Oxford University Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-19-028039-0.

The tradition of women's use of the mantilla could be traced back to Apostle Saint Paul's letters to the Corinthians where he states that it was a disgrace for women to attend sacred temples or prophesize with their heads uncovered. Women's public hair display inside sacred temples or when prophesizing was equated to having a shaven head, which was believed to be a disgrace to God. Accordingly, women's public hair display in church services was considered to be a serious violation that carried severe consequences. This belief was transplanted to Latin America through the colonizing efforts of Spanish missionaries who brought with them Pre-Tridentine Catholic practices and beliefs. For example, in the 19th century, Bishop Fray Nicolás García Jerez, Bishop of Nicaragua and Costa Rica and Governor of Nicaragua between 1811 and 1814, was among the gatekeepers of such mandates. He demanded that women who covered their head with a gauze mantilla or muslin so clear that, far from contributing to modesty and decorum, which according to him her sex must at all times embrace, only served to call attention to them as an idol of prostitution, a stumbling block, and spiritual distress (Lobo 2015). He ordered that women who chose to continue wearing transparent mantillas be thrown out of the Church and excommunicated.

- ^ O'Loughlin, R. S.; Montgomery, H. F.; Dwyer, Charles (1905). The Delineator, Volume 66. The Butterick Publishing Co. p. 335.

- ^ "On Head Coverings". Classical Christianity. 11 January 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

And let all the women have their heads covered with an opaque cloth, not with a veil of thin linen, for this is not a true covering. (Apostolic Tradition Part II.18)

- ^ Loop, Jennifer (12 May 2020). "Why I Keep My Headcovering". N. T. Wright. Retrieved 9 April 2022.