Islamic archaeology involves the recovery and scientific investigation of the material remains of past cultures that can illuminate the periods and descriptions in the Quran, and early Islam.[2] The science of archaeology grew out of the older multi-disciplinary study known as antiquarianism. The Egyptian "Antiquities Authority" was established in 1858 and remains a government organization which serves to protect and preserve the heritage and ancient history of Egypt.

Head of a man from Qaryat al-Faw (1st century BC) |

Early pioneers in Islamic archaeology included Eduard Glaser and Alois Musil. Khaled al-Asaad was principal custodian of the Palmyra site from 1963, overseeing its elevation to a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[3][4] Some of the earliest areas investigated in Saudi Arabia include Al Faw Village and Madain Saleh. Jodi Magness has covered the archaeology of early Islamic settlement in Palestine. The Museum of Islamic Archaeology and Art of Iran was opened in 1972. It houses tools dating back 30,000 to 35,000 years and crafted by Mousterian Neanderthals in Yafteh. Among the oldest human artifacts are 9,000-year-old and animal figurines from the Sarab mound in Kermanshah Province. The Gaza Museum of Archaeology was opened in 2008. Objects protected from display include Aphrodite in revealing gown, images of ancient deities and oil lamps featuring menorahs. Since 2016 the Al-Qasimi Professor of African and Islamic Archaeology at the University of Exeter, Timothy Insoll, has directed the Centre for Islamic Archaeology.[5] Insoll is on the editorial board of the Journal of Islamic Archaeology.

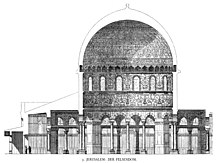

The oldest extant Islamic monument is The Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem which contains some of the earliest extant qurānic text, dated to 692CE. They vary from today's standard text (mainly changes from the first to the third person) and are mixed with pious inscriptions absent from the Quran.[6] During a six-week period in 1833, Frederick Catherwood produced the first known detailed survey.[1]

Pre-Islamic In-situ archaeology includes south Arabian 4th CE rock inscriptions that evidence fewer pagan expressions and the start in use of the monotheistic "rahmān".[6]

Fewer archaeological surveys have taken place in the Arabian peninsula and are considered taboo in Mecca (The Noble) and Medina (The Enlightened City). There is no architecture from the time of Mohammed in either city and the battlefields of the Quran have not been unearthed. Known settlements from the time, such as Khaybar, remain uninvestigated. Archaeologial evidence for Quranic narratives yet to be uncovered [6] include that for the ʿĀd who built monuments and strongholds at every high point[7] and their fate evident from the remains of their dwellings.[8][9]

A political dispute in the Uttar Pradesh city of Ayodhya, as noted by academic, K. K. Muhammed, has revolved around archaeological Issues: whether an archaeological plot, believed the temple birthplace of the Hindu deity Rama, was demolished or modified to create the Babri Masjid mosque.[10]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Drawings of Islamic Buildings: Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009.

Until 1833 the Dome of the Rock had not been measured or drawn; according to Victor von Hagen, 'no architect had ever sketched its architecture, no antiquarian had traced its interior design...' On 13 November in that year, however, Frederick Catherwood dressed up as an Egyptian officer and accompanied by an Egyptian servant 'of great courage and assurance', entered the buildings of the mosque with his drawing materials... 'During six weeks, I continued to investigate every part of the mosque and its precincts.' Thus, Catherwood made the first complete survey of the Dome of the Rock, and paved the way for many other artists in subsequent years, such as William Harvey, Ernest Richmond and Carl Friedrich Heinrich Werner.

- ^ "archaeology", Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ Davies, Caroline (19 August 2015). "Khaled al-Asaad profile: the Howard Carter of Palmyra". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ Paraszczuk, Joanna (24 August 2015). "ISIS Killed Khalid al-Assad for Refusing to Betray Palmyra". The Atlantic. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ^ "Centre for Islamic Archaeology". socialsciences.exeter.ac.uk. University of Exeter. Retrieved 2021-12-12.

- ^ a b c Robert Schick, Archaeology and the Quran, Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an

- ^ Quran 26

- ^ Quran 29

- ^ Quran 46

- ^ Jain 2013, p. 121; Kunal 2016, pp. xvi, 135–136; Layton & Thomas 2003, pp. 8–9.

Sources

edit- Jain, Meenakshi (2013). Rama and Ayodhya. New Delhi: Aryan Books. ISBN 978-8173054518.

- Kunal, Kishore (2016). Ayodhya Revisited. Prabhat Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-8430-357-5.

- Layton, Robert; Thomas, Julian (2003). Destruction and Conservation of Cultural Property. Routledge. ISBN 9780748623105.

Further reading

edit- Milwright, Marcus (2010). An Introduction to Islamic Archaeology. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748629954.

- Yılmaz, Halil İbrahim; İzgi, Mahmut Cihat; Erbay, Enes Ensar; Şenel, Samet (2024). "Studying early Islam in the third millennium: a bibliometric analysis". Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 11 (1): Article 1521. doi:10.1057/s41599-024-04058-2.