Egyptian Revival is an architectural style that uses the motifs and imagery of ancient Egypt. It is attributed generally to the public awareness of ancient Egyptian monuments generated by Napoleon's invasion of Egypt in 1798, and Admiral Nelson's defeat of the French Navy at the Battle of the Nile later that year. Napoleon took a scientific expedition with him to Egypt. Publication of the expedition's work, the Description de l'Égypte, began in 1809 and was published as a series through 1826. The size and monumentality of the façades discovered during his adventure cemented the hold of Egyptian aesthetics on the Parisian elite. However, works of art and architecture (such as funerary monuments) in the Egyptian style had been made or built occasionally on the European continent since the time of the Renaissance.

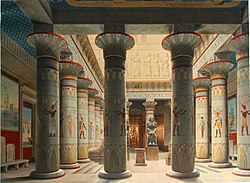

A: The Egyptian Hall in London (1812 destroyed in 1905); B: 1862 lithograph of the Aegyptischer Hof (English: Egyptian court), from the Neues Museum, Berlin (early of mid-19th century); C: Interior of the Temple maçonnique des Amis philanthropes in Brussels, Belgium (1877-1879); D: Egyptian Theatre, Colorado, U.S. (1928) | |

| Years active | Late 18th–present |

|---|---|

History

editEgyptian influence before Napoleon

editMuch of the early knowledge about ancient Egyptian arts and architecture was filtered through the lens of the Classical world, including ancient Rome. Prior to Napoleon's influence an early example is the Obelisk of Domitian, erected in 1651 by Bernini on top of the Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi in Piazza Navona, Rome, which went on to inspire several Egyptian obelisks constructed in Ireland during the early 18th century. It influenced the obelisk constructed as a family funeral memorial by Sir Edward Lovett Pearce for the Allen family at Stillorgan in Ireland in 1717, one of several Egyptian obelisks erected in Ireland during the early 18th century. Others may be found at Belan, County Kildare; and Dangan, County Meath. Conolly's Folly in County Kildare is probably the best known, albeit the least Egyptian-styled.

Egyptian buildings had also been built as garden follies. The most elaborate was probably the one built by Duke Frederick I of Württemberg in the gardens of the Château de Montbéliard. It included an Egyptian bridge across which guests walked to reach an island with an elaborate Egyptian-influenced bath house. Designed by Jean-Baptiste Kléber, later French commander in Egypt, the building had a billiards room and a bagnio.

During the 2nd half of the 18th century, with the rise of Neoclassicism, sometimes architects mixed the Ancient Greek, Roman and Egyptian styles. They wanted to discover new shape and ornament ideas, rather than to be just faithful copyists of the past.[1]

-

Pyramid of Cestius, Rome, by Gaius Cestius, c.12 BC

-

Renaissance monument to Lavinia Thiene, with an Egyptian-inspired pyramid on it, Vicenza Cathedral, Vicenza, Italy, by Giulio Romano, 1544

-

Mural decoration for the Caffè degli Inglesi, Piazza di Spagna, Rome, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, 1769[3]

-

Pyramid in the gardens of Parc Monceau, Paris, unknown architect, 1778

-

Cenotaph in Egyptian Style, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, by Étienne-Louis Boullée, c.1786

-

Cenotaph of Archduchess Maria Christina, Duchess of Teschen, Augustinian Church, Vienna, Austria, by Antonio Canova, 1798–1805[6]

-

Design for the Elysium, by Louis-Sylvestre Gasse, 1799[8]

Napoleonic and Post-Napoleonic eras

editNew after the Napoleonic invasion was a sudden increase of the number of works of art and the fact that, for the first time, entire buildings began to be built to resemble those of ancient Egypt. In France and Britain this was at least partially inspired by successful war campaigns undertaken by each country while in Egypt.

For Napoleon's intention of cataloguing the sights and findings from the campaign, hundreds of artists and scientists were enlisted to document "antiquities, ethnography, architecture, and natural history of Egypt"; and later these notes and sketches were taken back to Europe. In 1803, the compilation of "Description de l'Égypte" was started based on these documents and lasted over twenty years. The content in this archaeological text, includes translation of the Rosetta Stone, pyramids and other scenes, arouse interests in Egyptian arts and culture in Europe and America.

According to James Stevens Curl, people started to present their imaginations about Egypt in various ways. First, combinations of crocodiles, pyramids, mummies, sphinxes, and other motifs were widely circulated. In 1800, an Egyptian opera festival was staged in Drury Lane, London, with Egyptian-themed sets and costumes. On the other hand, William Capon (1757–1827) suggested a massive pyramid for Shooter's Hill as a National Monument, while George Smith (1783–1869) designed an Egyptian-style tomb for Ralph Abercromby in Alexandria.

According to David Brownlee, the 1798 Karlsruhe Synagogue, an early building by the influential Friedrich Weinbrenner was "the first large Egyptian building to be erected since antiquity."[9] According to Diana Muir, it was "the first public building (that is, not a folly, stage set, or funeral monument) in the Egyptian revival style."[10] The ancient Egyptian influence was mainly shown in the two large engaged pylons flanking the entrance; otherwise the windows and entrance of the central section were pointed arches, and the overall plan conventional, with Neo-Gothic details.

Among the earliest monuments of the Egyptian Revival in Paris is the Fontaine du Fellah, built in 1806. It was designed by François-Jean Bralle. A well-documented example, destroyed after Napoleon was deposed, was the monument to General Louis Desaix in the Place des Victoires was built in 1810. It featured a nude statue of the general and an obelisk, both set upon an Egyptian Revival base.[11] Another example of a still standing site of Egyptian Revival is the Egyptian Gate of Tsarskoe Selo, built in 1829.

A street or passage named the Place du Caire or Foire du Caire (Fair of Cairo) was built in Paris in 1798 on the former site of the convent of the "Filles de la Charité". No. 2 Place du Caire, from 1828, is essentially in overall form a conventional Parisian structure with shops on the ground floor and apartments above, but with considerable Egyptianizing decoration including a row of massive Hathor heads and a frieze by sculptor J. G. Garraud.[12]

One of the first British buildings to show an Egyptian Revival interior was the newspaper office of the Courier on the Strand, London. It was built in 1804 and featured a cavetto (coved) cornice and Egyptian-influenced columns with palmiform capitals.[13] Other early British examples include the Egyptian Hall in London, completed in 1812, and the Egyptian Dining Room at Goodwood House (1806). There was also the Egyptian Gallery, a private room in the home of connoisseur Thomas Hope to display his Egyptian antiquities, and illustrated in engravings from his meticulous line drawings in his book Household Furniture (1807), were a prime source for the Regency style of British furnishings.

-

Portico of the Hôtel Beauharnais, Paris, by L.E.N. Bataille, c.1804[14]

-

Fontaine du Fellah, Paris, by François-Jean Bralle, 1806

-

Egyptian room design, unknown location, by Thomas Hope, 1807

-

Sphinx of the Fontaine du Palmier, Paris, unknown sculptor, 1808 and 1858

-

Design for an Egyptian set for Act II of The Magic Flute, by Karl Friedrich Schinkel, 1815, watercolour on paper, Bibliothèque de l'Opéra National, Paris[15]

-

Peter Frederick Robinson's Egyptian Hall (England's Home of Mystery), Wellcome Collection, London, by A. McClatchy after Thomas H. Shepherd, 1828[3]

Rise of Egyptian Revival in America

editThe first Egyptian Revival building in the United States was the 1824 synagogue of Congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia.[16] It was followed by a series of major public buildings in the first half of the 19th century including the 1835 Moyamensing Prison, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States, the 1836 Fourth District Police Station in New Orleans and the 1838 New York City jail known as the Tombs. Other public buildings in Egyptian style included the 1844 Old Whaler's Church in Sag Harbor, New York, the 1846 First Baptist Church of Essex, Connecticut, the 1845 Egyptian Building of the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond and the 1848 United States Custom House (New Orleans). The most notable Egyptian structure in the United States was the Washington Monument, begun in 1848, this obelisk originally featured doors with cavetto cornices and winged sun disks, later removed. The National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri, is another example of Egyptian revival architecture and art.[17]

Around the 1870s, Americans started to become interested in other cultures, including those of Japan, the Middle East and North Africa, leading to a second period of interest in Egyptian revival. Egyptian motifs and symbols were commonly used in the design including elements of "gilt bronze fittings shaped like sphinxes, Egyptian scenes woven into textiles, and geometric renderings of plants such as palm fronds".[18]

Some Americans in the 1880s believed that the United States was a nation without art and therefore wanted to innovate in the field of aesthetic design to distinguish it from Egyptian pyramids and obelisks, Greek temples, and Gothic spires. But implementing such innovations was difficult, and as Clarence King said, "Till there is an American race there cannot be an American style". The creation of the American style was also hindered by the fact that the ethnic mix of the American people did not constitute a race.[19] In the time that followed, however, America's own culture was assimilating Egyptian revivalist architecture, and their tectonic significance became unstable. This may be because the United States of the early 20th century was a confident nation, and the approach of defining one's own spiritual world by establishing a connection to a great civilization like ancient Egypt faded in such a cultural context.[20]

Other countries

editThe South African College in the then-British Cape Colony features an "Egyptian building" constructed in 1841; the Egyptian Revival building of the Cape Town Hebrew Congregation is also still standing.

The York Street Synagogue was Australia's first Egyptian revival building, followed by the Hobart Synagogue, the Launceston Synagogue and the Adelaide Hebrew Congregation, all by 1850. The earliest obelisk in Australia was erected at Macquarie Place, Sydney in 1818.[21]

Later revivals

editThe expeditions that eventually led to the discovery in 1922 of Tutankhamun's tomb by archaeologist Howard Carter resulted in a 20th-century revival. The revival during the 1920s is sometimes considered to be part of the Art Deco style. This phase gave birth to the Egyptian Theatre movement, largely confined to the United States. The Egyptian Revival decorative arts style was present in furniture and other household objects, as well as in architecture.

-

Entrance to Egyptian Avenue of the Highgate Cemetery, London, unknown architect, 19th century[22]

-

Mixed with Neoclassicism – Grave of Louis Poinsot in Père-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, by David d'Angers, mid-19th century

-

Entry gate of the Mount Auburn Cemetery, located on the line between Cambridge and Watertown, Massachusetts, by Jacob Bigelow[23]

-

Egyptian Building, part of the Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, by Thomas Somerville Stewart, 1845[24]

-

Façade of the Masonic Temple of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, by Manuel de Cámara, 1899-1902.

-

Mixed with Art Nouveau – Stained glass window of the Romulus Porescu House, decorated with lotus flowers, Bucharest, Romania, 1905, by Dimitrie Maimarolu[25]

-

Mixed with Art Nouveau – Egyptian House (Rue du Général Rapp no. 10), Strasbourg, France, designed by the architect Franz Scheyder in collaboration with painter Adolf Zilly, 1905–1906[26]

-

Mixed with Romanian Revival and Art Deco – Cenușa Crematory, mixing Egyptian Revival volumes and shapes with other styles, Bucharest, by Duiliu Marcu, 1925–1934

-

Mixed with Art Deco – Grave of Lang-Verte, Père-Lachaise Cemetery, unknown architect, c.1920s

-

Mixed with Art Deco - Elevator door in the Chrysler Building, New York City, by William van Alen, 1929–1930

-

Mixed with Postmodernism – Luxor Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, by Veldon Simpson and Perini Building Company, 1992–1993[30]

Hieroglyphics

editMany notable works in Britain featured attempts by architects to translate and depict messages in Egyptian hieroglyphs.[31] Although sincere attempts at compositions, understanding of hieroglyphic syntax and semantics has advanced since they were built and errors have been discovered in many of these works. Although both public and private buildings were built in Britain in the Egyptian Revival style, the vast majority of those with attempts at accurate inscriptions were public works or on entrances to public buildings.[31]

In 1824, French classical scholar and egyptologist Jean-François Champollion published Precis du systeme hieroglyphique des anciens Egyptiens in 1824, which spurred the first notable attempts to decipher the hieroglyphic language in Britain.[31] Joseph Bonomi the Younger's inscriptions in the entrance lodges to Abney Park Cemetery in 1840 was the first real recorded attempt to compose a legible text. An Egyptologist himself, Bonomi and other scholars such as Samuel Birch, Samuel Sharpe, William Osburne, and others[31] would compose texts for a variety of other British projects throughout the nineteenth century including Marshall's Mill in Leeds, an aedicula in the grounds of Hartwell House, Buckinghamshire, and as part of an Egyptian exhibition in The Crystal Palace after it was re-erected in southeast London.[31]

The content of the inscriptions varied depending on the nature of their specific projects. The Crystal Palace exhibition features several different inscriptions, with the main inscription detailing the construction and content of the hall and proclaiming it as an educational asset to the community. It ends with a message to invoke good fortune, translated as 'let it be prosperous.[31]' Other smaller inscriptions on the cornice of the exhibit entrance feature the names of the builders and a message in Greek wishing for the health and well-being of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert,[31] members of the royal family. The main inscription is accompanied by an English translation, with the characters spaced to match the position of the English words. However, Chris Elliot notes that the translation overly relies on phonetic transliteration and features some unusual characters for words that were difficult to translate into hieroglyphs.[31]

List of buildings

editNorth America

edit- Downtown Presbyterian Church (Nashville), Tennessee; designed by William Strickland from 1849 to 1851

- Washington Monument in Washington, D.C.

- Battle Monument in Baltimore, Maryland

- New Jersey State Penitentiary in Trenton, New Jersey; designed by John Haviland from 1833 to 1836

- Medical College at Richmond in Richmond, Virginia, designed by Thomas Somerville Stewart in 1845

- 1826–1830: Groton Monument in Groton, Connecticut

- 1834–1835: American Institute in New York City

- 1835: Moyamensing Prison in Philadelphia; designed by Thomas Ustick Walter; demolished in 1968

- 1836: 4th Precinct Police Station on Rousseau Street in New Orleans. Designed by Benjamin Buisson, it originally served as a jail and police station. Later altered significantly; now used by the Knights of Babylon krewe for Mardi Gras float storage

- 1838: Green-Wood Cemetery in New York City

- 1838: The Tombs, a court and jail complex in New York City by John Haviland; demolished in 1902

- 1838: Pennsylvania Fire Insurance building in Philadelphia [1] by John Haviland

- 1840: Gates of the Granary Burying Ground, by Isaiah Rogers, in Boston

- 1842: Croton Distributing Reservoir in New York City

- 1827–1843: Bunker Hill Monument in the Charleston neighborhood of Boston

- 1843: Gates and gatehouses of Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts; designed by Jacob Bigelow

- 1844: Old Whaler's Church, Sag Harbor, New York; designed by Minard Lafever

- 1845: The brownstone entry gates of the Grove Street Cemetery, by Henry Austin, New Haven, Connecticut, United States

- 1846: First Baptist Church of Essex, Connecticut

- 1856: Skull and Bones undergraduate secret society at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut (architect's attribution in dispute—may also be Henry Austin of the Grove Street Cemetery gates)

- 1894: The Cairo apartment building in Washington, D.C.

- 1914: Masonic Temple in Charlotte, North Carolina (1914–87)

- 1914–1916: Winona Savings Bank Building in Winona, Minnesota

- 1920: Marmon Hupmobile Showroom in Chicago; designed by Paul Gerhardt

- 1922: Grauman's Egyptian Theatre in Los Angeles

- 1927: Pythian Temple (New York City)

- 1928: Lincoln Theatre (Columbus, Ohio); has an Egyptian revival interior

- 1939: Social Security Administration Building (Washington, DC)

- 1966: Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum in San Jose, California

Europe, Russia, Africa and Australia

edit- 18–12 BC Pyramid of Cestius, Rome

- 1798 Karlsruhe Synagogue

- circa 1820: Donkin Memorial in Port Elizabeth, South Africa

- 1822: Egyptian temple in Łazienki Park in Warsaw, Poland

- 1824: 42 Fore Street in Hertford, known locally as the Egyptian House, is an English Heritage Grade II listed building built on the site of a former inn. A grocery store from the Victorian era until the 1960s, now a restaurant.

- 1825–1826: Egyptian Bridge in St. Petersburg; collapsed on 20 January 1905, but 1955 replacement incorporated sphinxes and several portions of it remains

- 1827–1830: Egyptian Gate of Tsarskoe Selo, St. Petersburg

- 1835–1837: Egyptian House, Penzance, Cornwall. Built by local bookseller John Lavin as a museum, it is still standing.

- 1836–1840: Temple Works, a former flax mill in the industrial district of Holbeck in Leeds, England; built for textile industrialist John Marshall and held the distinction of being the largest single room in the world when it was built

- 1838–1839: The Egyptian Avenue and inner circle of the Lebanon Circle in Highgate Cemetery in London

- 1838–1840: Temple Lodges Abney Park in London Borough of Hackney

- 1844: Launceston Synagogue in Launceston, Tasmania

- 1845: Hobart Synagogue in Hobart, Tasmania

- 1839–1849 Thorvaldsen Museum, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- 1846–1848: Old Synagogue at Canterbury, England

- 1849: Cape Agulhas Lighthouse, the second-oldest lighthouse in South Africa; also called the "Pharos of the South"

- 1856: Egyptian Temple housing elephants at the Antwerp Zoo; designed by Charles Servais

- 1862–1864: Egyptian temple in the park of Stibbert Museum in Florence, Italy

- 1870: The Egyptian Halls in Glasgow; designed by Alexander Thomson

- 1881–1889: Mausoleo Schilizzi in Naples, Italy

- 1891: The Typhonium near Wissant by the Belgian architect Edmond De Vigne

- 1899: Sha'ar Hashamayim Synagogue (Cairo)

- 1902: Masonic Temple of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain

- 1914: Regional Studies Museum in Krasnoyarsk, Russia

- 1919: Mukhtar Museum in Cairo

- 1921: Louxor theater in Paris

- 1922: Collège des Frères d'Heliopolis in Cairo

- 1925: AbdulHamid al-Shawarby Pasha building in Cairo

- 1927: Emulation Hall, Melbourne, Australia

- 1927: Mausoleum of Saad Zaghloul in Cairo

- 1927– 1928: Collins & Parri's Arcadia Works for Carreras, London

- 1924–1929: Lenin's Mausoleum in Moscow; designed by Aleksey Shchusev using elements borrowed from the Pyramid of Djoser

- 1926–1928: Carreras Cigarette Factory in Camden, London

- 1930: foyer of Oliver Percy Bernard's Strand Palace Hotel, London (destr. 1967–8; parts now London, V&A)

- 1932: Ismailia Monuments Museum in Ismailia, Egypt

- 1933: Moussa Dar'i Synagogue in Cairo

- 1934 Pyramid Theatre, Sale, Greater Manchester, UK (formerly a cinema, both independent and Odeon now a Sports Direct)

- 1930–1937: National Museum of Beirut

- 1934: Former Perth Girls' School in Perth, Western Australia, Australia

- 1937: Manly Town Hall in Manly, New South Wales, Australia

- 1942: Faculty of Engineering, Alexandria University campus in Alexandria, Egypt

- 1946: Royal Rest House, Giza Pyramid Complex, Giza, Egypt

- 1961: Cairo Tower in Cairo

- 1974: Unknown Soldier Memorial (Egypt) in Cairo

- Unknown: Lamati Court in Minya, Egypt

Post-Modern variants

edit- 1989: Louvre Pyramid in Paris

- 1991: Pyramid Arena in Memphis, Tennessee

- 1992: Cheesecake Factory[clarification needed]

- 1993: Tama-Re in Eatonton, Georgia; demolished 2005

- 1993: Luxor Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas

- 1995: City Stars Heliopolis in Cairo

- 1996: The Lost World of Reptiles, an exhibit at the Australian Reptile Park, Somersby, New South Wales, Australia

- 1997: Wafi City, Wafi, Dubai City, Dubai UAE

- 1997: Sunway Pyramid, Bandar Sunway, Malaysia.

- 2001: Embassy of the Arab Republic of Egypt in Berlin

- 2001: Supreme Constitutional Court of Egypt building, Cairo

- 2001: Scotiabank Theatre Chinook Centre in Calgary, Alberta

- 2010: Sohag International Airport terminal building in Sohag, Egypt

- 2010: Fairmont Nile City, Cairo

- 2019–present: New Administrative Capital, Egypt, including Iconic Tower (Egypt), Oblisco Capitale, The Octagon (Egypt), Egyptian New Parliament, Presidential Palace and more

- 2022: Cairo Security Directorate, New Cairo, Egypt

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Bergdoll 2000, pp. 23.

- ^ Sund 2019, p. 221.

- ^ a b Sund 2019, p. 210.

- ^ Borngässer, Barbara (2020). Potsdam – Art, Architecture abd Landscape. Vista Point. p. 292. ISBN 978-3-96141-579-3.

- ^ Bergdoll 2000, pp. 113.

- ^ Argan, Giulio Carlo (1982). Art Modernă (in Romanian). Editura Meridiane.

- ^ Valade, Bernard; Fierro, Alfred (1997). Paris (in French). Citadelles & Mazenod. p. 296. ISBN 2-85088-150-3.

- ^ Gössel, Peter; Leuthäuser, Gabriele (2022). Architecture in the 20th Century. Taschen. p. 11. ISBN 978-3-8365-7090-9.

- ^ David Brownlee, Frederich Weinbrenner: Architect of Karlsruhe, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. p. 92.

- ^ Diana Muir Appelbaum, "Jewish Identity and Egyptian Revival Architecture", Journal of Jewish Identities, 2012, 5(2) p. 7.

- ^ Curl, James Stevens (2005). The Egyptian Revival. Psychology Press. p. 276. ISBN 9780415361194.

- ^ James Stevens Curl, The Egyptian Revival, Routledge/* Post-Napoleonic era */ , London, 2005. p. 267.

- ^ Egyptomania: Egypt in Western Art, 1730–1930, Jean-Marcel Humbert, Michael Pantazzi and Christiane Ziegler, 1994, pp. 172–173

- ^ Sund 2019, p. 216.

- ^ Graham-Nixon, Andrew (2023). art THE DEFINITIVE VISUAL HISTORY. DK. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-2416-2903-1.

- ^ Diana Muir, "Jewish Identity and Egyptian Revival Architecture", Journal of Jewish Identities, 2012 5(2)

- ^ "Elements of the Museum and Memorial | National WWI Museum and Memorial". National WWI Museum and Memorial. 2013-03-01. Retrieved 2018-11-02.

- ^ Ickow, Sara (July 2012). "Egyptian Revival". www.metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 2012-11-05. Retrieved 2021-09-30.

- ^ Giguere, Joy M. (2014). Characteristically American : memorial architecture, national identity, and the Egyptian revival (1st ed.). Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-1-62190-077-1. OCLC 893336717.

- ^ Grubiak, Margaret M. (2016). "Characteristically American: Memorial Architecture, National Identity, and the Egyptian Revival by Joy M. Giguere". Technology and Culture. 57 (1): 256–257. doi:10.1353/tech.2016.0009. ISSN 1097-3729. S2CID 112725318.

- ^ Humbert, Jean-Marcel and Price, Clifford, eds., Imhotep Today: Egyptianizing Architecture, UCL Prewss, 2003, pp. 167 ff.

- ^ Sund 2019, p. 222.

- ^ Sund 2019, p. 223.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 130.

- ^ Constantin, Paul (1972). Arta 1900 în România (in Romanian). Editura Meridiane. p. 93.

- ^ Thibaut (26 September 2022). "The Egyptian House Of Strasbourg". enjoystrasbourg.com. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

- ^ Texier, Simon (2022). Architectures Art Déco – Paris et Environs – 100 Bâtiments Remarquable. Parigramme. p. 37. ISBN 978-2-37395-136-3.

- ^ Sund 2019, p. 224.

- ^ van Lemmen, Hans (2013). 5000 Years of Tiles. The British Museum Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-7141-5099-4.

- ^ Sund 2019, p. 212.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Elliot, Chris (2013). "Compositions in Egyptian Hierogylphs in Nineteenth Century England". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 99: 171–189. doi:10.1177/030751331309900108. S2CID 193273948.

References

edit- Bergdoll, Barry (2000). European Architecture 1750–1890. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-284222-0.

- Hopkins, Owen (2014). Architectural Styles: A Visual Guide. Laurence King. ISBN 978-178067-163-5.

- Sund, July (2019). Exotic: A Fetish for the Foreign. Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-7637-5.

External links

edit- Media related to Egyptian Revival architecture at Wikimedia Commons