Fiche Personne

Histoire/société

© GCIS

© GCIS

Thabo Mbeki

Président/e de la République

Afrique du Sud

© GCIS

© GCIS

Français

Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki (né le 18 juin, 1942) est un homme politique sud-africain, président de la République d’Afrique du Sud depuis avril 1999.

Biographie

Originaire de la région du Transkei dans l’actuelle province du Cap-Oriental, Mbeki est le fils de Govan Mbeki (1910-2001), un militant notable du Congrès national africain (ANC) et du Parti communiste sud-africain (SACP).

Sa langue maternelle, ainsi que celle de Nelson Mandela, est le xhosa.

Mbeki a rejoint l’ANC à l’âge de 14 ans, et l’a représenté auprès de gouvernements étrangers à partir de 1967.

Il est nommé chef du département de l’information du parti en 1984 et du département des relations extérieures en 1989.

Avec l’ANC majoritaire à l’assemblée d’Afrique du Sud lors des premières élections multiraciales de 1994, il est avec Frederik de Klerk l’un des deux vice-présidents de Nelson Mandela.

En 1996, à la suite de la démission de Frederik de Klerk et du retrait du Parti national du gouvernement, Thabo Mbeki devient l’unique vice-président d’Afrique du Sud au côté de Nelson Mandela lequel lui délègue l’essentiel de ses pouvoirs exécutifs.

En juin 1999, il est naturellement élu président de la République et succède à Nelson Mandela. Il choisit Jacob Zuma comme vice-président.

Thabo Mbeki a été réélu en avril 2004 avec une majorité parlementaire encore plus étendue qui s’accroît encore par la suite avec la fusion-absorption du Nouveau Parti national.

Dans les affaires internationales, Mbeki a joué un rôle notable dans les mises en ?uvre du Nouveau partenariat pour le développement de l’Afrique et de l’Union africaine. Il a aidé à la promotion des processus de paix au Rwanda, au Burundi et en RDC. Mbeki a également tâché de promulguer le concept de « Renaissance africaine ». Son gouvernement a coopéré avec ceux du Brésil sous la présidence de Lula da Silva et de l’Inde sous le gouvernement d’Atal Bihari Vajpayee, constituant une alliance qui est devenue un protagoniste influent pour les intérêts des pays en voie de développement.

Mbeki a persévéré dans ses efforts à remettre en place le dialogue entre le président zimbabwéen Robert Mugabe et son opposition Mouvement pour le changement démocratique malgré le refus des deux partis. Certains (notamment le gouvernement du Royaume-Uni) ont critiqué cette politique de « diplomatie tranquille », suivant laquelle Mbeki s’est également opposé à la suspension du Zimbabwe de Mugabe du Commonwealth.

Sur le plan intérieur, en dépit de la croissance économique, le chômage prospère et les inégalités sociales s’accentuent. Les critiques politiques se déchainent à mesure que l’autoritarisme du gouvernement s’affirme, tiraillé entre sa propre aile gauche et son aile droite.

En juin 2005, Mbeki limoge son populaire et populiste vice-président englué dans un grave scandale politique.

SIDA

Les vues du président Mbeki sur les causes et le traitement du SIDA ont aussi suscité des controverses. Notamment, il demandé en avril 2000 la création d’un groupe de recherche sur le Sida comprenant des scientifiques orthodoxes ainsi que des scientifiques plus sceptiques qui posent la question du lien de causalité entre le VIH et le SIDA. Thabo Mbeki et son ministre de la Santé, le docteur Manto Tshabalala-Msimang ont fait paraître un document retraçant les discussions qui se sont produites à l’occasion de cette rencontre.

Thabo Mbeki et son gouvernement ont essentiellement posé la question du rapport bénéfice/toxicité de deux substances proposées pour diminuer la transmission de la séropositivité de la mère à l’enfant, qui sont l’ AZT et la Nevirapine, à la suite d’études [1] [2] assez circonstanciées effectuées par l’avocat sud-africain Anthony Brink

Malgré la critique que le gouvernement n’a ?uvré ni assez ni suffisamment vite pour combattre la pandémie qui afflige peut-être 10% de la population du pays, les militants luttant contre le SIDA ont applaudi ce gouvernement lorsqu’il a défendu la production de médicaments génériques moins coûteux par les pays les moins fortunés, et remporté le procès entrepris par des sociétés pharmaceutiques multinationales en avril 2001.

L’Afrique du Sud jouit aujourd’hui d’un projet plus orthodoxe et compréhensif pour combattre les effets du VIH et du SIDA. Son projet de santé est organisé par le docteur Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, ministre de la Santé depuis décembre 2000.

[1] http://www.tig.org.za/pdf-files/debating_azt.pdf

[2] http://www.tig.org.za/pdf-files/poc_a5.pdf

Un article de Wikipédia, l’encyclopédie libre.

Consulté le 12 juillet 2007 à 15h00 GMT

Biographie

Originaire de la région du Transkei dans l’actuelle province du Cap-Oriental, Mbeki est le fils de Govan Mbeki (1910-2001), un militant notable du Congrès national africain (ANC) et du Parti communiste sud-africain (SACP).

Sa langue maternelle, ainsi que celle de Nelson Mandela, est le xhosa.

Mbeki a rejoint l’ANC à l’âge de 14 ans, et l’a représenté auprès de gouvernements étrangers à partir de 1967.

Il est nommé chef du département de l’information du parti en 1984 et du département des relations extérieures en 1989.

Avec l’ANC majoritaire à l’assemblée d’Afrique du Sud lors des premières élections multiraciales de 1994, il est avec Frederik de Klerk l’un des deux vice-présidents de Nelson Mandela.

En 1996, à la suite de la démission de Frederik de Klerk et du retrait du Parti national du gouvernement, Thabo Mbeki devient l’unique vice-président d’Afrique du Sud au côté de Nelson Mandela lequel lui délègue l’essentiel de ses pouvoirs exécutifs.

En juin 1999, il est naturellement élu président de la République et succède à Nelson Mandela. Il choisit Jacob Zuma comme vice-président.

Thabo Mbeki a été réélu en avril 2004 avec une majorité parlementaire encore plus étendue qui s’accroît encore par la suite avec la fusion-absorption du Nouveau Parti national.

Dans les affaires internationales, Mbeki a joué un rôle notable dans les mises en ?uvre du Nouveau partenariat pour le développement de l’Afrique et de l’Union africaine. Il a aidé à la promotion des processus de paix au Rwanda, au Burundi et en RDC. Mbeki a également tâché de promulguer le concept de « Renaissance africaine ». Son gouvernement a coopéré avec ceux du Brésil sous la présidence de Lula da Silva et de l’Inde sous le gouvernement d’Atal Bihari Vajpayee, constituant une alliance qui est devenue un protagoniste influent pour les intérêts des pays en voie de développement.

Mbeki a persévéré dans ses efforts à remettre en place le dialogue entre le président zimbabwéen Robert Mugabe et son opposition Mouvement pour le changement démocratique malgré le refus des deux partis. Certains (notamment le gouvernement du Royaume-Uni) ont critiqué cette politique de « diplomatie tranquille », suivant laquelle Mbeki s’est également opposé à la suspension du Zimbabwe de Mugabe du Commonwealth.

Sur le plan intérieur, en dépit de la croissance économique, le chômage prospère et les inégalités sociales s’accentuent. Les critiques politiques se déchainent à mesure que l’autoritarisme du gouvernement s’affirme, tiraillé entre sa propre aile gauche et son aile droite.

En juin 2005, Mbeki limoge son populaire et populiste vice-président englué dans un grave scandale politique.

SIDA

Les vues du président Mbeki sur les causes et le traitement du SIDA ont aussi suscité des controverses. Notamment, il demandé en avril 2000 la création d’un groupe de recherche sur le Sida comprenant des scientifiques orthodoxes ainsi que des scientifiques plus sceptiques qui posent la question du lien de causalité entre le VIH et le SIDA. Thabo Mbeki et son ministre de la Santé, le docteur Manto Tshabalala-Msimang ont fait paraître un document retraçant les discussions qui se sont produites à l’occasion de cette rencontre.

Thabo Mbeki et son gouvernement ont essentiellement posé la question du rapport bénéfice/toxicité de deux substances proposées pour diminuer la transmission de la séropositivité de la mère à l’enfant, qui sont l’ AZT et la Nevirapine, à la suite d’études [1] [2] assez circonstanciées effectuées par l’avocat sud-africain Anthony Brink

Malgré la critique que le gouvernement n’a ?uvré ni assez ni suffisamment vite pour combattre la pandémie qui afflige peut-être 10% de la population du pays, les militants luttant contre le SIDA ont applaudi ce gouvernement lorsqu’il a défendu la production de médicaments génériques moins coûteux par les pays les moins fortunés, et remporté le procès entrepris par des sociétés pharmaceutiques multinationales en avril 2001.

L’Afrique du Sud jouit aujourd’hui d’un projet plus orthodoxe et compréhensif pour combattre les effets du VIH et du SIDA. Son projet de santé est organisé par le docteur Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, ministre de la Santé depuis décembre 2000.

[1] http://www.tig.org.za/pdf-files/debating_azt.pdf

[2] http://www.tig.org.za/pdf-files/poc_a5.pdf

Un article de Wikipédia, l’encyclopédie libre.

Consulté le 12 juillet 2007 à 15h00 GMT

English

Thabo Mbeki

12th President of South Africa

Born June 18, 1942 (1942-06-18) (age 65)

Idutywa, Eastern Cape

Nationality South African

Political party African National Congress

Spouse Zanele Mbeki

Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki (born June 18, 1942) is the current President of the Republic of South Africa.

* 1 Early years

* 2 Exile and return

* 3 Role in African politics

* 4 Economic policies

* 5 Political style

* 6 Mbeki and the Internet

* 7 Controversies in Zimbabwe

o 7.1 2002 Presidential elections

o 7.2 2005 parliamentary elections

o 7.3 Dialogue between Zanu-PF and MDC

o 7.4 Business response

o 7.5 Rejection of Taking a Tough Line on Mugabe

* 8 Controversies: AIDS

* 9 Debate with Archbishop Tutu

* 10 Mbeki, Zuma, and succession

* 11 See also

* 12 References

* 13 External links

Early years

Born and raised in what is now the Eastern Cape province of South Africa, Mbeki is the son of Govan Mbeki (1910 – 2001), a stalwart of the African National Congress (ANC) and the South African Communist Party. He is a native Xhosa speaker; his parents were both teachers and activists in a rural area of ANC strength, and Mbeki describes himself as « born into the struggle »; a portrait of Karl Marx sat on the family mantlepiece, and a portrait of Mohandas Gandhi was on the wall.[1] He attended high school at Lovedale but was expelled as a result of the student strikes in 1959. He continued his studies at home and wrote his matriculation at St John’s High School in Umtata that same year.

Govan Mbeki had come to the rural Eastern Cape as a political activist after earning two university degrees; he urged his family to make the ANC their family, and of his children, Thabo Mbeki is the one who most clearly followed that instruction, joining the party at age 14 and devoting his life to it thereafter.[2][1] His cousin Phindile Mfeti disappeared without a trace during the apartheid era, and the family to this day does not know what happened to him.[3]

After leaving the Eastern Cape, he lived in Johannesburg, working with Walter Sisulu. After the arrest and imprisonment of Sisulu, Mandela and his father, and facing a similar fate, Thabo Mbeki left South Africa as one of a number of young ANC militants sent abroad to continue their education and their anti-apartheid activities. He ultimately spent 28 years in exile, only returning to his homeland after the release of Nelson Mandela.

Mbeki spent the early years of his exile in the United Kingdom, earning a Master of Economics degree from the University of Sussex and then working in the ANC’s London office on Penton Street. He received military training in what was then the Soviet Union and lived at different times in Botswana, Swaziland and Nigeria, but his primary base was in Lusaka, Zambia, the site of the ANC headquarters.

While in exile, his brother Jama Mbeki was murdered by agents of the Lesotho government in 1982. His son Kwanda-the product of a liaison in Mbeki’s teenage years-was killed while trying to leave South Africa to join his father. When Mbeki finally was able to return home to South Africa and was reunited with his own father, the elder Mbeki told a reporter, « You must remember that Thabo Mbeki is no longer my son. He is my comrade! » A news article pointed out that this was an expression of pride, explaining, « For Govan Mbeki, a son was a mere biological appendage; to be called a comrade, on the other hand, was the highest honour. »[1]

Certainly, Thabo Mbeki devoted his life to the ANC, and during his years in exile was given increasingly responsible roles. Following the 1976 Soweto riots, a student uprising in the township outside Johannesburg, he initiated a regular radio broadcast from Lusaka, tieing ANC followers inside the country to their exiled leaders. Encouraging activists to keep up the pressure on the apartheid regime was a key component in the ANC’s campaign to liberate their country. In the late 1970s Mbeki made a number of trips to the United States in search of support among U.S. corporations. Literate and funny, he made a wide circle of friends in New York City. Mbeki was appointed head of the ANC’s information department in 1984 and then became head of the international department in 1989, reporting directly to Oliver Tambo, then President of the ANC. Tambo was Mbeki’s long-time mentor.

In 1985, Mbeki was a member of a delegation that began meeting secretly with representatives of the South African business community, and in 1989, he led the ANC delegation that conducted secret talks with the South African government. These talks led to the unbanning of the ANC and the release of political prisoners. He also participated in many of the other important discussions between the ANC and the government that eventually led to the democratisation of South Africa.[4]

He became a deputy president of South Africa in May 1994 on the attainment of universal suffrage, and sole deputy-president in June 1996. He succeeded Nelson Mandela as ANC president in December 1997 and as president of the Republic in June 1999 (inaugurated on June 16); he was subsequently reelected for a second term in April 2004.

Role in African politics

Mbeki has been a notably powerful figure in African politics, positioning South Africa as a regional powerbroker and also promoting the idea that African political conflicts should be solved by Africans. He headed the formation of both the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) and the African Union (AU) and has played influential roles in brokering peace deals in Rwanda, Burundi, Ivory Coast and the Democratic Republic of Congo. He has also tried to popularise the concept of an African Renaissance. He sees African dependence on aid and foreign intervention as a major barrier to the continent being taken seriously in the world of economics and politics, and sees structures like NEPAD and the AU as part of a process in which Africa solves its own problems without relying on outside assistance.

Economic policies

Some South African political analysts see a split within the ANC between the « prisoner » generation of leaders, like Nelson Mandela, who studied political theory together in prison, and the « exiles » like Mbeki, who studied economics in Western universities and helped the ANC-in-exile gain credibility with Western nations and corporations. Because Mbeki and his counterparts represented the ANC to the West when ANC’s worked to isolate the apartheid government internationally in the 1980s, they may have been more conscious of the compromises that the ANC would have to make once it gained power.

Few ANC members anticipated the economic shambles of the sanctions-hobbled and high-spending apartheid government. Rather than redistributing an inheritance of white economic power, the ANC was forced into austerity measures and deficit reduction.

To many, Mandela represents the emotional warmth of the older brand of socialist politics of the ANC. But even during Mandela’s presidency and certainly after it, Mbeki and his allies in the government emphasised market-oriented economic approaches. Even beyond the difficulties of inheriting the debts of apartheid, Mbeki appears to believe that economic growth must occur before redistribution. He also emphasised avoidance of debt as a way of maintaining political and economic independence for the new state. Mbeki has emphasised that any policy that would redistribute wealth at the expense of economic growth and deficit reduction would ultimately put the nation into a downward spiral of market shrinkage and debt accumulation. He has pointed to Zimbabwe’s post-liberation direction as an example of the dangers of an overly redistributive approach.

The CIA Factbook says: « South African economic policy is fiscally conservative, but pragmatic, focusing on targeting inflation and liberalising trade as means to increase job growth and household income. »[5]

Like many things in South Africa, this policy choice has difficult racial implications. The ANC must balance to keep its promises to its core constituency, the impoverished black majority, while pleasing the white-dominated businesses who can take their capital elsewhere if the regime is explicitly socialist. Mbeki explains his policies in Africanist terms, and believes deeply in the idea of black empowerment. But he does so by tuning his policies to the constraints of market forces rather than attempting to overturn capitalism’s organising principles, as earlier generations of liberation politicians might have attempted to do.

This policy direction, embodied by the Growth, Employment And Redistribution (GEAR) program, was often unpopular with leftist constituencies inside the ANC and outside it, including ANC-affiliated labor unions within the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the non-party-affiliated « social movements » which have protested Mbeki’s policies on AIDS, land redistribution and service delivery (e.g., the government’s insistence on payment from the poor for utilities like electricity and water).

The more free-market-oriented Democratic Alliance (the largest opposition party) and smaller political groups have sometimes criticised affirmative action efforts such as aspects of Batho pele, for other policies oriented towards redressing apartheid’s inequalities. But the business community inside and outside South Africa has retained faith in the ANC government to a degree that defies many pre-democracy predictions.

Although unemployment remains high and black poverty remains the rule rather than the exception, the economy overall has grown. Perhaps as a result, most South Africans remain loyal to the ANC and to Mbeki’s government, and are willing to see economic transformation and redistribution of wealth as a long process.

Political style

Mbeki has sometimes been characterised as remote and academic, although in his second campaign for Presidency in 2004, many observers described him as finally relaxing into a more traditional campaign mode, sometimes dancing at events and even kissing babies. Yet, the fact that this was remarkable confirms the broader observation that Mbeki values the exercise of centralised policy over demonstrations of grassroots populism.

Mbeki’s thinking can often be found in his weekly column in the ANC newsletter ANC Today,[6] where he often produces discussions on a variety of topics. He sometimes uses his column to deliver pointed invectives against political opponents, and at other times uses it as a kind of professor of political theory, educating ANC cadres on the intellectual justifications for ANC policy. Although these columns are remarkable for their dense prose, they often manage to make news. Recently he denied the existence of rampant crime in the country and blamed the white population for exaggerating the degree to which it exists.[citation needed]Although Mbeki does not generally make a point of befriending or courting reporters, his columns and news events have often yielded good results for his administration by ensuring that his message is a primary driving force of news coverage.[7] Indeed, in initiating his columns, Mbeki stated his view that the bulk of South African media sources did not speak for or to the South African majority, and stated his intent to use ANC Today to speak directly to his constituents rather than through the media.[8]

Mbeki and the Internet

Unlike many world leaders, Mbeki appears to be at ease with the Internet and willing to quote from it. For instance, in a column discussing Hurricane Katrina,[9] he cited Wikipedia, quoted at length a discussion of Katrina’s lessons on American inequality from the Native American publication Indian Country Today,[10] and then included excerpts from a David Brooks column in the New York Times in a discussion of why the events of Katrina illustrated the necessity for global development and redistribution of wealth.

His penchant for quoting diverse and sometimes obscure sources, both from the Internet and from a wide variety of books, makes his column an interesting parallel to political blogs although the ANC does not describe it in these terms. His views on AIDS (see below) were supported by Internet searching which led him to so-called « AIDS dissident » websites; in this case, Mbeki’s use of the Internet was roundly criticised and even ridiculed by opponents.

Controversies in Zimbabwe

Due to South Africa’s proximity, strong trade links, and similar struggle credentials, South Africa is in a unique, and possibly solitary, position to influence politics in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe’s economic slide since 2000 has been a matter of increasing concern to Britain (as the former colonial power) and other donors to that country, and high-ranking diplomatic visits to South Africa have repeatedly attempted to persuade Mbeki to take a harder line with his once-comrade, Robert Mugabe, over takeovers of private farms by groups of Mugabe-allied war veterans, freedom of the press, and independence of the judiciary.

To the West’s concern, Mbeki has never publicly criticised Mugabe’s policies – preferring’quiet diplomacy’ rather than’megaphone diplomacy’, his term for the West’s increasingly forthright condemnation of Mugabe’s rule.

To quote Mbeki – The point really about all this from our perspective has been that the critical role we should play is to assist the Zimbabweans to find each other, really to agree among themselves about the political, economic, social, other solutions that their country needs. We could have stepped aside from that task and then shouted, and that would be the end of our contribution…They would shout back at us and that would be the end of the story. I’m actually the only head of government that I know anywhere in the world who has actually gone to Zimbabwe and spoken publicly very critically of the things that they are doing.

2002 Presidential elections

Mugabe faced a critical presidential election in 2002. The runup was shadowed by a difficult decision to suspend Zimbabwe from the Commonwealth. The full meeting of the Commonwealth had failed in a consensus to decide on the issue, and they tasked the previous, present (at the time), and future leaders of Commonwealth – (respectively President Olusegun Obasanjo of Nigeria, John Howard of Australia, and Mbeki of South Africa) to come to a consensus between them over the issue. On March 20, 2002 (10 days after the elections, which Mugabe won) Howard announced that they had agreed to suspend Zimbabwe for a year.

2005 parliamentary elections

In the face of recent passage of laws restricting public assembly and freedom of the media, muzzling campaigning by the MDC for the 2005 Zimbabwe parliamentary elections, President Mbeki was quoted as saying: I have no reason to think that anything will happen ? that anybody in Zimbabwe will act in a way that will militate against the elections being free and fair. […] As far as I know, things like an independent electoral commission, access to the public media, the absence of violence and intimidation ? those matters have been addressed.

Current deputy-president Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka (Minerals and Energy Minister at that time) led the largest foreign observer mission to oversee the elections. That observer mission congratulated the people of Zimbabwe for holding a peaceful, credible and well-mannered election which reflects the will of the people.

The elections were denounced in the west, who accused Zanu-PF of using food to buy votes, and large discrepancies in the tallying of votes.

Dialogue between Zanu-PF and MDC

Mbeki has been attempting to restore dialogue between Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe and the opposition Movement for Democratic Change in the face of denials from both parties. A fact-finding mission in 2004 by Congress of South African Trade Unions to Zimbabwe led to their widely-publicised deportation back to South Africa which reopened the debate, even within the ANC, as to whether Mbeki’s policy of’quiet diplomacy’ is constructive.

On February 5, 2006 Mbeki said in an interview with SABC television that Zimbabwe had missed a chance to resolve its political crisis in 2004 when secret talks to agree on a new constitution ended in failure. He claimed that he saw a copy of a new constitution signed by all parties.[11] The job of promoting dialogue between the ruling party and the opposition was likely made more difficult by divisions within the MDC, splits to which the president alluded when he stated that the MDC were « sorting themselves out. »[12] In turn, the MDC unanimously rejected this assertion. MDC secretary general Welshman Ncube said « We never gave Mbeki a draft constitution – unless it was ZANU PF which did that. Mbeki has to tell the world what he was really talking about. »[13]

There were reports in May 2007 that Mbeki had been partisan and taken sides with Zanu-PF in his role as mediator. He had given pre-conditions to the opposition Movement for Democratic Change before the dialogue could resume while giving no conditions given to the government side. He has asked that the MDC be required to accept and recognize that Robert Mugabe was the president of Zimbabwe and that he won the 2002 elections[14] despite the fact that they were fraudulent.[15][16][17]

Business response

On January 10, 2006, businessman Warren Clewlow, who serves on the boards of four of the top 10 listed companies in SA, including Old Mutual, Sasol, Nedbank and Barloworld, said that government should stop its unsuccessful behind-the-scenes attempts to resolve the Zimbabwean crisis and start vociferously condemning what was happening in that country. Clewlow’s sentiments, a clear indicator that the private sector is getting increasingly impatient with government’s « quiet diplomacy » policy on Zimbabwe, were echoed by Business Unity SA (Busa), the umbrella body for all business organisations in the country.[18]

As the company’s chairman, he said in Barloworld’s latest annual report that SA’s efforts to date were fruitless and that the only means for a solution was for SA « to lead from the front. Our role and responsibility is not just to promote discussion… Our aim must be to achieve meaningful and sustainable change. »

Rejection of Taking a Tough Line on Mugabe

Mbeki has been criticized for having failed to exert pressure on Mr Mugabe to relinquish power.[19] He rejected calls in May 2007 for tough action against Zimbabwe ahead of a visit by, the then, UK Prime Minister Tony Blair.[20]

Controversies: AIDS

Mbeki’s views on the causes and treatment of AIDS have also been criticised. Most notably in April 2000 he defended a small group of dissident scientists who claim that AIDS is not caused by HIV. His government was applauded by AIDS activists for its successful legal defence against action brought by transnational pharmaceutical companies in April 2001 of a law that would allow cheaper locally-produced medicines. But since then, he and his administration have been repeatedly accused of failing to respond adequately to the epidemic. Current estimates suggest that 5.3 million South Africans have HIV.

AIDS advocates, particularly the Treatment Action Campaign and its allies, campaigned for a program to use anti-retroviral medicines to prevent HIV transmission from mother to child; and then for an overall national treatment program for AIDS that included antiretrovirals. Until 2003, South Africans with HIV who used the public sector health system could get treatment for opportunistic infections they suffered because of their weakened immune systems, but could not get antiretrovirals, designed to specifically target HIV.

In the current South African system, the Cabinet can override the President. Although its votes are private, it appeared to have done so in votes to declare as Cabinet policy that HIV is the cause of AIDS; and then, in August 2003, in a promise to formulate a national treatment plan that would include ARVs. But the Health Ministry is still headed by Dr. Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, who has served as health minister since June 1999, and has promoted nutritional approaches to AIDS while highlighting potential toxicities of antiretroviral drugs. This led critics to question whether the same leadership that opposed ARV treatment would effectively carry out the treatment plan. Indeed, implementation has been slow and activists still criticise Mbeki’s AIDS policies.

It is unclear what led Mbeki to hold unorthodox views of AIDS. While serving as deputy President, AIDS was in his portfolio, and he customarily wore a red ribbon while promoting more conventional views. He did preside over a controversial and brief embrace of a South African experimental drug called Virodene which later proved to be ineffective; the episode appeared to have increased his skepticism about the scientific consensus that quickly condemned the drug.

The largest shift in his views apparently came after he assumed the Presidency. He described AIDS as a « disease of poverty », arguing that political attention should be directed to poverty generally rather than AIDS specifically. Some speculate that the suspicion engendered by a life in exile and by the colonial domination and control of Africa led Mbeki to react against the idea of AIDS as another Western characterisation of Africans as promiscuous and Africa as a continent of disease and hopelessness.[21] For example, speaking to a group of university students in 2001, he struck out against what he viewed as the racism underlying how many in the West characterised AIDS in Africa:

Convinced that we are but natural-born, promiscuous carriers of germs, unique in the world, they proclaim that our continent is doomed to an inevitable mortal end because of our unconquerable devotion to the sin of lust.[22]

Additionally, his views dovetailed with some broader themes in African politics. Many Africans find it suspicious that black Africans bear the largest share of the AIDS burden, and that the drugs to treat it are expensive and sold mainly by Western pharmaceutical companies. The history of malicious and manipulative health policies of the colonial and apartheid governments in Africa, including biological warfare programs set up by the apartheid state, also help to fuel views that the scientific discourse of AIDS might be a tool for European and American political, cultural or economic agendas.

Whatever Mbeki’s views of AIDS are now, ANC rules and his own commitment to the idea of party discipline mean that he cannot publicly criticise the current government policy that HIV causes AIDS and that antiretrovirals should be provided. Some critics of Mbeki assert that his personal views are not in accordance with this policy and still influence AIDS policy behind the scenes, a charge which his office regularly denies.[23]

Debate with Archbishop Tutu

In 2004 the Archbishop Emeritus of Cape Town, Desmond Tutu, criticised President Mbeki for surrounding himself with « yes-men », not doing enough to improve the position of the poor and for promoting economic policies that only benefited a small black elite. He also accused Mbeki and the ANC of suppressing public debate. Mbeki responded that Tutu had never been an ANC member and defended the debates that took place within ANC branches and other public forums. He also asserted his belief in the value of democratic discussion by quoting the Chinese slogan « let a hundred flowers bloom », referring to the brief Hundred Flowers Campaign within the Chinese Communist Party in 1956-57.

The ANC Today newsletter featured several analyses of the debate, written by Mbeki and the ANC.[24][25] The latter suggested that Tutu was an « icon » of « white elites », thereby suggesting that his political importance was overblown by the media; and while the article took pains to say that Tutu had not sought this status, it was described in the press as a particularly pointed and personal critique of Tutu. Tutu responded that he would pray for Mbeki as he had prayed for the officials of the apartheid government.[26]

Mbeki, Zuma, and succession

Mbeki was praised abroad and by some South Africans, but criticised by many ANC members, over his 2005 firing of the deputy president, Jacob Zuma, after Zuma was implicated in a corruption scandal. In October 2005, a few Zuma supporters burned T-shirts portraying Mbeki’s picture at a protest, inspiring condemnation from the ANC leadership. In late 2005, Zuma faced new rape charges, which dimmed his political prospects. But his supporters suggested that there was a Mbeki-led political conspiracy against him. There was visible split between Zuma’s supporters and Mbeki’s allies in the ANC.

Mbeki has been accused of hoping for a constitutional change which would allow a third term in office, but he and other senior ANC members have always denied this. In February 2006, Mbeki told the SABC that he and the ANC have no intention to change the Constitution. He stated, « By the end of the 2009, I will have been in a senior position in government for 15 years. I think that’s too long. »[12] But he has no clear successor within the ANC, and the battle for this position is likely to be intense. The Zuma saga can be seen as an early round of a political drama which has already begun, at the start of Mbeki’s second term.

References

1. ^ a b c Gevisser, Mark (2001). ANC was his family, the struggle was his life. Sunday Times. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

2. ^ Malala, Justice (2004). Mbeki: Born into struggle. BBC. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

3. ^ Mbeki, Thabo (2006). Learning to listen and hear. ANC Today. ANC. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

4. ^ Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki. Polity.org.za. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

5. ^ South Africa. The World Factbook. CIA. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

6. ^ ANC Today. ANC. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

7. ^ Kupe, Tawane (2005). Mbeki’s Media Smarts. The Media Online. Mail&Guardian. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

8. ^ Mbeki, Thabo (2001). Welcome to ANC Today. ANC Today. ANC. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

9. ^ Mbeki, Thabo (2001). The shared pain of New Orleans. ANC Today. ANC. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

10. ^ Indian Country Today. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

11. ^ Zanu PF, MDC drew secret new constitution – Mbeki. New Zimbabwe.com (2006). Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

12. ^ a b Mbeki quashes third-term whispers. Mail&Guardian (2006). Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

13. ^ MDC leaders mystified by Mbeki’s comments. Mail&Guardian (2006). Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

14. ^ Zim talks: Mbeki’must be fair’. News 24 (2006). Retrieved on 2007-05-27.

15. ^ Mugabe’s party wins Zimbabwe election. The Guardian (2006). Retrieved on 2007-05-28.

16. ^ Ignatius, David (2006). Contested Victory. PBS. Retrieved on 2007-05-28.

17. ^ Fearing election defeat, aides said to have inflated vote totals : New doubts cast on Mugabe victory. International Herlad Tribune (2006). Retrieved on 2007-05-28.

18. ^ Clewlow urges new approach on Zimbabwe. Business Day (2007). Retrieved on 2007-05-28.

19. ^ Stanford, Peter (2007). Zimbabweans’must make a stand’. The Telegraph. Retrieved on 2007-05-28.

20. ^ South Africa rejects tough line on Zimbabwe. Reuters (2007). Retrieved on 2007-05-28.

21. ^ Power, Samantha (2003). « The AIDS Rebel ». The New Yorker. Retrieved on 2006-11-23.

22. ^ Schneider, Helen; Fassin, Didier (2002). « Denial and defiance: a socio-political analysis of AIDS in South Africa ». AIDS, Supplement 16 (Supplement 4): S45-S51. Retrieved on 2006-11-23.

23. ^ Deane, Nawaal (2005). Mbeki dismisses Rath. Mail&Guardian. Retrieved on 2006-11-23.

24. ^ Mbeki, Thabo (2005). The Sociology of the Public Discourse in Democratic South Africa / Part I – The Cloud with the Silver Lining. ANC Today. ANC. Retrieved on 2006-11-23.

25. ^ Mbeki, Thabo (2005). The Sociology of the Public Discourse in Democratic South Africa / Part II – Who shall set the national agenda?. ANC Today. ANC. Retrieved on 2006-11-23.

26. ^ Tutu, Mbeki & others (2005). Controversy: Tutu, Mbeki & the freedom to criticise. Centre for Civil Society. Retrieved on 2006-11-23.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

12th President of South Africa

Born June 18, 1942 (1942-06-18) (age 65)

Idutywa, Eastern Cape

Nationality South African

Political party African National Congress

Spouse Zanele Mbeki

Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki (born June 18, 1942) is the current President of the Republic of South Africa.

* 1 Early years

* 2 Exile and return

* 3 Role in African politics

* 4 Economic policies

* 5 Political style

* 6 Mbeki and the Internet

* 7 Controversies in Zimbabwe

o 7.1 2002 Presidential elections

o 7.2 2005 parliamentary elections

o 7.3 Dialogue between Zanu-PF and MDC

o 7.4 Business response

o 7.5 Rejection of Taking a Tough Line on Mugabe

* 8 Controversies: AIDS

* 9 Debate with Archbishop Tutu

* 10 Mbeki, Zuma, and succession

* 11 See also

* 12 References

* 13 External links

Early years

Born and raised in what is now the Eastern Cape province of South Africa, Mbeki is the son of Govan Mbeki (1910 – 2001), a stalwart of the African National Congress (ANC) and the South African Communist Party. He is a native Xhosa speaker; his parents were both teachers and activists in a rural area of ANC strength, and Mbeki describes himself as « born into the struggle »; a portrait of Karl Marx sat on the family mantlepiece, and a portrait of Mohandas Gandhi was on the wall.[1] He attended high school at Lovedale but was expelled as a result of the student strikes in 1959. He continued his studies at home and wrote his matriculation at St John’s High School in Umtata that same year.

Govan Mbeki had come to the rural Eastern Cape as a political activist after earning two university degrees; he urged his family to make the ANC their family, and of his children, Thabo Mbeki is the one who most clearly followed that instruction, joining the party at age 14 and devoting his life to it thereafter.[2][1] His cousin Phindile Mfeti disappeared without a trace during the apartheid era, and the family to this day does not know what happened to him.[3]

After leaving the Eastern Cape, he lived in Johannesburg, working with Walter Sisulu. After the arrest and imprisonment of Sisulu, Mandela and his father, and facing a similar fate, Thabo Mbeki left South Africa as one of a number of young ANC militants sent abroad to continue their education and their anti-apartheid activities. He ultimately spent 28 years in exile, only returning to his homeland after the release of Nelson Mandela.

Mbeki spent the early years of his exile in the United Kingdom, earning a Master of Economics degree from the University of Sussex and then working in the ANC’s London office on Penton Street. He received military training in what was then the Soviet Union and lived at different times in Botswana, Swaziland and Nigeria, but his primary base was in Lusaka, Zambia, the site of the ANC headquarters.

While in exile, his brother Jama Mbeki was murdered by agents of the Lesotho government in 1982. His son Kwanda-the product of a liaison in Mbeki’s teenage years-was killed while trying to leave South Africa to join his father. When Mbeki finally was able to return home to South Africa and was reunited with his own father, the elder Mbeki told a reporter, « You must remember that Thabo Mbeki is no longer my son. He is my comrade! » A news article pointed out that this was an expression of pride, explaining, « For Govan Mbeki, a son was a mere biological appendage; to be called a comrade, on the other hand, was the highest honour. »[1]

Certainly, Thabo Mbeki devoted his life to the ANC, and during his years in exile was given increasingly responsible roles. Following the 1976 Soweto riots, a student uprising in the township outside Johannesburg, he initiated a regular radio broadcast from Lusaka, tieing ANC followers inside the country to their exiled leaders. Encouraging activists to keep up the pressure on the apartheid regime was a key component in the ANC’s campaign to liberate their country. In the late 1970s Mbeki made a number of trips to the United States in search of support among U.S. corporations. Literate and funny, he made a wide circle of friends in New York City. Mbeki was appointed head of the ANC’s information department in 1984 and then became head of the international department in 1989, reporting directly to Oliver Tambo, then President of the ANC. Tambo was Mbeki’s long-time mentor.

In 1985, Mbeki was a member of a delegation that began meeting secretly with representatives of the South African business community, and in 1989, he led the ANC delegation that conducted secret talks with the South African government. These talks led to the unbanning of the ANC and the release of political prisoners. He also participated in many of the other important discussions between the ANC and the government that eventually led to the democratisation of South Africa.[4]

He became a deputy president of South Africa in May 1994 on the attainment of universal suffrage, and sole deputy-president in June 1996. He succeeded Nelson Mandela as ANC president in December 1997 and as president of the Republic in June 1999 (inaugurated on June 16); he was subsequently reelected for a second term in April 2004.

Role in African politics

Mbeki has been a notably powerful figure in African politics, positioning South Africa as a regional powerbroker and also promoting the idea that African political conflicts should be solved by Africans. He headed the formation of both the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) and the African Union (AU) and has played influential roles in brokering peace deals in Rwanda, Burundi, Ivory Coast and the Democratic Republic of Congo. He has also tried to popularise the concept of an African Renaissance. He sees African dependence on aid and foreign intervention as a major barrier to the continent being taken seriously in the world of economics and politics, and sees structures like NEPAD and the AU as part of a process in which Africa solves its own problems without relying on outside assistance.

Economic policies

Some South African political analysts see a split within the ANC between the « prisoner » generation of leaders, like Nelson Mandela, who studied political theory together in prison, and the « exiles » like Mbeki, who studied economics in Western universities and helped the ANC-in-exile gain credibility with Western nations and corporations. Because Mbeki and his counterparts represented the ANC to the West when ANC’s worked to isolate the apartheid government internationally in the 1980s, they may have been more conscious of the compromises that the ANC would have to make once it gained power.

Few ANC members anticipated the economic shambles of the sanctions-hobbled and high-spending apartheid government. Rather than redistributing an inheritance of white economic power, the ANC was forced into austerity measures and deficit reduction.

To many, Mandela represents the emotional warmth of the older brand of socialist politics of the ANC. But even during Mandela’s presidency and certainly after it, Mbeki and his allies in the government emphasised market-oriented economic approaches. Even beyond the difficulties of inheriting the debts of apartheid, Mbeki appears to believe that economic growth must occur before redistribution. He also emphasised avoidance of debt as a way of maintaining political and economic independence for the new state. Mbeki has emphasised that any policy that would redistribute wealth at the expense of economic growth and deficit reduction would ultimately put the nation into a downward spiral of market shrinkage and debt accumulation. He has pointed to Zimbabwe’s post-liberation direction as an example of the dangers of an overly redistributive approach.

The CIA Factbook says: « South African economic policy is fiscally conservative, but pragmatic, focusing on targeting inflation and liberalising trade as means to increase job growth and household income. »[5]

Like many things in South Africa, this policy choice has difficult racial implications. The ANC must balance to keep its promises to its core constituency, the impoverished black majority, while pleasing the white-dominated businesses who can take their capital elsewhere if the regime is explicitly socialist. Mbeki explains his policies in Africanist terms, and believes deeply in the idea of black empowerment. But he does so by tuning his policies to the constraints of market forces rather than attempting to overturn capitalism’s organising principles, as earlier generations of liberation politicians might have attempted to do.

This policy direction, embodied by the Growth, Employment And Redistribution (GEAR) program, was often unpopular with leftist constituencies inside the ANC and outside it, including ANC-affiliated labor unions within the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the non-party-affiliated « social movements » which have protested Mbeki’s policies on AIDS, land redistribution and service delivery (e.g., the government’s insistence on payment from the poor for utilities like electricity and water).

The more free-market-oriented Democratic Alliance (the largest opposition party) and smaller political groups have sometimes criticised affirmative action efforts such as aspects of Batho pele, for other policies oriented towards redressing apartheid’s inequalities. But the business community inside and outside South Africa has retained faith in the ANC government to a degree that defies many pre-democracy predictions.

Although unemployment remains high and black poverty remains the rule rather than the exception, the economy overall has grown. Perhaps as a result, most South Africans remain loyal to the ANC and to Mbeki’s government, and are willing to see economic transformation and redistribution of wealth as a long process.

Political style

Mbeki has sometimes been characterised as remote and academic, although in his second campaign for Presidency in 2004, many observers described him as finally relaxing into a more traditional campaign mode, sometimes dancing at events and even kissing babies. Yet, the fact that this was remarkable confirms the broader observation that Mbeki values the exercise of centralised policy over demonstrations of grassroots populism.

Mbeki’s thinking can often be found in his weekly column in the ANC newsletter ANC Today,[6] where he often produces discussions on a variety of topics. He sometimes uses his column to deliver pointed invectives against political opponents, and at other times uses it as a kind of professor of political theory, educating ANC cadres on the intellectual justifications for ANC policy. Although these columns are remarkable for their dense prose, they often manage to make news. Recently he denied the existence of rampant crime in the country and blamed the white population for exaggerating the degree to which it exists.[citation needed]Although Mbeki does not generally make a point of befriending or courting reporters, his columns and news events have often yielded good results for his administration by ensuring that his message is a primary driving force of news coverage.[7] Indeed, in initiating his columns, Mbeki stated his view that the bulk of South African media sources did not speak for or to the South African majority, and stated his intent to use ANC Today to speak directly to his constituents rather than through the media.[8]

Mbeki and the Internet

Unlike many world leaders, Mbeki appears to be at ease with the Internet and willing to quote from it. For instance, in a column discussing Hurricane Katrina,[9] he cited Wikipedia, quoted at length a discussion of Katrina’s lessons on American inequality from the Native American publication Indian Country Today,[10] and then included excerpts from a David Brooks column in the New York Times in a discussion of why the events of Katrina illustrated the necessity for global development and redistribution of wealth.

His penchant for quoting diverse and sometimes obscure sources, both from the Internet and from a wide variety of books, makes his column an interesting parallel to political blogs although the ANC does not describe it in these terms. His views on AIDS (see below) were supported by Internet searching which led him to so-called « AIDS dissident » websites; in this case, Mbeki’s use of the Internet was roundly criticised and even ridiculed by opponents.

Controversies in Zimbabwe

Due to South Africa’s proximity, strong trade links, and similar struggle credentials, South Africa is in a unique, and possibly solitary, position to influence politics in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe’s economic slide since 2000 has been a matter of increasing concern to Britain (as the former colonial power) and other donors to that country, and high-ranking diplomatic visits to South Africa have repeatedly attempted to persuade Mbeki to take a harder line with his once-comrade, Robert Mugabe, over takeovers of private farms by groups of Mugabe-allied war veterans, freedom of the press, and independence of the judiciary.

To the West’s concern, Mbeki has never publicly criticised Mugabe’s policies – preferring’quiet diplomacy’ rather than’megaphone diplomacy’, his term for the West’s increasingly forthright condemnation of Mugabe’s rule.

To quote Mbeki – The point really about all this from our perspective has been that the critical role we should play is to assist the Zimbabweans to find each other, really to agree among themselves about the political, economic, social, other solutions that their country needs. We could have stepped aside from that task and then shouted, and that would be the end of our contribution…They would shout back at us and that would be the end of the story. I’m actually the only head of government that I know anywhere in the world who has actually gone to Zimbabwe and spoken publicly very critically of the things that they are doing.

2002 Presidential elections

Mugabe faced a critical presidential election in 2002. The runup was shadowed by a difficult decision to suspend Zimbabwe from the Commonwealth. The full meeting of the Commonwealth had failed in a consensus to decide on the issue, and they tasked the previous, present (at the time), and future leaders of Commonwealth – (respectively President Olusegun Obasanjo of Nigeria, John Howard of Australia, and Mbeki of South Africa) to come to a consensus between them over the issue. On March 20, 2002 (10 days after the elections, which Mugabe won) Howard announced that they had agreed to suspend Zimbabwe for a year.

2005 parliamentary elections

In the face of recent passage of laws restricting public assembly and freedom of the media, muzzling campaigning by the MDC for the 2005 Zimbabwe parliamentary elections, President Mbeki was quoted as saying: I have no reason to think that anything will happen ? that anybody in Zimbabwe will act in a way that will militate against the elections being free and fair. […] As far as I know, things like an independent electoral commission, access to the public media, the absence of violence and intimidation ? those matters have been addressed.

Current deputy-president Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka (Minerals and Energy Minister at that time) led the largest foreign observer mission to oversee the elections. That observer mission congratulated the people of Zimbabwe for holding a peaceful, credible and well-mannered election which reflects the will of the people.

The elections were denounced in the west, who accused Zanu-PF of using food to buy votes, and large discrepancies in the tallying of votes.

Dialogue between Zanu-PF and MDC

Mbeki has been attempting to restore dialogue between Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe and the opposition Movement for Democratic Change in the face of denials from both parties. A fact-finding mission in 2004 by Congress of South African Trade Unions to Zimbabwe led to their widely-publicised deportation back to South Africa which reopened the debate, even within the ANC, as to whether Mbeki’s policy of’quiet diplomacy’ is constructive.

On February 5, 2006 Mbeki said in an interview with SABC television that Zimbabwe had missed a chance to resolve its political crisis in 2004 when secret talks to agree on a new constitution ended in failure. He claimed that he saw a copy of a new constitution signed by all parties.[11] The job of promoting dialogue between the ruling party and the opposition was likely made more difficult by divisions within the MDC, splits to which the president alluded when he stated that the MDC were « sorting themselves out. »[12] In turn, the MDC unanimously rejected this assertion. MDC secretary general Welshman Ncube said « We never gave Mbeki a draft constitution – unless it was ZANU PF which did that. Mbeki has to tell the world what he was really talking about. »[13]

There were reports in May 2007 that Mbeki had been partisan and taken sides with Zanu-PF in his role as mediator. He had given pre-conditions to the opposition Movement for Democratic Change before the dialogue could resume while giving no conditions given to the government side. He has asked that the MDC be required to accept and recognize that Robert Mugabe was the president of Zimbabwe and that he won the 2002 elections[14] despite the fact that they were fraudulent.[15][16][17]

Business response

On January 10, 2006, businessman Warren Clewlow, who serves on the boards of four of the top 10 listed companies in SA, including Old Mutual, Sasol, Nedbank and Barloworld, said that government should stop its unsuccessful behind-the-scenes attempts to resolve the Zimbabwean crisis and start vociferously condemning what was happening in that country. Clewlow’s sentiments, a clear indicator that the private sector is getting increasingly impatient with government’s « quiet diplomacy » policy on Zimbabwe, were echoed by Business Unity SA (Busa), the umbrella body for all business organisations in the country.[18]

As the company’s chairman, he said in Barloworld’s latest annual report that SA’s efforts to date were fruitless and that the only means for a solution was for SA « to lead from the front. Our role and responsibility is not just to promote discussion… Our aim must be to achieve meaningful and sustainable change. »

Rejection of Taking a Tough Line on Mugabe

Mbeki has been criticized for having failed to exert pressure on Mr Mugabe to relinquish power.[19] He rejected calls in May 2007 for tough action against Zimbabwe ahead of a visit by, the then, UK Prime Minister Tony Blair.[20]

Controversies: AIDS

Mbeki’s views on the causes and treatment of AIDS have also been criticised. Most notably in April 2000 he defended a small group of dissident scientists who claim that AIDS is not caused by HIV. His government was applauded by AIDS activists for its successful legal defence against action brought by transnational pharmaceutical companies in April 2001 of a law that would allow cheaper locally-produced medicines. But since then, he and his administration have been repeatedly accused of failing to respond adequately to the epidemic. Current estimates suggest that 5.3 million South Africans have HIV.

AIDS advocates, particularly the Treatment Action Campaign and its allies, campaigned for a program to use anti-retroviral medicines to prevent HIV transmission from mother to child; and then for an overall national treatment program for AIDS that included antiretrovirals. Until 2003, South Africans with HIV who used the public sector health system could get treatment for opportunistic infections they suffered because of their weakened immune systems, but could not get antiretrovirals, designed to specifically target HIV.

In the current South African system, the Cabinet can override the President. Although its votes are private, it appeared to have done so in votes to declare as Cabinet policy that HIV is the cause of AIDS; and then, in August 2003, in a promise to formulate a national treatment plan that would include ARVs. But the Health Ministry is still headed by Dr. Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, who has served as health minister since June 1999, and has promoted nutritional approaches to AIDS while highlighting potential toxicities of antiretroviral drugs. This led critics to question whether the same leadership that opposed ARV treatment would effectively carry out the treatment plan. Indeed, implementation has been slow and activists still criticise Mbeki’s AIDS policies.

It is unclear what led Mbeki to hold unorthodox views of AIDS. While serving as deputy President, AIDS was in his portfolio, and he customarily wore a red ribbon while promoting more conventional views. He did preside over a controversial and brief embrace of a South African experimental drug called Virodene which later proved to be ineffective; the episode appeared to have increased his skepticism about the scientific consensus that quickly condemned the drug.

The largest shift in his views apparently came after he assumed the Presidency. He described AIDS as a « disease of poverty », arguing that political attention should be directed to poverty generally rather than AIDS specifically. Some speculate that the suspicion engendered by a life in exile and by the colonial domination and control of Africa led Mbeki to react against the idea of AIDS as another Western characterisation of Africans as promiscuous and Africa as a continent of disease and hopelessness.[21] For example, speaking to a group of university students in 2001, he struck out against what he viewed as the racism underlying how many in the West characterised AIDS in Africa:

Convinced that we are but natural-born, promiscuous carriers of germs, unique in the world, they proclaim that our continent is doomed to an inevitable mortal end because of our unconquerable devotion to the sin of lust.[22]

Additionally, his views dovetailed with some broader themes in African politics. Many Africans find it suspicious that black Africans bear the largest share of the AIDS burden, and that the drugs to treat it are expensive and sold mainly by Western pharmaceutical companies. The history of malicious and manipulative health policies of the colonial and apartheid governments in Africa, including biological warfare programs set up by the apartheid state, also help to fuel views that the scientific discourse of AIDS might be a tool for European and American political, cultural or economic agendas.

Whatever Mbeki’s views of AIDS are now, ANC rules and his own commitment to the idea of party discipline mean that he cannot publicly criticise the current government policy that HIV causes AIDS and that antiretrovirals should be provided. Some critics of Mbeki assert that his personal views are not in accordance with this policy and still influence AIDS policy behind the scenes, a charge which his office regularly denies.[23]

Debate with Archbishop Tutu

In 2004 the Archbishop Emeritus of Cape Town, Desmond Tutu, criticised President Mbeki for surrounding himself with « yes-men », not doing enough to improve the position of the poor and for promoting economic policies that only benefited a small black elite. He also accused Mbeki and the ANC of suppressing public debate. Mbeki responded that Tutu had never been an ANC member and defended the debates that took place within ANC branches and other public forums. He also asserted his belief in the value of democratic discussion by quoting the Chinese slogan « let a hundred flowers bloom », referring to the brief Hundred Flowers Campaign within the Chinese Communist Party in 1956-57.

The ANC Today newsletter featured several analyses of the debate, written by Mbeki and the ANC.[24][25] The latter suggested that Tutu was an « icon » of « white elites », thereby suggesting that his political importance was overblown by the media; and while the article took pains to say that Tutu had not sought this status, it was described in the press as a particularly pointed and personal critique of Tutu. Tutu responded that he would pray for Mbeki as he had prayed for the officials of the apartheid government.[26]

Mbeki, Zuma, and succession

Mbeki was praised abroad and by some South Africans, but criticised by many ANC members, over his 2005 firing of the deputy president, Jacob Zuma, after Zuma was implicated in a corruption scandal. In October 2005, a few Zuma supporters burned T-shirts portraying Mbeki’s picture at a protest, inspiring condemnation from the ANC leadership. In late 2005, Zuma faced new rape charges, which dimmed his political prospects. But his supporters suggested that there was a Mbeki-led political conspiracy against him. There was visible split between Zuma’s supporters and Mbeki’s allies in the ANC.

Mbeki has been accused of hoping for a constitutional change which would allow a third term in office, but he and other senior ANC members have always denied this. In February 2006, Mbeki told the SABC that he and the ANC have no intention to change the Constitution. He stated, « By the end of the 2009, I will have been in a senior position in government for 15 years. I think that’s too long. »[12] But he has no clear successor within the ANC, and the battle for this position is likely to be intense. The Zuma saga can be seen as an early round of a political drama which has already begun, at the start of Mbeki’s second term.

References

1. ^ a b c Gevisser, Mark (2001). ANC was his family, the struggle was his life. Sunday Times. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

2. ^ Malala, Justice (2004). Mbeki: Born into struggle. BBC. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

3. ^ Mbeki, Thabo (2006). Learning to listen and hear. ANC Today. ANC. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

4. ^ Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki. Polity.org.za. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

5. ^ South Africa. The World Factbook. CIA. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

6. ^ ANC Today. ANC. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

7. ^ Kupe, Tawane (2005). Mbeki’s Media Smarts. The Media Online. Mail&Guardian. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

8. ^ Mbeki, Thabo (2001). Welcome to ANC Today. ANC Today. ANC. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

9. ^ Mbeki, Thabo (2001). The shared pain of New Orleans. ANC Today. ANC. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

10. ^ Indian Country Today. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

11. ^ Zanu PF, MDC drew secret new constitution – Mbeki. New Zimbabwe.com (2006). Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

12. ^ a b Mbeki quashes third-term whispers. Mail&Guardian (2006). Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

13. ^ MDC leaders mystified by Mbeki’s comments. Mail&Guardian (2006). Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

14. ^ Zim talks: Mbeki’must be fair’. News 24 (2006). Retrieved on 2007-05-27.

15. ^ Mugabe’s party wins Zimbabwe election. The Guardian (2006). Retrieved on 2007-05-28.

16. ^ Ignatius, David (2006). Contested Victory. PBS. Retrieved on 2007-05-28.

17. ^ Fearing election defeat, aides said to have inflated vote totals : New doubts cast on Mugabe victory. International Herlad Tribune (2006). Retrieved on 2007-05-28.

18. ^ Clewlow urges new approach on Zimbabwe. Business Day (2007). Retrieved on 2007-05-28.

19. ^ Stanford, Peter (2007). Zimbabweans’must make a stand’. The Telegraph. Retrieved on 2007-05-28.

20. ^ South Africa rejects tough line on Zimbabwe. Reuters (2007). Retrieved on 2007-05-28.

21. ^ Power, Samantha (2003). « The AIDS Rebel ». The New Yorker. Retrieved on 2006-11-23.

22. ^ Schneider, Helen; Fassin, Didier (2002). « Denial and defiance: a socio-political analysis of AIDS in South Africa ». AIDS, Supplement 16 (Supplement 4): S45-S51. Retrieved on 2006-11-23.

23. ^ Deane, Nawaal (2005). Mbeki dismisses Rath. Mail&Guardian. Retrieved on 2006-11-23.

24. ^ Mbeki, Thabo (2005). The Sociology of the Public Discourse in Democratic South Africa / Part I – The Cloud with the Silver Lining. ANC Today. ANC. Retrieved on 2006-11-23.

25. ^ Mbeki, Thabo (2005). The Sociology of the Public Discourse in Democratic South Africa / Part II – Who shall set the national agenda?. ANC Today. ANC. Retrieved on 2006-11-23.

26. ^ Tutu, Mbeki & others (2005). Controversy: Tutu, Mbeki & the freedom to criticise. Centre for Civil Society. Retrieved on 2006-11-23.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Films(s)

-

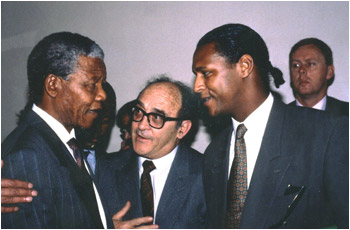

Plot for PeaceLong-métrage – 2013L’histoire secrète de la fin de l’Apartheid Plot for Peace dévoile l’histoire du « complot » ayant conduit à la libération de Nelson Mandela. Pour la première fois, des chefs d’État, des généraux, des diplomates et des …Thabo Mbeki est lié(e) à ce film en tant que acteur/trice

Plot for PeaceLong-métrage – 2013L’histoire secrète de la fin de l’Apartheid Plot for Peace dévoile l’histoire du « complot » ayant conduit à la libération de Nelson Mandela. Pour la première fois, des chefs d’État, des généraux, des diplomates et des …Thabo Mbeki est lié(e) à ce film en tant que acteur/trice -

Comrade GoldbergMoyen-métrage – 2010Réalisateur : Peter Heller Pays de production : Allemagne Pays de tournage : Afrique du SudThabo Mbeki est lié(e) à ce film en tant que acteur/trice

Comrade GoldbergMoyen-métrage – 2010Réalisateur : Peter Heller Pays de production : Allemagne Pays de tournage : Afrique du SudThabo Mbeki est lié(e) à ce film en tant que acteur/trice -

Behind the rainbow (Le pouvoir détruit -il le rêve ?)Long-métrage – 2009Behind the Rainbow met en lumière la transition de l’ANC, le mouvement de libération et au parti du pouvoir de l’Afrique du Sud, à travers l’évolution des relations entre deux de ses plus grands cadres : Thabo Mbeki et J…Thabo Mbeki est lié(e) à ce film en tant que acteur/trice

Behind the rainbow (Le pouvoir détruit -il le rêve ?)Long-métrage – 2009Behind the Rainbow met en lumière la transition de l’ANC, le mouvement de libération et au parti du pouvoir de l’Afrique du Sud, à travers l’évolution des relations entre deux de ses plus grands cadres : Thabo Mbeki et J…Thabo Mbeki est lié(e) à ce film en tant que acteur/trice

Partager :